Amerindian art in Guyana has generated forms in painting and sculpture which are the most unique in the anglophone Caribbean. They also hold a very interesting place because they may be described as both the most ancient and the newest forms in the region as a whole. These forms are among the most distinctive and fascinating, but the critical accounts are yet to catch up with them.

Closely related to that is the state of Guyanese archaeology. Amerindian art is the most ancient in the Caribbean because it has its roots in the oldest civilisations in the region. These pre-Columbian civilisations existed in the Guianas, within the wider region of Amazonia in which there have been advanced archaeological finds. The research and publications about this pre-history which is older than the Christian era, hold significant implications for both South America and the West Indies. But the achievements in Guyanese archaeology and anthropology are insufficiently celebrated in the region.

Interestingly, the work of Guyanese Stanley Greaves was selected to grace the cover of Caribbean Art by Veerle Poupeye, the most authoritative text on Caribbean art. Similarly, Denis Williams of Guyana was recognised and decorated by the UWI as a leader in Caribbean archaeology. However, despite these significant notices, the place of Guyana in the region’s art and archaeology has not been truly established.

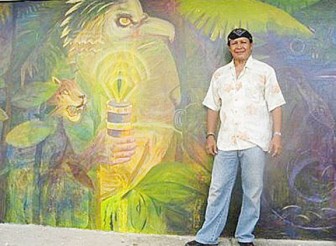

These all came together in a meaningful way on Saturday, May 5, when Guyanese painter and archaeologist George Simon was awarded the 2012 Anthony N Sabga Caribbean Award for Excellence for his work in The Arts and Letters. This certainly pointed a good deal of attention to Guyanese art and archaeology as it was widely covered by the media in Trinidad and beamed to other countries in the region. It was of particular interest to the Commonwealth of Dominica since the winner of the equivalent Award for Science and Technology was Professor Leonard O’Garro from that island. The third award was for Public and Civic Contributions, and that one remained at home since it was won by Trinidadian Paula Lucie-Smith.

These all came together in a meaningful way on Saturday, May 5, when Guyanese painter and archaeologist George Simon was awarded the 2012 Anthony N Sabga Caribbean Award for Excellence for his work in The Arts and Letters. This certainly pointed a good deal of attention to Guyanese art and archaeology as it was widely covered by the media in Trinidad and beamed to other countries in the region. It was of particular interest to the Commonwealth of Dominica since the winner of the equivalent Award for Science and Technology was Professor Leonard O’Garro from that island. The third award was for Public and Civic Contributions, and that one remained at home since it was won by Trinidadian Paula Lucie-Smith.

These presentations followed closely on the heels of the second CMS Bocas Literary Festival which celebrated and exhibited Caribbean writing in Port of Spain one week before the Sabga Awards. But even more than the way in which this literary feast highlighted regional writing, the award to George Simon drew some attention to the place of the artist and his country in a Caribbean context, and turned a spotlight on work that had been too much in the dark before now. The occasion was given great prominence and was very much the event of the week, hosted as a red carpet affair in Trinidad’s new NAPA complex for the performing arts, exclusive to Trinidad high society but beamed live via television to the rest of the country and the region.

What is of major interest, however, is the way it brought Simon’s work and Guyanese art and history, into perspective. A significant irony is that the honouring of this artist, who is a Lokono and a member of Guyana’s nation of ‘First People,‘ coincided with the commemoration of Arrival Day in Guyana (May 5). Within a complex matrix of indigenous and immigrant cultures in the country, discoveries about the old civilisation and the new art were recognised. It was a threshold on which the meeting of the pre-Columbian and post-Columbian Caribbean was rehearsed. It reflected a tension between the ancient, misunderstood roots of Amerindian cultures and all those others that arrived in the wake of Columbus’s caravels. This meeting point helped to focus the new discoveries made through archaeology about what happened before, and the art which brings them all together.

What was also observed in the awards ceremony and all the attendant literature is that much more was articulated about the archaeology than about the art. This was definitely the case with the excellent documentary about Simon and his work that was screened at the ceremony. It seemed easy enough to follow the story of civilisation, but the nature and characteristics of the art are not nearly as easy to describe. Simon’s painting, its methods and depth of meaning, and what it represents in Guyanese art are new to the Caribbean, and certainly to national and regional comprehension.

Simon is an Associate Fellow at the University of Guyana, where he has been a Researcher in the Amerindian Research Unit and a lecturer in the Division of Creative Arts. He was born in an Arawak (Lokono) village and was later educated in England with the help of an English priest, earning a degree in Art at Portsmouth and a Masters in Archaeology at London. He taught at the Burrowes School of Art and worked with Denis Williams and with the Walter Roth Museum. In collaboration with fellow UG artist Philbert Gajadhar he completed two archaeological exhibition sites in the National Museum in Georgetown, a map room and a life-size replica of the giant sloth in its habitat. The sloth itself, one of Guyana’s pre-historic creatures, was a major recent archaeological find.

His current archaeological work is his most important to date. It is a joint project with three institutions: the Universities of Wisconsin and Florida and the University of Guyana, following an agreement signed in 2011. Simon proceeded as part of a team involving the late Neil Whitehead in addition to Michael Hackenburger to investigate a field of man-made mounds in a large area up the Berbice River. Although not yet analysed, the samples found so far provide evidence of the existence of advanced, complex, populous settlements dating back some 5,000 years. The discoveries are expected to unearth important new material about pre-Columbian civilisation.

It is from similar ancient cultures that Simon takes information for his art. Decades ago one of Guyana’s most acclaimed artists, Aubrey Williams, was inspired by the Amerindian petroglyphs and motifs around which he built several paintings and the Timehri murals at the airport. Other artists Stephanie Correia and Winslow Craig applied factors of Amerindian art and culture in different ways, but what Simon created set off a new wave of art, primarily among Arawak artists. These involved a group of sculptors led by Oswald Hussain and including Lynus Klenkian and Telford Taylor, who were among many taught by Simon in St Cuthbert’s Village. Their work arises from the mystical depths of Lokono spiritual beliefs, myths, the natural environment and the animals of the rainforest.

At first Simon produced a series of large paintings on themes around hunting and Amerindian interior life, but after his years spent in England, Chad, Sudan, Canada and Haiti, his work deepened and became more complex. This complexity arose from his use of Amerindian traditions and spiritualism, but some of it was a multicultural influence including African, Haitian and East Indian traditions. A very good example of these mergers is the triptych on a mural in the National Cultural Centre (2008), as well as another strongly environmental mural done with students in the Umana Yana, and the Palace of the Peacock: Homage to Wilson Harris (2009) mural on the UG Turkeyen Campus done with collaborators Gajadhar and Anil Roberts.

The triptych and the Harris mural are far more impressive works, but the triptych is the deepest in this context. It is a tribute to womanhood and depicts female water spirits with the influence from different cultures including Haitian traditions, Guyanese African and Indian spirits as well as the Amerindian. But while this produces extremely interesting art, Simon still manages to take it to another level with later paintings produced in 2010 and after. There is a suite of smaller paintings called The Shaman’s Journey Along the Milky Way in which the artist ‘fictionalises’ his own experiences and stories he was told or knows from Amerindian traditions. He was certainly matured spiritually in the process of his sojourns through Chad and Haiti, and he calls that period of his life his Shaman’s journey. The result was the series of paintings which are abstract, but which are enriched by images, motifs and the use of colour and brush techniques to reflect the appearance of the constellations, the Milky Way, superimposed upon the traditional spiritual images and motifs from the stories of the shamans.

So that Simon brings to Guyanese abstract art, a form of work informed by Amerindian mythology and spiritualism. Another step further within this form is his use of work which is not abstract, but more surrealist and expressionistic. These are even deeper experiments with spiritual beliefs. They are close to the type found in the work of the group of Lokono sculptors among whom Hussain is the most outstanding. This is art of the environment reflecting animism, the landscape and the rainforest. Most striking here is Simon’s work on Kanaima. There is a particular painting which begins as if it is a realistic life portrait; it is a picture of a girl done from a posed semi-nude model. But the artist superimposes the many animistic images and motifs from the rainforest. He makes much use of the jaguar and the serpent (with which he introduces some Haitian spiritualism as well; and even in other instances the Mexican Aztec Indian bird-serpent Quetzalcoatl) to reflect Kanaima.

The girl then assumes protean forms because the Kanaima is a known shape-shifter. He is a man but is highly trained to change his form – often to a jaguar, but can immerse himself in the forest. He is a hunter of men and animals and can therefore be deceptive in both sound and appearance. Simon infuses these beliefs into paintings which, like that with the girl, depicts a jaguar whose spots become leaves in the forest, the eyes of the peacock, feathers of birds, colourful patterns on snakeskin, among other things.

This form of painting tells tales of the Lokono’s experiences with the rainforest. It does with paint what Hussain and Klenkian do with wood. Hussain’s grotesque and awe-inspiring images of spirits which inhabit the forest and its birds is strikingly representative of this new art that is the most unique in the Caribbean. Simon takes the same animism, inter-related to mythology, and creates a style that thoroughly represents the characteristics of this new emerging art. He further fuses it with other folklore and cultures to carve out his own unique brand within the dynamic Amerindian painting.

It is hardly expected that the Caribbean audience will be immediately familiar with all the belief and traditional consciousness that have gone into the works, but what they get is a rich new form; the newest development in Caribbean art. It is not surprising that it is not readily understood and articulated, and was thus under-represented at the Anthony Sabga awards.