In both the Conventions of the Republican and Democratic parties there was no major focus on foreign policy. In fact, apart from John Kerry’s speech and that of Barack Obama, America’s relationship with the rest of the world was given short shrift. But a region like the English-speaking Caribbean has to measure the likely impact of the policies of any administration in Washington, as such policies are likely to have critical consequences for the foreign and domestic policies of the member states of the region. It is therefore worth examining the likely policies to be pursued by Obama if he gets a second term or those of a Romney administration, should the former Massachusetts Gover-nor succeed in unseating the first African-American President.

When it comes to the English speaking Caribbean, President Barack Obama has certain distinct advantages. His election in 2009 was widely acclaimed and he has remained very popular. His re-election is desired, if not expected. Seldom have I seen an American President who has so captured the hearts and imagination of Caribbean people as Barack Obama, with the possible exception of John Kennedy. I have noted, for example, that in a significant number of homes I have visited there are prominently displayed photographs of Obama, his wife and his children. But popularity is not policy.

In Obama’s first term the English-speaking Caribbean was treated as a sub-group of Latin America and the larger Caribbean region. As a consequence it was largely neglected. Obama continued his policy of forging ties with the large states of the region such as Brazil, Mexico, and Colombia. The smaller states, especially those of the anglophone Caribbean were neglected – or rather these states allowed themselves to be neglected. Contact between Obama’s administration and the member states of the Caribbean Com-munity was confined to the margins of such events as the Summit of the Americas in 2009. Neither the platform of the Democratic Party nor the pronouncements of Obama’s top advisers suggest that the English-speaking Caribbean will loom large in the policy considerations of a second Obama administration. It will be up to the Caribbean peoples and their governments to engage the administration in a meaningful dialogue on the array of problems facing the region. Only a regional foreign policy which is nimbly grounded in accurate analysis and implemented by our most skilled regional brains will make this possible.

On immigration, for example, there will be need for urgent policy decisions. Deportation of Caribbean citizens has been the bane of a number of societies. Yet in the Obama first term, despite representations, this policy has continued with evidently dire consequences as the stream of deportees swelled the ranks of criminals. And here one must lay the blame squarely at the feet of Caribbean governments. For when Obama used his presidential powers to prevent the deportation of Latin Ameri-can nationals there was no known effort on the partof Caribbean governments to have similar privileges extended to its citizens. The second time around there will have to be greater and more effective policy engagement. This will be true also in such areas as cooperation in the fields of climate change, security, educational training and, in particular, exchanges in the field of technology which can help transform Carib-bean economies with a view to reducing the unacceptably high levels of unemployment. In the final analysis the anglophone Caribbean will have to craft a coordinated policy with which to engage a new Obama administration across a wide variety of issues important to the region.

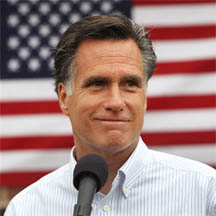

The Demo-cratic platform at least makes reference to the Latin Ameri-can and Caribbean region in terms of criminal activities, drug trafficking and terrorism. The Republican platform does not accord any noted importance to the region. But the most troubling aspect of Mitt Romney and the Republicans’ pool of foreign policy advisers is that it is dominated by many of the neo-cons who advised George Bush. The doctrine common to all of them is the belief that military power is more important than diplomacy. Mitt Romney himself has declared that he will rely on military power to pursue America’s national interests. This doctrine should cause Caribbean leaders some degree of concern. It was a similar doctrine that persuaded President Reagan to invade Grenada in 1983 and provoked deep-seated divisions among member states of the Caribbean Com-munity which has lasted to this day. Everything suggests that a Romney administration will pose major problems for the region from cuts in foreign aid to an unhelpful attitude on such critical matters as climate change. This being the case the leaders of the region should have long since been preparing for the outcome of the US presidential elections. There is no evidence that they are engaged in activities of this kind.

Such intellectual lassitude is regrettable. One particular factor should redound to the advantage of the small states of the English-speaking Caribbean region. After ten years of war which has drained America of much treasure and life, there is a discernable tendency on the part of the population to disdain further military adventures. Some commentators believe that more Americans think that diplomacy is the option to pursue as America turns inward and seeks to grapple with the ravages of the financial crisis of 2008 and its massive fiscal problems. My own view is that these circumstances provide the English-speaking Caribbean with an excellent opportunity to design the kind of policies which facilitate the realization of its core interests and objectives.