BEIRUT (Reuters) – As it spirals deeper into civil war, racked by violence, bombs and assassinations, Syria is led by an invisible president.

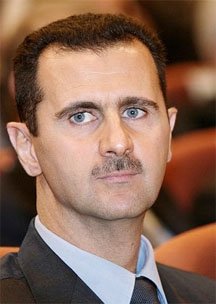

Since Bashar al-Assad addressed parliament in his last major public appearance in early June, rebels have taken their fight to overthrow him into Syria’s two main cities, seized swathes of countryside and assassinated four of his top security officials.

Faced with such devastating setbacks, many leaders – Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi springs to mind – would leap onto the public stage to reassure supporters they were still around, still in charge and ready to lead the fightback.

Instead, aside from two silent clips shown on television and a written message to his troops delivered on Wednesday, Assad has remained out of view for two weeks as the threat to his power and authority grows graver and ever more sustained.

His silence after the July 18 bombing which killed four of his inner circle, including his brother-in-law, has sparked rumours about his whereabouts and his grip on power – speculation which his opponents have been happy to fuel.

The United States says it does not know where Assad is, but “his control is slipping away, wherever he is”.

“We think it’s cowardly, quite frankly, to have a man who’s hiding out of sight, exhorting his armed forces to continue to slaughter the civilians of his own country,” State Department spokesman Patrick Ventrell said on Wednesday.

Lengthy spells of silence from the 46-year-old leader are nothing new. He took two weeks to respond when the uprising against his rule erupted in March last year and has made little more than a handful of significant appearances since then. But his latest retreat from view is odd in a time of acute crisis.

“Logic might demand that because of the uncertainties right now he would be more attentive to reassuring his adoring public – but that isn’t the logic that prevails here,” said a diplomat in Damascus.

In control

But the diplomat and analysts said Assad’s low profile did not mean he had lost control.

“By all accounts he is still a very central figure,” said Julien Barnes-Dacey of the European Council on Foreign Relations. “All the reports we have seen from people in the regime point to Assad having a hands-on grasp of what is happening.

“We have known for some time that this is a coterie of officials, many of them from his family, directing what is going on. But he is the arbiter, directing the crackdown,” he said.

The first sign that Assad was still in charge came when he appointed a new defence minister just four hours after the bombing of his top security officials. An ashen-looking Assad was later shown swearing in the minister – one of just two clips of the president shown on Syrian television since the bombing.

Since then he has reshuffled his security “crisis team” to replace slain officials and on Wednesday told his troops, in a message published by the armed forces magazine, that their battle with rebels would decide the fate of the country.

“The only focus of Assad’s attention at the moment is how to crush this uprising by military means,” said Barnes-Dacey, arguing that Assad may have clammed up simply because he had nothing to say to Syrians right now.

“Everyone knows on the ground that you are either with the regime or against it, and the fight will unfold on the battlefield rather than through the rhetoric.”

“Until the regime feels it has the upper hand, I don’t think we will see him again,” he said. “His style and personality is one that only engages, whether with his own people or the international community, from a position of strength.”

Security fears

If Assad is biding his time until he can announce better news, the stunning assassinations last month showed that even his close family, and by extension the president himself, are personally vulnerable to attack by emboldened rebels.

Knowing that a successful strike against him could deliver victory for rebels in a single blow, Assad will think long and hard about the risks of any public appearance.

He stayed away from the state funeral for his brother-in-law, and could be forced into the kind of seclusion endured by his Lebanese ally, Hezbollah leader Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah.

Nasrallah has barely appeared in public after going underground six years ago to avoid assassination by Israel after its month-long war with the Shi’ite militant group in 2006.

Assad’s silence contrasts starkly with the approach adopted by Gaddafi, who made frequent defiant speeches as Libya’s revolution closed in on him until his violent death last year.

“(The July 18 bombing) was a great psychological shock. It will take Assad time to regain his footing and his equilibrium,” said Fawaz Gerges, Director of the Middle East Centre at the London School of Economics.

But the speed with which he reassembled his team of close aides showed that “far from being a spent force, the security apparatus is still functioning”, Gerges said.

“You are going to see more violence and more massive force deployed in Aleppo for him to win the battle.”

His assessment of Assad’s unexpected steeliness echoes that of diplomats and Lebanese politicians who have followed the president’s response to the Syrian crisis throughout.

One Western diplomat in Beirut said an official who visited Assad recently reported that the president compared himself to a ship’s captain, vowing to stay at the helm in contrast to an Italian skipper accused in January of abandoning ship after steering it onto rocks off the Italian coast.

That defiance will ensure Assad is likely to keep fighting, long after his opponents believe that victory is in their grasp.

“I have no doubt in my mind he has proven much more resilient, stubborn, committed and much more prepared to win the battle of his life,” Gerges said. “I think even the Americans and Western European leaders are taking a second look at him.”

“All the analysis said that he is the soft type, without fire in his belly. He proved everyone wrong for the last 17 months.”