By Kevin De Silva and Mark Chatarpal

Kevin De Silva is a fourth year student at the University of Toronto.

He is completing his undergraduate degree in Political Science and Caribbean Studies, winning the United Network of Indo-Caribbean Toronto Youths (U.N.I.T.Y.) Scholarship in 2010. He is co-president of the Caribbean Studies Students’ Union, and has been chief editor of Caribbean Quilt for the past two years.

He is completing his undergraduate degree in Political Science and Caribbean Studies, winning the United Network of Indo-Caribbean Toronto Youths (U.N.I.T.Y.) Scholarship in 2010. He is co-president of the Caribbean Studies Students’ Union, and has been chief editor of Caribbean Quilt for the past two years.

Mark Chatarpal is currently studying at the University of Toronto. He is co-president of the Caribbean Studies Students’ Union, and co-editor of the Caribbean Quilt. With a love for his country Guyana, Mark has maintained strong connections with his home, family and friends. In addition to his studies, Mark does small-scale community based development in Guyana and Roraima, Brazil. In 2002 he won an award for poetry from the International Society of Poets.

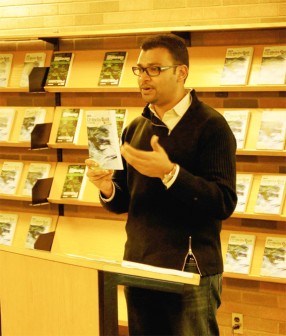

To the clapping, cheers, laughing, and even crying of a packed audience at University of Toronto’s Ivey Library, the Caribbean Studies Students’ Union [CARSSU] launched its 2nd edition of the Caribbean Quilt on March 30th 2012. Caribbean scholars such as Dr. Arnold H. Itwaru, founding Director of the Program, were commended for the financial and emotional support provided to the Caribbean Studies Students’ Union in publishing the journal. Current Director Dr. Alissa Trotz was also recognized for continuing the work of developing the Caribbean Studies Program in a space often hostile to frank, no-nonsense engagement. Young and rising diasporic Caribbean scholars were given a chance to share their published pieces with a receptive crowd in a budding community.

All of these things are in many ways historic: that such a space is slowly being strengthened, but more than this taken seriously, is very, very new, even in Toronto. We are writing this article to stress this, but more than that to give thanks to inspirations on the “front-lines” of Caribbean society. One of these inspirations is Duane Edwards, president of the University of Guyana Students for Social Change. His essay, and his insights related to the works of Wilson Harris is the first piece in the Quilt. This is not by accident. What Edwards stresses is conceiving of Caribbean societies as wrestling with a history of colonialism and the plantation economy; the way in which the institutions and personality types that historically regulated and profited from slavery and indentureship still dominate in the present. Opening our journal with authors who directly confront these realities in the Caribbean is indicative of our commitment to building inclusive, transnational pedagogies.

Silence in modern day Guyana is constantly disturbed by the buzzing of chainsaws and the roar of diesel generators powering mining operations in the interior. In the capital, the clamour of misguided traffic and the stench of poor drainage contribute to the desensitization of the Guyanese mind. The state of the University of Guyana is deplorable; the dilapidated infrastructure is in need of immediate remodeling. Promises of financing during the presidential debate appear so far to have vaporized in the immediate post-election landscape. All this amplifies the growing sense of alienation amongst Guyanese people, not only from nature as in Harris’s theory, but also from hopefulness. Our goal for the Quilt is to showcase works by individuals who are not generally given the spaces to express dissenting opinions, and to cultivate a culture that encourages these views.

At the heart of what Edwards through Harris asks us to consider, is what the development of a Caribbean Civilization might look like. This is no simple question, and it is not one that the diaspora has forgotten. For us as students, taking that question as a starting point can open limitless possibilities for building: How can quintessentially Caribbean thinkers and philosophies be deployed to mobilize and empower citizens, both in the diaspora and the Caribbean? How can development occur in such a way as to limit the break-up of communities, but still promote individual creativity? What would the built space of such a society look like, if it is not to be imitating another; how would it interact with the “natural” in places like Guyana?

These questions cannot be dead because they have not yet been answered; they are truly exciting, but they have been brushed aside. Nor should they be labelled fantasies. Working through the material for the Quilt was a lengthy process though a rewarding one. Professor Melanie Newton of the History Department at the University of Toronto played an instrumental role in giving us access to high caliber student material. It was also inspiring to see the depth and breadth of student thinking on questions related to Caribbean history and its relevance today.

What the creation of the Quilt has taught us is that there are many young people out here in the diaspora with unique and innovative skills who feel suffocated in the Great White North. Self-critical young people do take these questions seriously, are curious about their roots, and do still very much see their academic work, even their psychic states, wrapped up in a Caribbean that they want to learn more about.

Our journal touches upon many themes in the Caribbean at large, and we hoped for its subject matter to have a resonance in the Caribbean and in the urban West, a difficult thing to balance. Aside from essays and poetry, the journal has in the past showcased paintings, installations, and other types of media. It features the poems of students who do not wish to be the “affirmative action friends” of their peers, for example. Tammy Williams, a student of Jamaican descent at the University of Toronto, read her poem to a silent, sympathetic audience, many of whom have experienced being seen as “exotic,” with “funny” accents to non-Caribbean peoples all too-often. The first 3 stanzas read as follows:

“So… /You want to take my picture? put it on your website? /class yourself among they that honour diversity?

You want to exoticize my tongue, /tug at my hair, /then boast images of my black skin /in your track bottoms and throw back tees /as if I am any more than a minority?

I’ll pass /cuz I’d much rather not /sit in to fill in the blended shades /of your acceptance packages…”

Other pieces wrestle with the significance and meaning of political independence while severely uneven economic dependency persists. Still others address the internal power imbalances of Caribbean societies plagued by a small elite lording it over populations suffering extreme poverty (particularly in the case of Haiti). Monica Silberberg’s piece addresses the significant historical strides made by leaders such as Michael Manley in the nationalization of the Jamaican bauxite industry.

Stitching together a series of experiences, at once Caribbean-based and diasporic, may be a critical step towards re-shaping beliefs on both sides. A self-critical, cross-national quilt which addresses the ills of both worlds can go a long way to making them more inhabitable. We hope that our little journal, and the essays found within it, has moved a step forward in doing this.

*The Caribbean Quilt: Volume II, 2012 Edition has been featured at the University of Toronto and “A Different Booklist” in Toronto. It will also be featured at the University of the West Indies and the University of Guyana. For more information, please e-mail: students.carssu@gmail.com.