During the earlier period of this country’s history, one or another of the Dutch colonies which once occupied the space that is now Guyana, came under periodic attack from French or English raiders. The end of the 17th and beginning of the 18th centuries were particularly difficult times for the local Dutch, who never knew which flotilla bearing their enemies might be rounding the bend of a river on any given day.

At this period, these invaders did not stay; they were privateers really, in other words licensed pirates who were financed by investors in their home countries to sail out across the ocean and plunder their foes. In the case of France, King Louis XIV himself invested money in some of the corsairs, as they were known there. In circumstances where his treasury was under pressure, it was a cheap way of fighting those countries with whom he was at war, since he didn’t have to bear the whole expense of fitting out the ships and could make a profit by taking a cut of the spoils.

It was not until 1781 onwards, when privateers in this part of the world had long since faded into oblivion, that the French and the British actually occupied Guyana – without a shot being fired, it might be added. For two decades the colonies of Essequibo, Demerara and Berbice were shuffled between the British, French and Dutch like the pieces on a board game, until the British assumed control for the last time in 1803. (1781-82 – British; 1782-84 – French; 1784-96 – Dutch; 1796-1802 – British; 1802-03 – Dutch; 1803-1966 – British. Formal recognition of British control came in 1814.)

Raiders

The present story has its origins in one of those interminable wars which have plagued Europe over the centuries. This one was the Spanish Succession War, which began in 1701 and went on for thirteen years, almost ruining France in the process. Louis XIV issued what were called letters of marque to private individuals to raid in the colonial theatre, and as mentioned above, invested himself in some of these pillaging enterprises.

The one which concerns us here was that led by Jacques Cassard (sometimes spelt Cassart), a merchant captain when the Spanish Succession War broke out, who had experience as well in the French navy. Like many other sea captains, he became a privateer on the outbreak of hostilities, and earned a name for himself both in fighting the British and in terms of his seizure of enemy merchantmen. As a consequence of his exploits, in 1711 he was given command of a squadron of six ships, and he set sail with these with the intention of plundering the Cape Verde islands, which were owned by the Portuguese, and colonies in the British and Dutch Caribbean. The financiers for 50% of the squadron were a group of Marseilles shipowners and merchants – Jean Dieu, Michel Glaise, Nicolas Guitton and Roussel and Co – whose interest in the enterprise extended beyond the merely patriotic. The other 50% was supposedly put up by Cassard himself, although it is always possible that since there was a large contingent of royal troops on board, the King himself might have been a sleeping investor as well under cover of Cassard’s name.

The wealthiest Dutch colony on the South American mainland by far was Suriname, and it was also the furthest south. After entering the Caribbean Cassard made a beeline for it, therefore, and it was only relieved of the corsairs’ unwelcome attentions with the payment of 622,800 guilders – an enormous sum of money in those days. According to the eighteenth century writer, JJ Hartsinck, while Cassard was in Suriname he captured a Swiss, who informed him about the situation in Berbice. He wasted no time in detaching three ships from his squadron, therefore, and dispatching them there under the command of Baron de Mouans. At that time Berbice was owned, not by the Dutch state, but by the Van Pere family who lived in Vlissingen in the Netherlands.

Baron de Mouans

Most of the details of what happened after the French put into the river are derived from the Governor of Berbice, Steven de Waterman, and four of his Councillors who wrote the Van Peres about the sequence of events in a letter dated 2nd January, 1713. After the usual niceties, de Waterman opened his account by saying:

“We have had the misfortune of a visit by Baron de Mouans… On the 8th November, 1712, Baron de Mouans entered the river with three barques and some double sloops, three mortars and 600 royal troops…”

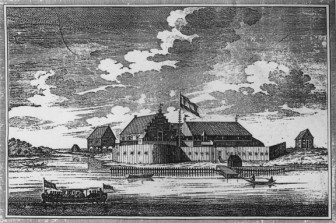

The Dutch headquarters in Berbice was situated about 56 miles upriver, but by the 10th November, the French had drifted with the tide far enough upstream to reach the main plantation in the colony, called, appropriately enough, Head Plantation. This placed them conveniently close to the headquarters of Fort Nassau, which was a little higher up, and from here they reconnoitered the land all around. Following this reconnaissance, they entrench-ed themselves on a bend in the river where they duly planted a mortar which they trained on the fort.

That completed, a French officer representing de Mouans then presented himself at Fort Nassau to ask whether the Dutch garrison would not prefer to surrender; if it declined to do so, he explained equably, then it would be compelled with bombs to submit, and the colony would be laid waste.

It would seem that the Dutch believed they had a reasonable chance of resisting a French onslaught, and so they responded that they “would await [French]… intentions.” Continuing the courtesies of the encounter, the Frenchman then took it upon himself to advise the Dutch that in that case they could expect the bombing to begin in the evening.

True to his word, the bombing began at 7 o’clock that evening, and between then and 4 o’clock the next afternoon, 19 bombs exploded. This was less serious than at first appeared, because several exploded above the building, although pieces of them fell into the fort. The French later added two more mortars from the ships, and at night bombs were fired from three mortars at the same time. Within a period of twenty-four hours, said the Governor and Councillors, 128 bombs were fired, some of which fell into the fort and started a fire. Most, however, fell close to the fort and against the palisades, while others exploded in the air, although it was the shrapnel from one of these which presumably fatally injured one defender and killed another.

Clearly the French were not making much progress, and it was insider information which eventually allowed them to identify Fort Nassau’s weaknesses and force a surrender. de Waterman told his employers that it was a man named Francois Tirol – no doubt the Swiss captured by Cassard – who had worked for the Van Peres at the fort two-and-a-half years earlier who played the role of informant and showed the French the paths behind the fort. This made possible the identification of a vantage point from which they could fire directly into it and destroy it.

It was for this reason, de Waterman told the Van Peres, that the Dutch were forced to seek a truce. After some preliminary negotiations between a Major in the French forces representing the Baron, and two Councillors from the Dutch side with Martinus van de Berge acting as translator, the Dutch were informed that de Mouans wanted to come into the fort to speak to the Commandeur (Governor) personally. He arrived about 10 o’clock in the morning with so many soldiers, that de Waterman raised objections, since that level of armed escort was not customary when negotiating. He was curtly told by de Mouans that the French were prepared to leave again and could force the Dutch with bombs, while the latter could not harm his forces at all.

de Waterman gave way, but then de Mouans demanded that the flag of the Prince of Orange be lowered from the fort and the French one hoisted. The Governor, however, objected strenuously, and said he could not permit anything like that, whereupon the Baron responded that those two flags simply could not tolerate one another, so the Dutch would have to take theirs down. If they did not do this, he said, then hostilities would begin again. The Prince’s flag consequently came down.

Negotiations

It was on 16th November that the two sides finally got down to negotiating the details of a ransom. The Baron demanded 600,000 guilders, but unlike Suriname, Berbice was an impecunious little colony and didn’t have anything like those kinds of resources. In the end, most of the sum which had to be paid, was handed over in the form of various kinds of property, such as gold and silverware, hogsheads of sugar, cargo goods, a barque and the like. In addition to these 261 enslaved Africans (including a small number of boys and a young child) found themselves transferred to French control.

The Africans would have been the silent spectators to this drama, and exactly what they thought about it all is, of course, not recorded. Whether any of them considered that in terms of two utterly unpalatable options it was better to go with the French than stay with the Dutch – or vice versa – or whether they didn’t care either way, will simply never be known. It is known that Cassard put in at Guadeloupe after his squadron left Suriname and Berbice, so it is more than likely that the Berbice Africans were sold there before he moved on to attack the Dutch island of Curaçao.

The ransom which was agreed by the two sides came to 300,000 guilders and 14 stivers (a stiver was a coin worth 1/20 of a guilder), in addition to which a blackmail sum of 10,000 guilders was paid over so the French would not pillage and raze the colony. A small part of this last sum, which was difficult to accumulate, was paid in what de Waterman described as “trifles” and “pots and pans.“ The problem for the Dutch was that they simply could not generate enough in cash or kind to meet the ransom, and so the solution the Governor and Councillors arrived at was to give the French a bill of exchange for 181,975 guilders and six stivers drawn on the Van Peres in the Netherlands. This bill was made payable to de Mouans on sight in six months time.

The French were not about to take the Dutch on trust as far as future payment was concerned, so they demanded that two Councillors go with them as hostages to ensure that the Van Peres met their financial obligations. The two who were sent as security were the youngest – Gerard de Veerman and Hendrik van Doorn. In their absence, the Governor assured the Van Peres, the plantations of Oosterhout and Vlissingen where they were managers would be under the supervision of their wives until their return. But they never did return. De Veerman died before the French squadron even left the West Indies, while van Doorn died after languishing for around a year and a half in a prison in Toulon, France.

In an attempt at a more upbeat conclusion to their letter, de Waterman and his Councillors reported that the French stationed in the fort did not take anything; they asked for what they wanted, although the Dutch had to supply them with provisions. In addition, 20-30 hogsheads of sugar still remained, and the fields “stand as beautiful as they have ever been.” The French, they wrote, had left Berbice at 9 o’clock in the evening of 8th December, 1712.

Bill of exchange

The French could not pursue the matter of redeeming the bill of exchange immediately, because there was still a war on and they would not be able to enter the Netherlands since it was enemy territory. Peace, however, was on the horizon, and the various documents coming under the rubric of the Treaty of Utrecht that marked the end to the Spanish Succession War, were finally signed in March and April 1713. With peace talks under way, the French investors wasted no time in presenting their bill of exchange to the patrons of Berbice.

If they thought their money would now be forthcoming, however, they were sorely mistaken; the brothers Abraham and Cornelis van Pere had absolutely no intention of honouring the bill. They said that Governor de Waterman had no authority to commit them to the payment of such a sum, and furthermore, the bill of exchange came to more than what the whole colony was worth. In their final salvo they said that in any case, it was much too high a figure in comparison to what Suriname had paid, and that colony was infinitely wealthier than Berbice.

Before the French decided to cut their losses, they made attempts to apply pressure to the Van Peres to force them to pay. The 19th century Dutch historian Netscher says that the French plenipotentiaries who were still in Utrecht in connection with the peace negotiations, attempted to get them to honour the bill of exchange, and the French Ambassador in The Hague, Viscount de Chateauneuf, tried to get the Dutch States-General (Parliament) to compel the Van Peres to pay up.

It was all to no avail, and on the 12th May, 1713, the Van Peres formally repudiated the bill of exchange, following which the Colony of Berbice and all its appurtenances came into the possession of a group of Marseilles ship-owners and merchants like an ordinary item of trade. But like a modern bank which finds itself in possession of a house because a mortgagee has failed to meet his mortgage payments, the investors really didn’t want the property; they wanted the money.

Redeeming the bill

The next move on the part of the French investors was to ask their attorney, Joseph Maillet, to try and see what he could retrieve from the situation. He was faced with the prospect of hawking the bill of exchange (effectively representing the Colony of Berbice) around Amsterdam, no doubt with the offer of a discount as an inducement to would-be purchasers. Maillet eventually did find some interested buyers in the form of a quartet of Dutch merchants – Nicolaas and Hendrik van Hoorn, Arnold Dix and Pieter Schuurman, and after some very protracted negotiations, the discounted sum of 108,000 guilders was settled on. The French investors ended up with a substantial proportion of their money, therefore, less almost seventy-four thousand guilders. As for the Van Peres, Cornelis, it seems, put up a quarter of the sum, so the family maintained its connection with the colony through a minority interest.

With all the relevant financial and other documents signed, therefore, on the 24th October, 1714 the Colony of Berbice passed officially out of the hands of a group of Marseilles merchants and into the hands of a group of Dutch merchants. They were to remain the owners of the colony until 1720, when a company was formed.