Everything on earth is changing – bit by bit – right now – in front of our very eyes. In two or three hundred years . . .there will be a new world, a better world. We can plan for it, work toward it, and suffer for its sake. We’re creating it – that’s the whole point of our existence – our so-called happiness.

There’s no such thing as happiness . . . it doesn’t exist. All we can do is work, suffer and go on working – happiness belongs to the future, to the unborn.. . .

We only long for it.

(Vershinin, in Chekhov’s Three Sisters)

One of the most highly acclaimed plays on the contemporary stage at present opened at The Young Vic in London on September 8, 2012. It is one of the great classics, Anton Chekhov’s Three Sisters adapted in a version by Australian director Benedict Andrews. This is a truly remarkable production which makes an important statement about modern theatre. It is a play by one of the major modern dramatists, adapted in a new version by a leading contemporary director, in a mainstream theatre that bridges the old and the new, presenting a drama that pronounces upon change. It is an excellent illustration of not only the tragic human condition, but the state of drama itself in the wider world.

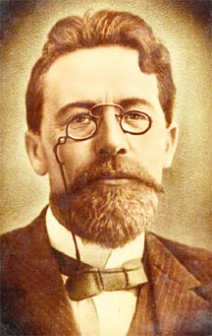

Anton Chekhov (1860-1904) was a Russian medical doctor who first turned to writing short stories to support his family, but became the greatest Russian writer of his time in the generation after Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. He also became one of the most renowned modern playwrights. He wrote at a time when the western theatre had just changed from the Classical influence to Naturalism which believed in the direct reflection of the realities of the society in drama (and fiction). The styles and devices of plays changed in order to better deal with social changes, and modern drama developed. But Chekhov, while writing within this (new) theatre, was himself ahead of his time with his themes as well as his use of other devices which would then become important on the stage later on.

For example, he dramatised the decline of the aristocracy and the rise of a new (middle) class in The Cherry Orchard dealing with the end of serfdom and feudalism in a quite Marxist way some 15 years before the Marxist-Leninist Revolution in Russia in 1917. The play seemed somewhat prophetic in this, but it also brought in styles which pushed dramatic realism forward. The Young Vic’s notes on Three Sisters mention his invention of “surface naturalism with strong undertones of expressionism and vaudeville” which is also strong in Cherry Orchard. But more significant is the way he advanced these in a form of performance that critics began to write about only after Samuel Becket and the 1950s. That is his invention of the Theatre of the Absurd or Absurdism.

For example, he dramatised the decline of the aristocracy and the rise of a new (middle) class in The Cherry Orchard dealing with the end of serfdom and feudalism in a quite Marxist way some 15 years before the Marxist-Leninist Revolution in Russia in 1917. The play seemed somewhat prophetic in this, but it also brought in styles which pushed dramatic realism forward. The Young Vic’s notes on Three Sisters mention his invention of “surface naturalism with strong undertones of expressionism and vaudeville” which is also strong in Cherry Orchard. But more significant is the way he advanced these in a form of performance that critics began to write about only after Samuel Becket and the 1950s. That is his invention of the Theatre of the Absurd or Absurdism.

Three Sisters is another of the classics in the form of a modern tragedy in the drama of that time. Three daughters and the son of a prominent military general of the Russian army fail to progress and in fact suffer first a state of inertia, then a decline following the death of their father. They entertain an obsessive hope of returning to live in Moscow and generally find happiness which becomes elusive, and gradually move to an end in disappointment and tragic circumstances. The sisters see the fragmentation of the family and its grand tradition after their brother squanders the family fortune, they fail to go to Moscow and each fails to achieve the happiness and fulfilment they seek. The lines from the play quoted above reflect the illusion pervasive in the tragic human condition, the uncertainty in the future, the stasis, meaninglessness and disaster. It also dramatises the fall of the aristocracy in the face of their decadence, class biases and wastefulness. Yet, just as in Cherry Orchard, there is an undercurrent question about a sense of loss in the passing of an age of tradition and grandeur.

Performing this play in a theatre like The Young Vic is another factor. The Old Vic is one of the major theatres in the strong tradition of the post-Victorian era, and the newer house named itself in deference to its older and distinguished neighbour. But while carrying on the conventions, it is designed to allow innovation, experimentation and the many current forms that directors might want to pursue in modernist theatre. It is a bridge between the older classic traditions and the contemporary possibilities.

Benedict Andrews takes full advantage of this, making use of several modernistic devices and styles. His production is faithful to Chekhov. Rather than a brand new interpretation, his innovative techniques are used to sharpen and elucidate Chekhov’s meaning. The first of these is the language whose translation from the original Russian is further adjusted to a realistic 21st century speech including slang, colloquialisms and expletives. To intensify its immediacy, it also uses present-day reference points which place the action in a familiar present-day time. The play is about time and the passing of an age. But while it dramatises some of the reasons for the fall of a decadent, wasteful, deceptive aristocratic class, it does not suggest that the scenario which the age is changing to, is better. One of the sisters (Masha) has cause to remark, “If we don’t have a clue why we’re here then life is just … empty … just…empty nothingness.” In other instances the speech is lively, racy and reflects the contemporary directionless or even desperate generation.

The Theatre of the Absurd, including the vaudeville elements, was the strongest area of emphasis in the performance styles, taking in characterisation, body language and speech. These were employed to magnify many dramatic situations as well as the condition of the characters in their tragic states. Sometimes there were characters given idiosyncratic traits, or expressions used to make particular behaviours or attitudes look ridiculous. Some characters played in exaggerated overtones while there were many instances of deliberate humour (the vaudeville mentioned) employed as devices for commentary.

These were accompanied by carefully crafted choreography, sound, stage use, or rather the use of space, and symbol. In the play there is a constant progression to fragmentation and displacement. At the end of Act Two the frustration of the sisters becomes a bit unbearable and in this production it closed with a loud vocal expression of the obsessive need to move away and return to Moscow. This cry was echoed from the top of a pinnacle, painstakingly built piece by piece by the youngest sister. Following this, however, the plans to reach the capital city went nowhere, while the home was falling apart. This was reflected in the equally painstaking dismantling of the entire set piece by piece until the stage was bare for the final scene, which reflected the total emptiness of the sisters’ lives by the time the play came to an end. All set changes were done by the actors as part of the action which might suggest how the characters were also the engineers of their own fate.

The human condition analysed by Chekhov at the turn of the 20th century has not changed. The play Three Sisters, which makes a statement about stasis in mankind’s vain effort to progress in Chekhov’s time, is replayed with a 21st century setting and techniques to say the same thing about mankind 100 years later. Another disturbing issue for the sisters is the fact that aristocrats did not work for a living, and to fill some of the emptiness, two of them assiduously pursue work. Andrews’ production used that same detail of plot to put a stress on the Freudian principle of the need for work to achieve reward as a driving sub-conscious force in man. It communicated futility among characters in the play.

In Chekhov’s time theatre had changed; modern drama had evolved and today it has progressed in several directions through modernism to post-modernism. Chekhov was an innovator, extending the frontiers with his use of Absurdism among other forms of realism. Andrews has made Chekhov alive again in an innovative production which is at the cutting edge of contemporary theatre. The human condition in the year 2012 is tragic and going nowhere in a quest for happiness and fulfilment. Andrews wishes to tell us that, and goes into a new version of an old theatre and a contemporary translation of an old classic drama in order to make that statement. In so doing he has made a further statement about the theatre today.