BEIJING, (Reuters) – When one of your big oil suppliers splits into rival states, that’s a problem for any country. When you’re China, with its huge appetite for energy and a tradition of never wanting to take sides, it becomes a foreign policy migraine.

China’s balancing act between South Sudan and Sudan will take centre stage when the South’s president visits Beijing today, seeking political and economic backing amid escalating tensions with its northern neighbour.

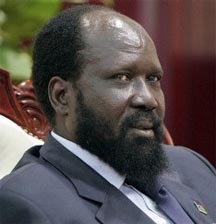

President Salva Kiir’s six-day trip comes days after he ordered troops to withdraw from the oil-rich Heglig region after seizing it from Sudan, a move that brought the two countries to the brink of all-out war.

For China, invested in the oil sector of both nations, the standoff shows how its economic expansion abroad has at times forced Beijing to deal with distant quarrels it would like to avoid. South Sudan gained independence from Khartoum last year.

“We’ve seen Beijing drawn into a tug-of-war, as each side attempts to pull Chinese interests in line with its own,” said Zach Vertin, senior analyst for Sudan and South Sudan at the International Crisis Group think-tank.

“But China doesn’t want to step too far in either direction and risk damaging relations with either of its partners.”

That, Vertin said, is the reality China has to grapple with as its global footprint grows.

Earlier this year, rebel forces in Sudan kidnapped 29 Chinese workers. South Sudan also expelled Liu Yingcai, the head of Petrodar, a largely Chinese-led oil consortium that is the main oil firm operating in the new African nation.

South Sudan said the firm was not fully cooperating with its investigation of oil firms suspected of helping Sudan seize southern oil transported from the landlocked South through Sudan for export.

South Sudan seceded peacefully last year under the terms of a 2005 pact after decades of civil war, gaining control of three-quarters of Khartoum’s oil output.

China’s long-term support for Khartoum, including its role as an arms supplier, had been a sore point with the South. But Beijing has expanded ties with South Sudan, eager to tap its oil. China can also build badly needed infrastructure in the country.

That has placed China between the two hostile nations, but also given it a stake in preserving stability.

“This trip could come at a fortunate time, if China is able to bring some of its influence on the South and push for peace. China can say to Kiir, if no peace, then no development,” said Li Xinfeng, a researcher of African affairs at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

CHINA IN THE MIDDLE

China recognises its clout in both countries puts it in a unique position, but is hesitant to see itself as the key mediator, said Li Weijian, who studies China’s foreign policy at the Shanghai Institutes of International Studies.

“It (South Sudan) wants China to use that influence to help. China will definitely put forth efforts, but this is a long-term dispute and it won’t be resolved simply as a function of China’s involvement,” Li said.