By Indra Khanna

Indra Khanna started curating contemporary visual arts projects in 2003, working either independently or in partnership with established institutions. She has set up exhibitions in public areas like parks and markets, as well as in galleries. She was a practising artist, community artist and art teacher for 15 years, during which time she married Hew Locke, before moving into curating. She has been an active member of grass roots artist’s groups, and for three years was a member of the London regional board of the Arts Council of England. From 2003 – 2010 Khanna was curator at Autograph ABP, where she worked on artists’ commissions, publications and exhibitions. She is currently working as co-guest artist/curator with Hew Locke on the Deptford X Festival.

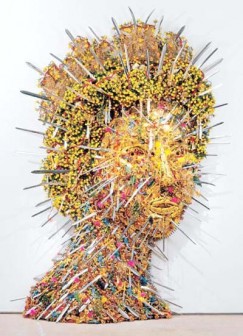

Artist Hew Locke was born and lives in the UK – but the texture of his life was formed by his childhood and teenage years spent growing up in Georgetown with his artist parents, Leila and Donald Locke. The colours and light of Guyana suffuse his work, and his crowded studio in south London is full of multi-coloured beads, fake foliage, ribbons, paints, model ships and plastic rubies.

Artist Hew Locke was born and lives in the UK – but the texture of his life was formed by his childhood and teenage years spent growing up in Georgetown with his artist parents, Leila and Donald Locke. The colours and light of Guyana suffuse his work, and his crowded studio in south London is full of multi-coloured beads, fake foliage, ribbons, paints, model ships and plastic rubies.

“A piece of work is only really complete when it gives me back a memory of Guyana – it could be a colour, a particular shade of green, a shape – memory is an elusive thing.”

Locke is fascinated by how different cultures invent themselves and select their symbols of nationhood. He is fascinated by Power – who had it, who has it and who desires it – and by how visual symbols, objects and styles are used to suggest or up-hold this grip on power.

Looking around you can see this interest in his huge range of art-works influenced by the coats-of-arms used by aristocrats, nations or indeed companies and corporations. Others draw from the official portraits in photography, paint or stone that leaders have commemorated themselves in across thousands of years. Just think of paintings of Elizabeth I – the Virgin Queen, the temple carvings of Egyptian Pharaohs, or photographs of Saddam Hussein posing with his gold-plated Kalashnikovs. Locke has spoken of the shock he felt as a teenager coming across the statue of Queen Victoria thrown down in the Botanical Gardens – and the equal shock on a more recent trip to Guyana to see it re-instated back on its original plinth outside the courthouse. He says

“Growing up in a post-colonial country, 1960’s and 70’s Guyana. I had Queen Elizabeth’s face on my school exercise books. I got into a lot of trouble for defacing them – giving them spectacles, moustaches. The standard thing you do as a kid.”

Even today, the glamour and power of Britannia is represented and recognised across the globe on stamps, coins and portraits, by an image of the Queen’s head. Locke is perhaps best known for his wall-based collaged reliefs of the Queen’s head. These can be up to eight feet high, and are covered in seething masses of plastic toys, fabric, flowers, animals, soldiers, each head giving a different atmosphere or telling a different story with its cast of little figures.

“My thinking of her is that she is somebody who has what? 60 years of secrets running around in her brain. That’s a tough thing. I wouldn’t want to know all the stuff I imagine she knows. Black Queen, for instance, was made at the start of the Iraq war out of a base of plastic M-16 machine guns. The guns then became a recurring theme in my work because we’re a nation at war and the Queen is the head of the army.

“In Demeter, she’s an earth goddess, so she’s covered in flowers; but then she’s also covered in dinosaurs, bunches of grapes. She’s got a scorpion and that’s attacking right in there. It’s a seething mass of stuff that is just, just holding together. Her eyes are in fear but can’t show it. There’s a shield up there.”

His sculptures and paintings of boats can be linked back to his criss-crossing of the Atlantic between Guyana and the UK as a child.

“I have been obsessed with boats for many years, and have a deep compulsion to make one every few years. For me they are symbols of the possibility of escape to some golden future. I remember two Rastafarian friends from school building a plywood boat under their house to sail back to Africa. They had no boat building experience at all – no matter what I said, they seemed to think that this was a real possibility. This boat would’ve killed them, but luckily it was never tried.”

On a trip to Portugal, he came across ex-voto ship models displayed in several churches, presented by sailors and captains as thanks to God for rescue at sea. This was one of the starting points for his beautiful and emotional recent installation in the church of St Mary’s and St Eanswythe in the port town of Folkestone.

Named For Those in Peril on the Sea, after the hymn Eternal Father, Strong to Save (often called The Royal Navy Hymn), he customized and hung from the ceiling seventy or so boats.

A fleet of dhows, barges, fishing boats, rafts, tankers, skiffs, junks, brigs, caiques, destroyers and lifeboats float above the aisle; vessels that serve trade, pleasure, plunder, escape, desperation, peace and war; their home port and final destination a mystery. It seems a piece he is especially proud of.

“It is a working church, and so services, weddings, christenings and all were held under the boats. People really took it to heart – coming into the church and just sitting and looking for a long time. Even the ladies who looked after the church started to make their own floral arrangements in model boats in the church.”

It’s easy to see why Hew’s work is usually popular with the public – it is figurative and decorative, and he is concerned to try and make things beautiful. Although some people have felt his work is insulting to the Queen, he has explained that he has no opinion of her as an individual human being, just a fascination in her as a symbol and image.

Others obviously share his interest, as he has exhibited across the UK, US and Europe, and his works are in the collections of the Tate Gallery, Brooklyn Museum and the British Museum.

Hew pulls out some of his newest works – beautifully engraved old share certificates from historical defunct companies that he researches and then paints onto. Share certificates are a window into the history and movement of money, power and ownership. He points out a certificate in a collector’s catalogue for the British Guiana Exploration Company, issued in Arizona in 1909.

“I‘ve got my eye on this one – it’s not easy to find Guyanese shares – I’m always looking for them.”

To find out more about these artists, see

http://www.hewlocke.net

http://www.indrakhanna.com