We reprint the following article on Philip Moore by Dr Rupert Roopnaraine that was originally commissioned by Nicholas Laughlin and appeared in Caribbean Beat in 1996.

I interrupted him again this morning. He was at work in a makeshift studio on the ground-floor of a busy complex in central Georgetown, putting the final touches to the Bridge of the Diaspora, one of three new paintings he is to exhibit as an Invited Artist at the upcoming Santo Domingo Bienale. I was on my way to Castellani House, formerly the Residence of the late President Burnham and now the home of Guyana’s National Collection. I have been working there over the last few days, trying to think and feel my way into a few of the 140-odd pieces of his work held by the Collection.

I was due at Castellani House at ten and I was running late. I suggested that we meet there later and continue our conversation. Conversations with him never end, they are broken off. I wanted us to spend some time around the pieces, look at those in storage, talk about Jumbie Wedding and Hurricane Flora. In the attic where I am working, Survival City, overhung with its protective chandelier of calabashes and bells, is two rooms away, down a short corridor, dominating the space and everything around it. Behind me, from the Southern window, a clear, unaccustomed view of his masterful and controversial 1763 Monument.

He agreed to come over. Transportation might be a problem. He spoke, distractedly at first, of the everyday pressures – the hotel bill which had to be settled to avoid embarrassment, the cost of staying alive, the price of a coconut, a mango. “In the Corentyne, we pick coconut and mango, not buy them.” He would have to sell off another painting. Then, without transition, a leap: “What I’ve done, I’ve done a lot. And not just paint for the sake of painting, but paint that the colours will work and be like a psychic force to stimulate that creative subconscious energy in man. Many times I tell these people who belong to these black organisations that they talk about their African man and African drum, but their subconscious mind is the talking drums within them and they can use their word and their creative imagination and re-educate themselves and become the thing that they want to be.” All the while, he went on applying thick dots of bright red paint directly from the tube on to the intricately and densely detailed section of the sky over the Bridge of the Diaspora, the fourth of the glorious bridges Philip Moore has painted over the years.

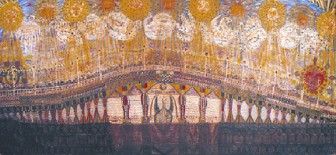

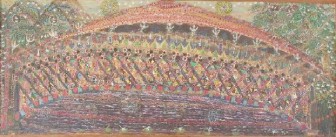

Immediately on entering Castellani House, you are greeted by two of his grand and powerful works of 1978, a painting, Canje Bridge, and a woodcarving, Stool of Resistance. Labour and resistance: the story of Guyana and of more than Guyana. Not even the narrow space across which you must view it can dim the splendour of this spanking new bridge across the Canje River. Streams of light flow from a single sun multiplied into many suns, rhythmically, a drum-beat of visual rhymes and repetitions. “That is an aspect of African art because the rhythmic, monotonous beating of the drums sends some sensations in your mind.” White and fluffy bird-clouds hover above. On the bridge a stream of humanity, crossing and mingling. It is the day to celebrate the opening of the bridge, a Corentyne Sunday. Officialdom must have been in attendance, although there is no sign of them. Instead, hundreds of faces of ordinary people massing on their bridge, walking over water. “United Americas” is written in words above the bridge’s centre: “American money and Guyanese labour,” he explains. To represent navigation, a bird swims under. In the foreground, the greenheart piles driven deep into the earth, ending in the beds of peas and corn and the simple growing things it took to nourish those who laboured on the bridge across the Canje river.

Even now, more than twenty years later, this child of the Corentyne swells with pride as he remembers: “The phenomenal thing was there was an estimation of two years but the people on the Corentyne were so agile in physical labour and construction that they finished that bridge nine months ahead of time.”

Philip Alphonso Moore, the Immanuel Kweku Moorji, was born on October 12, 1921 in Manchester Village on the Corentyne Coast of Guyana. He attended Manchester Church of Scotland School, earning his school-leaving Certificate in 1938. it was to be the end of his formal education. Thirty-two years later he would be appointed Artist in Residence and tutor in wood sculpture at Princeton University. “A self-trained artist can be spirit taught. What I do practically know is that a man can re-educate his subconscious and the subconscious mind can come back and make his conscious mind super-conscious. And we can get any amount of knowledge that we want through this personal self-induction because, if all the elements of technology came out from the mind of man, the mind of man can develop to re-educate man to release the ninety percent of brain power that is dormant.” Education he understands as the drawing out of what is inside, of what we have brought with us from the spirit world. Through meditation we can reach down into the depth of self and find there the strength and genius of the ancestral. This inward seeking was a necessary line of defense for the children of enslavement and indenture growing up in a British colony. “In most cases they wanted to show us that we were born in sin and shaped in iniquity and that we were grandsons and daughters of slaves and that therefore nothing good could come out of us. But with the individual spiritual realisation man comes into the true order of being. That is the basic element of what we call positive revolution. What you have to understand is that apart from your environment and your educational qualification, you have something within you that you have brought from the spirit world and that thing is a part of God.”

For someone who does not hold formal academic education in particularly high esteem, not least because of the conduct of the academically educated, he recalls with pride the day Mr. Francis Williams, a first assistant teacher, gathered the students from the fourth to sixth standard to listen to “this untrained self-taught artist.” He spoke of art and God: “When God said from the sweat of thy brow thou shalt eat bread, that was not all that he said. He said too that by the meditation of your hearts you can be in attunement with me and by the craftiness of your minds you will make gardens even better than Eden. Those words are not a threat to man. Those words became what we call a consolation to man and man became a co-creator with God to make things for his own happiness.” He went on to tell them of his practical experience with painting and carving and spoke to them of the ordinary tings around them. “When I finished talking to them, the teacher called on the students to give three cheers for Mr. Moore. That day was one of the happiest days in my life.” Years later, as a guest speaker at the graduation exercises of the Theological Seminary at Princeton, he was to be touched by the attentiveness and reverence of the students who, only the day before, had been treated to a lecture by someone so learned that his academic qualifications “took half an hour to read out.” And he, an unlettered man from a village with a School Leaving Certificate.

He underwent a mystical conversion at the foot of the Northern stairway of a luminous house in the sky and, in 1941, received his Grand Master initiation and training in the Jordanite religion which he continues to serve as a respected elder. Religion has been from the beginning and remains to this day a well-spring of his art. Before he carved his first head that day in a tent of cane trash in a Skeldon cane-field more than fifty years ago, he had had a dream in which a black hand holding a gouge reached down from a golden cloud and sent him forth to carve and make art. He has gone on making art these fifty years, prodigiously, power objects of beauty for our spiritual renovation, art that is a consolation for man as a co-creator with God. “When I carved up to a certain point, I felt that when I was holding a piece of wood in my hand, it seemed to me that I was holding the mind of the world in my hand.”

Recognition was slow in coming. The Georgetown pioneers, steeping themselves in the European tradition, were centred around the legendary E. R. Burrowes and grouped in his Working People’s Art Class. They seem to have regarded the untutored country boy Moore as an oddity, although Burrowes would complement him on his great sense of proportion. He recalls with a great gale of laughter Mr. Moshett inviting other members of the Art Class to express their thanks to Mr. Moore for “bringing so much lumber from Corentyne.” It is easy to imagine the polite consternation this African elephant from the Corentyne must have provoked in the china shop of the Georgetown art elite. Years later, on his death bed in Mercy Hospital, Burrowes was to say to him: “Philip, I’m going to die and leave art for you younger people. One day you will make Guyana famous.”

One of the most remarkable pieces of that Corentyne lumber, Bat and Ball Fantasy, carved in 1968, brought him his first international recognition. He had sent up photographs of the Fantasy and Symphony of Life as entries in the Royal Commonwealth Sculpture Exhibition. He did not win but he received a personal letter from a Mr. Churchill, then Chairman of the Royal Society of British Sculptors, praising the strengths of the work. Moore still believes that with better directed photography, he would have won. Instead the prize went to a Canadian abstract sculptor. He speaks of Mr. Churchill’s letter with feeling.

Bat and Ball Fantasy simply tells everything there is to tell about cricket in the Corentyne when Moore was a child. Growing up in Manchester, famous for its ground and cricketers, he was nurtured in the thick of those deep and all-encompassing inter-village contests. Whim versus Manchester was no mere cricket match. In ways that C.L.R. James would have keenly appreciated, it was a conflict of civilisations fought out in a remote corner of the British Empire.

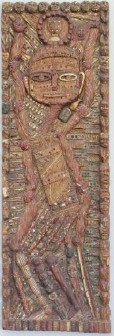

The carving is framed along its four sides. Along the top, ten heads to represent the ten golden hours of sunshine. Along the bottom, the roller used to prepare the pitch. Along the two sides, the spectators clapping their hands, now for the fielding side, now for the batsmen and then, at the end, all cheering for the game. The central figure is a man batting, bowling, fielding, umpiring and cheering. Two arms are upraised. The right hand grips the ball, the left waves the flag. Two other arms end in the bat and the umpire’s two sticks, one flecked with the blood that can flow and frequently did from the fights which would follow a crucial decision. (Figures with many arms are by no means unusual in Moore’s paintings and sculptures. It would be surprising if this carver of Murtis for Corentyne temples did not draw from the rich store of Hindu religious imagery. Did he not, at the time of independence, paint a picture of Hanuman holding Guyana in his arms?) The anatomy of the figure is made up of bat, stumps, pitch, pads. The holes and vertical marks stand respectively for the bowlers and fielders straining to get the batsman out and the batsmen fighting to score their runs. The sinews of the arms are twisted to impact a wicked wrist spin. In the space around the neck of the figure, cups and a pot stand for the refreshments, a not so minor aspect of things. The overall design is wonderfully harmonious and provides a point of tension with the turbulence it depicts. The intricacy and minuteness of detail would become a Moore hallmark. Later on, critics at Princeton would call it filigree.

To complete the depiction of the phenomenon that was the Whim vs. Manchester match, a small coffin and a fowl cock with a smear of blood. What have these to do with a game of cricket? They make reference to the obeah dimension and tell a village tale. A certain Johnson Cort, doing work for Manchester, would walk into the Whim ground carrying his coffin to capture the spirits of the Whim players and “tie them down”. Johnson Cort was the agent of Uncle Hackett, known and feared as Jumbie Coney, the obeah man for Manchester. The “work” for the opposite side was performed by Kali Ram, the obeah man in charge of the Kali church in Letterkenny, a nearby village and one of the many between Letterkenny and Auchlyne with its Kali temple. Moore remembers going to the canefields early in the morning and seeing the circle of blood on the four-path where the Kali worshippers had made a sacrifice. Certain precautions had to be taken. The night before the game, the players would leave their homes and sleep at the safe-house of the manager, Georgie Gray. They were to be called only by their false names, so that when the spirits came calling their names at night, they would not call their right names. For the avoidance of doubt, on the day of the match, pork would be burned in a Capstan cigarette tin on the wind side of the ground to keep away the coolie jumbie which had no liking for the smell of burning pork fat.

All these things claim their place in the small 3’x18” carving. It is a miracle of distillation and symbolic expression. Bat and Ball Fantasy belongs to a group of works Moore executed soon after his marriage to Eula Grant, daughter of a Jordanite elder, in 1955. defying the predictions of his friends who warned that marriage would make his art suffer, he remembers being “overpowered by the inspiration and well-being” that released a flood of intuitive ideas and sent him back to his boyhood memories of everyday life in a Corentyne village. “We can re-educate the minds of people through art. The same as how the Hindus have the murtis, Ganesh and Krishna and Hanuman-ji on calendars and postcards, the African man too has to get his spiritual heroes and surround himself with them so they become a part of his everyday life.”

A reluctant visitor to the city, Moore remains to his fingertips a man of the village. His idiom in painting and sculpture is derived from the village and is for the understanding of village people. His art is in the first place for their consolation and re-education. Few things pain him more than the abandonment of the villages and the desertion of the farms by the young people, many of whom were drafted into the many military and para-military organisations that sprang up and proliferated in the seventies. These days, the situation is made even more grim by the mass emigration that is draining away the life-blood of Guyana. “Without the country people getting proper redemption, Guyana is doomed, doomed,” he says. “There is a too much of a big gap between the so-called educated academic people in the city and the people in the country.” He deplores the neglect into which the villages have fallen – the unpassable dams, the silted middle-walk and side-line trenches, the broken down kokers and bridges, all leading to the collapse of village agriculture in too many places which were once industrious and productive. He deplores the cultural decay into which the villages have fallen, their loss of community with all the generosity of truly communal living. He does not think highly of “all those so-called educated black people living in Republic Park, in Georgetown and the United States,” reserving his admiration for the few doctors and lawyers who have gone back to live in the villages among their people. “The village, the village is the thing.”

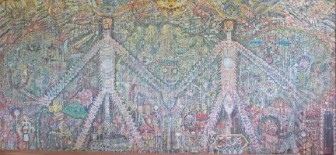

It is hard to think of a depiction of village life, in any medium, more abundant and dense with specification that Jumbie Wedding, one of the epic master works hanging in Castellani House. Begun during his stint in the United States, Jumbie Wedding was completed after his return to Guyana in the mid-seventies. The work is epic not only in size and vision, but also in the dominance of pure narration. In common with the late Gilberto de la Nuez of Cuba, another Caribbean master Intuitive, Moore is a compulsive story-teller in the direct line of the transmitters of old, sitting around a fire and passing on the lore of the people to another generation in the form of stories. And Jumbie Wedding is thick with symbolically illustrated stories imbibed as a child and being passed on. Moore had earlier committed some of them to writing:

“Jumbie Wedding is just to portray and to remember a prophet that we had in the village, Gulluh Alexander. My grandmother used to talk about that man. How he used to walk through the village talking about things that would come to pass, in a prophetic way. And he was a man who when he planted potatoes and he was ready to reap he would walk through the village telling people, ‘Pitete ah banjo. Come ah Liverpool fuh pitete.’ Imagine that! A man with a whole field of potatoes calling out the village to come and reap. So in this one night I imagined myself living in his day.

One night the people say Gulluh Alexander looking up to the full moon. He stood there for a long time. People wanted to know if a next world war was coming, wondering what this man could be seeing because they had a fear and a reverence for him. He told them nothing. Seven days after, he walked through the village and announced: ‘All who gat fowl an duck an turkey ah sit ah dey nest, go look, see wa happen.’ Well, all the eggs had become gander eggs, blue and spoiled. Gulluh Alexander told them: ‘Nah tro way yuh ganda egg but tek yuh ganda egg an mix it wit dag booboo an put it pun yuh farhead because when de moon eclipse, yuh gon get a jumbie wedding. De rain gon fall an de sun gon shine underneat de tamarind tree. An de spirits from de fire, de hail, de earth an de water would all come meet up together’. The two main persons who came down to the wedding were the Moongazer and his wife.”

Their towering figures dominate and order the painting. All else proliferates around them: all the jumbie stories and the countless episodes from the life of the village. “Coming from the moon, they are always cool, so the fire spirits had to pass through the bodies of the Moongazer and his wife to cool down before they could go under the tamarind tree for the wedding. All the people that did wrong to the community, their spirits have to come back to that Jumbie Wedding and ask for forgiveness, and make a pledge that they would do right.”

Here old village disputes are revisited in a communalistic atmosphere, a commune of jumbies. Notorious criminals come back, including rapacious landlords. Even Tengar the blasphemer, whose spirits lived in the forest. The wedding is between a Corentyne jumbie boy and a Buxtonian jumbie girl. “Tengar was a Buxtonian who used to say, ‘If the Lord and God had wanted you to be safe, He would have provided a raft for you.’ Tengar had to come and make confession and because of the wedding, the wars in the bush between Corentyne men and Buxton men who came to blows over the gold fields, ended. The Berbice policemen were all coming to marry the Buxton girls.

The jumbie wedding underneath the tamarind tree is the primordial zone of forgiveness and reconciliation.

Moore cannot understand why no one remembered Survival City at the time of the Omai disaster, since it was a prophetic sculpture. Survival City is the purest expression of Moore’s vision of the ideal human community. Carved in 1986 it is buildings and details of economic activity, based on a system of bartering, it is Moore’s vision of the utopia, the fabled city in the forest ruled by righteousness and respect for the gift of the earth and ready to protect and defend itself from a ravenous world system. Survival City has been built by people who have turned away from the so-called civilised society to go into the forest to carve out and start a new city. They have turned their backs on the inhumanity of a system where the few amass mountains of wealth and the many lack the means to earn a living. “But in a communalistic society, everybody should produce and the wood-carver can exchange his pieces of work for yams and tomatoes and whatever else he needs. That is my personal vision of a new economic order. We must bring back people to some of these communalistic ideas. The main face of the City has bullets for teeth and a moustache, signalling readiness to band together and defend the city against any aggression. The overhanging chandelier of calabashes and bells protects the city from pollution and other deadly dangers.

It may come as a surprise to some to learn that Moore has always been on the side of national reconciliation. Among his many disappointments with the 1763 Monument, is the absence of the wheel of eternal revolution which was designed to be a part of the monument. The wheel is made of the cup, the coconut tree and the sun, the symbols of the main political parties at the independence period. The wood carving Integration Mask, with the coconut tree growing out of the cup with the sun overhead, speaks to the same issue making use of the same symbols.

He prefers the original maquette to the monument which he never got the chance to complete. There was the chasing to be done on Cuffy’s face, for instance. I remember once seeing a photograph in the newspapers of two boys at work cleaning the face and body of Cuffy. I have no wish to add what I wrote then: “From all the comments I have heard from all quarters over the years, I must be in a tiny minority that believes deeply that Philip Moore’s monument, with Gonzalez’ Bob Marley in Jamaica (not in the street but withdrawn into the Museum after public outrage), are among the most powerful and eloquent public monuments anywhere in the region. The 1763 Monument is awesome in a way that Broodhagen’s awkward “Bussa” in Barbados and even the serene José Martí presiding over the Plaze de la Revolución in Havana are not. It is true that the popular rejection of “Cuffy”, as he has come to be known and hated, has also to do with the fate of non-representational pubic art in the region as a whole. No Henry Moores and Barbara Hepworths for us. We like our monuments realistic, as recognisable as our next door neighbours. Matters are not helped by the security-conscious plinth designed by a local architect. To be bomb-proof, the story goes. Philip Moore did not intend Cuffy to be in the sky: such a thing would have been a negation of all that the insurrectionary slaves stood for and a violence to the artist’s own deeply held convictions and notions of godmanliness. Moore intended him to be at earth level, monumental through the force of inner strength, not of mere scale. The complex symbolic text inscribed all over the body of the slave, the allegorical objects, the exquisite bas-relief panels – all this will be revealed to every child who can play where Cuffy stands. Perhaps now that justice has been seen to be done to Queen Victoria, the authorities will turn their attention to the humanisation of the 1763 monument. A recent newspaper photograph of a young man perched atop Cuffy brought me great pleasure. Not because he was scrubbing him up for the Queen, but because he restored Cuffy’s humanity. Bring him to earth so that we can share in his power.”

A lasting disappointment is that the work he has devoted a lifetime to producing is not serving the purpose it was created to serve. He feels deeply that instead of being rolled up and stored away to gather dust and deteriorate, the work should be carried in exhibitions across the country. To the schools, the community centres, to village festivals and other ceremonies. (The large canvasses are not stretched and framed but designed to be threaded with cord and hung.) As a young artist on the Corentyne, Moore carried his works from place to place, sometimes by donkey cart, exhibiting them in schools and other public places. He is not a museum artist in the sense that Burrowes and Moshett and Greaves are museum artists. His dream is of a meditation centre where the works will be placed in room after room creating a total environment for the explorations of the spirit. And what a radiant place that would be. A people professing respect for the river of works which has flowed from the mind of Moore for the last half a century would go to great lengths to ensure that Moore’s Methodical Meditation Museum come into being while he is still among us.

Now in his seventy-fifth year, he is hard at work completing the three pieces for the Santo Domingo exhibition: Old Gods Do Not Die Young, The Cultural Centre, Bridge of the Diaspora. His powers have not diminished. He carves only on commission these days. He continues to sell off the occasional piece to make ends meet. He is saddened that art does not receive its due, that the young artists are living from hand to mouth, reduced to turning out baubles for the tourist trade. “If we can raise money for the flood victims, why can’t we raise money for the artists?” he wonders.

I left him working on the Bridge of the Diaspora, dominated by the figure of Mother Africa, its architecture composed of white bodies and boats full of their black human cargo. I have been thinking of his great bridges, the Brooklyn Bridge of Stars and Stripes (“Stars for the whites and stripes for the blacks”), with its underground and ghetto hell in the shadow of the sparkling towers of Manhattan; of the delicate Kissing Bridge over the pond of lilies in the Botanic Gardens, remembering the music at the band-stand and the promise of romance afterwards. In his mind were the bridges of his childhood, the coconut tree bridge over a trench, the bridge on the dam for the tractor to pass, and, being who and what he is, the bridges we need to build inside of ourselves if we are to integrate mind, soul and body.

Could anyone in 1979, year of rebellion and sharp steel, have imagined that in 1996 I would be sitting in President Burnham’s attic thinking about art and its power to redeem? Philip Moore is the bridge I crossed to get here.