When are two bodies and a hand equal to 45?

For Anglican priest, John Peter Bennett the answer was simple. His explanation helped noted archeologist Denis Williams in his interpretation of Amerindian petroglyphs which culminated in Williams’ seminal work ‘Petroglyphs in the pre-history of Northern Amazonia and the Antilles’ published by Advances in World Archeology in 1985.

In his letter, now in the hands of the Walter Roth Museum of Anthropology, Bennett -in what was termed his “motive system” by director of the museum, Jennifer Wishart – explained that in Amerindian culture, a drawing of one hand meant 5; two hands and a foot meant 15; a body meant 20; a body, two hands and a foot meant 35; and so on. This was reflected in petroglyphs which were studied extensively by Williams and Bennett’s explanation helped Williams in his interpretation of them, Wishart said.

But Bennett was more than an interpreter of symbols. In a time when the native language was disappearing, he recorded and preserved Loko – the language of the Arawaks or Lokono. Not widely known, he is now being hailed for his work in linguistics and the preservation and propagation of Amerindian languages specifically, Loko. “For me he represented what is a linguist’s dream,” said Professor Ian Robertson of the University of the West Indies. Robertson spoke during the University of Guyana’s Amerindian Research Unit programme, ‘Asserting the Amerindian Presence: The life and work of JP Bennett,’ held on Tuesday. Bennett was, Robertson said, “one of the most significant people I have met in my time in the field of linguistics.”

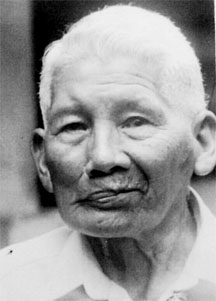

Bennett, who died in November last year, was the first Guyanese Amerindian to be ordained as a priest and a canon in the Anglican church and was outstanding in the field of language and culture. He was worried about the future of the Arawak language and his concerns led to the compilation of an Arawak/English Dictionary, a teaching guide with 28 lessons in Loko/Arawak, the translation of some of the Gospel books into Arawak and the publication of The Arawak Language in Guyanese Culture. His work in the indigenous language brought him much acclaim and in 1989 Canon Bennett was awarded the Golden Arrow of Achievement. A book of his correspondence with Richard Hart edited by Janette Forte, Kabethechino: A Correspondence on Arawak was also published. He also contributed to the work of other scholars and linguists.

Wishart recalled meeting Bennett and learning about his unpublished Lokono-English dictionary and his desire to have it published. Her interest was aroused and her work started then, she said.

Professor Walter Edwards of the Wayne State University noted that Bennett’s work was devoted to promulgating to the world, the richness of Loko and teaching teachers to be aware of the properties of the language. Robertson, meanwhile, said that Bennett was imaginative and had a sense of humour. “He had a conviction about what he did,” he said also recalling the humility of the priest. “He just was a decent human being, at peace with himself and his God and willing to entertain us with his sense of humour.”

For Ramona Bennett, the humble priest was also her grandfather. She recalled the Amerindian tales that he wanted published but to this day, are not. She worked with him on the compilation, Loko Stories. One was a myth about the Milky Way which in the Lokono culture was called the clay diggers trail. In the packed theatre, she read the story aloud.

Her grandfather would have been very happy and proud that his work is continuing to be of importance, she said.