All politicians lie, or sometimes play games with the truth, but the Presidents of Bolivia and Ecuador were so off the mark when they asked the Organization of American States to effectively kill its Human Rights Commission that one can only wonder whether they were being ignorant or blatant liars.

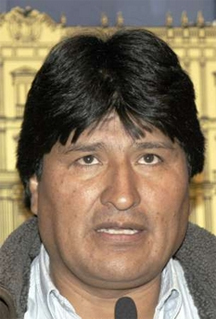

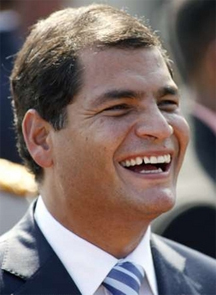

In their speeches to the 34-country OAS annual meeting held earlier this week in Cochabamba, Bolivian President Evo Morales and Ecuadoran President Rafael Correa argued that the OAS’s independent Human Rights Commission — which has criticized their countries for human rights and freedom of the press abuses — should be significantly reformed because it allegedly criticizes leftist countries while ignoring US abuses.

In his opening speech calling for the “reorganization of the jurisdiction” of the OAS’s Inter-American Human Rights Commission, in which he asked that the group be stripped of its independence and report to OAS member governments, Morales demanded that the commission turn its eyes on US human rights violations.

In his opening speech calling for the “reorganization of the jurisdiction” of the OAS’s Inter-American Human Rights Commission, in which he asked that the group be stripped of its independence and report to OAS member governments, Morales demanded that the commission turn its eyes on US human rights violations.

“If it doesn’t want to address human rights abuses in the United States, it’s better that the Inter-American Human Rights Commission disappear altogether,” Morales said.

Correa, who has led a campaign against the commission since it criticized him for harassing the daily El Universo and other independent media, said that “we cannot accept double standards,” and accused the OAS and its human rights group of “neo-colonialism.”

In fact, if the Presidents of Bolivia, Ecuador and Venezuela’s Foreign Minister Nicolas Maduro, who teamed up with them, had spent one second doing a Google search of the OAS Human Rights Commission’s work, they would have found that it has criticized the United States more often than most other OAS member countries.

Consider:

Last year, the commission passed 11 resolutions requesting the United States to take urgent actions to correct human rights abuses. The only country that received more commission requests for urgent corrective actions was Honduras, which was the target of 12 commission resolutions.

Colombia ranked third among the countries with the most commission urgent action requests, Mexico fourth, and Argentina and Cuba were tied for fifth place, with three requests each. By comparison, the commission passed only one urgent action request against Venezuela, one against Bolivia and one against Ecuador last year.

In 2002, after the US government opened its prison camp for suspected international terrorists at the US military base in Guantanamo, Cuba, the commission was among the first in the world to demand that the United States “take urgent measures necessary to have the legal status of the detainees at Guantanamo Bay determined by a competent tribunal.”

In subsequent years, the commission held at least six hearings about its request to the US government, and issued separate resolutions demanding US action to protect the rights of two Guantanamo detainees. In 2006, the commission passed a resolution urging the United States to “immediately close down the Guantanamo prison camp.”

The commission recently issued a 175-page report blasting the United States for the indiscriminate arrests of undocumented immigrants. In 2011, the commission also requested urgent action from the US government not to extradite at least 38 detained Haitian immigrants who suffered from serious health problems.

My opinion: The United States and Canada, which defended the commission’s independence at the OAS meeting that ended Tuesday with a decision to postpone a final ruling until early next year, are not free of blame in this debate.

Many of their critics rightly accuse the United States and Canada for failing to ratify the Inter-American Human Rights Convention, which has been signed by most OAS members and gives mandatory powers to the Human Rights Court, the top OAS-associated human rights body.

But the Venezuela-Bolivia-Ecuador offensive against the commission, and their leaders’ tirades against independent human rights groups, such as Human Rights Watch or Amnesty International, are part of a shameless offensive to demonise any critics of their governments’ abuses as “US puppets.”

The OAS Commission, perhaps the only OAS agency that does good work, deserves credit — much like Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International — for criticizing governments who violate fundamental freedoms across the political spectrum. Morales, Correa and Maduro may be used to saying what they want when they are talking at home, where they control most of the media, but they look pretty unscrupulous elsewhere when they make these kinds of accusations, which anybody with access to the Internet can prove wrong in a matter of seconds.

© The Miami Herald 2012. Distributed by Knight Ridder/Tribune Media Services.