LONDON/PARIS (Reuters) – Iran is poised to offer the Syrian authorities a short-term food lifeline with vital grains purchases as Western sanctions and mounting violence deter trade houses from doing deals with Damascus, international traders say.

Both are targets of Western sanctions that, while not intended to disrupt food imports, have hurt shipments of all kinds by complicating financial transactions. Richer and more practised in the ways of sidestepping such embargoes, Iran seems set to help its struggling ally, though its own means are limited.

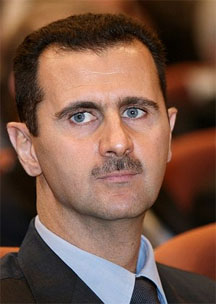

“Iran will try to help Syria,” said a senior trader at a major international grain house in France who likened Tehran’s interest in helping Syrian President Bashar al-Assad stave off food shortages to Algerian state aid last year for Tunisian and Libyan autocrats who were trying to stifle popular unrest.

“I think most of it will be done via the black market,” the trader added, meaning that bread wheat, animal feed and other grains could be shipped to Syria by Iran discreetly, avoiding the normal practice of international public tenders.

Numerous sources in European grain trading centres and the Middle East concurred that Iran, a major energy exporter which has been under Western sanctions for years due to a dispute over its nuclear programme, would help Assad, a key Arab ally whose government has been hit with Western and Arab League bans on banking and other dealings due to its crackdown on protests.

“It’s a given that Iran will help Syria,” said another grains dealer in western Europe, speaking on condition of anonymity, as is common in the business. “But it won’t be on the radar. It will be a bilateral agreement between them.”

Grains traders said Iran, which buys its supplies through public tenders and in private deals, would also aim to help Damascus by turning a blind eye to its own private merchants re-selling wheat to Syria.

Government agencies usually buy through public tenders where the quantity required, shipment schedule and other details are sent to international trade houses with a deadline for bids. Purchases by the private sector are generally less visible.

Separated by a land border, some of the ways Iran could get supplies to Syria would be on trucks via Iraq or Turkey, which have borders with Syria. Separately, shipments could be re-routed through Iraqi or Turkish ports and then onto Syria, European and Middle East grain traders say.

Unable to finance the big international grain purchases it has been used to, Syria has engaged in a desperate search for grain that has forced Damascus into an array of unusually small deals, many arranged by middlemen around the Middle East and Asia.

But the amounts agreed have been nowhere near meeting Syria’s reliance on imports for about half of its annual needs of 7-8 million tonnes of grain, a situation that threatens to sap domestic support for Assad as he faces mounting international condemnation and domestic defiance of his rule.

Tehran, under pressure itself for refusing demands from world powers to stop enriching uranium they see as part of a secret nuclear weapons programme, has experience that can help an ally in the regional confrontation which pits Shi’ite Muslim, non-Arab Iran against the Sunni-dominated Arab states.

“Iran’s relative success in circumventing sanctions, which have complicated efforts to import grains and other basic food staples, derives from its ability to find alternative ways to pay for imports,” said Torbjorn Soltvedt, senior analyst at risk analysis firm Maplecroft in London.

Iran, unlike Syria, is increasingly working around the restrictions using covert payment systems including non-dollar currencies and its oil and gold in exchange for goods.

However, even Iran, needing to feed its 78 million people, has limited resources to help Assad, whose Alawite minority, religiously tied to Shi’ite Islam, has dominated Syria for four decades, even though most of its 23 million people are Sunnis.

“Although Tehran is likely to continue to provide financial and logistical support to Damascus, domestic food security concerns may limit the degree to which it will be able to meet a significant shortfall in the supply of grain and basic food staples in Syria,” said Maplecroft’s Soltvedt.

A trader based in the Middle East said Syria was most likely to benefit from profit-driven private traders in Iran rather than from direct aid from the Tehran government: “Iran has to continue to sort out its own food problems, so any assistance to Syria is not viable by the government,” the trader said.

“It could become a private trade brokered by Iranian middle men,” he added.

Traders involved in the supply of grains to the region say the coming harvests in Syria and Iran may also help the Syrians for a short period, though its food requirements remained critical.

“Syria’s crop is coming in and this will take some of the immediate pressure off the government,” said one trader in Hamburg, a key grain trading centre in Europe.

“The United Nations aid agencies are also doing big buying of Syrian aid cargoes, so the Syrian government may be happy to let the international aid agencies foot a large part of their food bill.”

Turkish intervention

Turkey was also likely to remain as an intermediary for both Iran and Syria, traders said. In recent days there have been grain deliveries to Syria via the Turkish port of Mersin, while Turkish banks have been used for Iranian and Syrian deals.

Turkey, exasperated by its one-time ally Assad, announced late last year its own sanctions targeting the Syrian government. But it specifically said it would avoid measures that would add to the hardships of the Syrian people.

“Turkey will remain the key factor for the Iranians and they still look like they are keeping lines open,” one trader in western Europe said. “So bringing in supplies from Turkey is a viable option for Iran.”

Syria has few options but to look for unconventional supply routes: