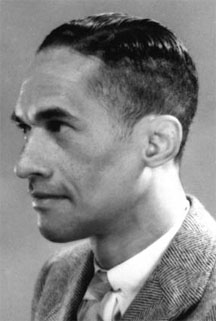

Edgar Mittelholzer (1909-1965) is a major Guyanese writer. Not only is he one of the most recognized Guyanese writers, but the nation accords him a most distinguished place in its literature and heritage. He is regarded with some awe arising from the power and character of his fiction, but also because of his association with the country’s older colonial heritage, with the supernatural, and with writing as a career/profession. This recognition is demonstrated by the establishment of the Edgar Mittelholzer Lecture Series presented annually by the Department of Culture. The 2012 Distinguished Lecture will be presented this week on Thursday, November 29 in Georgetown.

This series, which was started by AJ Seymour in the 1970s, faded away for many years before being recalled to life by the Director of Culture James Rose. The Wednesday lecture will be given by famous Guyanese novelist and fiction writer Pauline Melville at the Umana Yana at 5.30 pm. Melville won a Commonwealth Writers Prize with a collection of short stories Shape-Shifter in 1991. Her The Ventriloquist’s Tale won the Guyana Prize for Literature as well as the Whitbread Prize for a First Novel in 1998. Her latest novel is Eating Air.

Many of Mittelholzer’s achievements, characteristics and preoccupations justify the hallowed place he holds in the nation’s literary hierarchy. He is distinguished and made identifiable by many factors, some of which are tied to his roots in colonial New Amsterdam. He wrote fiction – novels and short stories, as well as a number of poems. For a while he practised his craft in his native town before moving on to Georgetown and then Trinidad before eventually settling in England. His activities at home in the 1930s left something of a mythology behind him that remains to intrigue readers today.

There is hardly a visible remnant left in Berbice to mark his existence. The house where he lived is no longer there. An empty lot is all that is left to identify the place where it stood on Coburg Street; the plot is picturesque, neatly surrounded by a wooden picket fence and populated by well-kept vegetation and flowers. The story goes that the house was deliberately dismantled in the midst of some family dispute. One has to go inside the home of one remaining relative in the suburbs just outside of Tucber Park to find a relic. They unassumingly point out an old four-poster bed in a small bedroom where Edgar used to sleep when he resided there for a while.

There is hardly a visible remnant left in Berbice to mark his existence. The house where he lived is no longer there. An empty lot is all that is left to identify the place where it stood on Coburg Street; the plot is picturesque, neatly surrounded by a wooden picket fence and populated by well-kept vegetation and flowers. The story goes that the house was deliberately dismantled in the midst of some family dispute. One has to go inside the home of one remaining relative in the suburbs just outside of Tucber Park to find a relic. They unassumingly point out an old four-poster bed in a small bedroom where Edgar used to sleep when he resided there for a while.

However, New Amsterdam is recognised in everyone’s consciousness in Guyana as Mittelholzer’s home town, and the aura that still envelops the locality is always associated with him. Furthermore, as mentioned above, he has left behind something of a mythology attached to his idiosyncracies, his writings and his preoccupations. Foremost among these is his fabled determination to be a writer and to live by his writing; how he walked from door to door selling his short stories; how he endured years measured by recurring cycles of rejection slips from publishers to whom he had submitted his manuscripts. Even the time he spent in Georgetown was really a waiting period in his undaunted quest to be a professional writer. This focused career characterized the way he ordered his life ever after.

A part of it is also his documentation of the colonial society in Berbice, its obsession with class, colour and race, and the way the society has been looked upon, as if defined by his fiction and his biographical work. By far the most indelible impression is to be found in the novel My Bones and My Flute, which some critics believe is his best. Indeed, it fictionalises both colonial New Amsterdam and the upper reaches of the Berbice River in such memorable fashion that the book stands as a record of the place. It recalls the mythical spiritual preoccupations with the Dutch, the forest and riverain environments that they haunt and the supernatural mysteries that still dwell in a society with a deep respect for obeah. The New Amsterdam and Berbice River that colour the imagination are the New Amsterdam and Berbice of Mittelholzer’s My Bones And My Flute.

Added to that are the repeated portraits of the artist that recur in his fiction. It is the symbolist figure of the artist as intellectual and rebel that was first created in his fictionalisation of New Amsterdam. It is a progressive force in a conservative society which served him in other capacities later on. However, there are yet other factors of great importance that give Mittelholzer his lofty, hallowed place in Guyanese literature. One is the creation of social realism in Guyanese fiction. Novels of realism in the Caribbean led by HG de Lisser in Jamaica before 1920, had already paved the way, followed by the Trinidadian fiction led by CLR James and the ‘Beacon‘ writers in the 1930s. But it was advanced by Mittelholzer in Guyana in a major way first with Corentyne Thunder finally accepted by a publisher in 1941 after having been written in 1938. This was the first novel in local literature to delve into the village life of East Indian peasants in British Guiana. It was the kind of East Indian literature, written by a non-Indian, that was not to be approached by Indian writers for decades to come. Unlike what had been done earlier by such poets as the Ruhoman brothers and Ramcharitar-Lalla, it probed local Indian life in the manner of social realism.

Another outstanding novel of this nature produced by Mittelholzer was The Life And Death of Sylvia, a novel of colonial Georgetown. This was another deep study of the colony in its urban environment, beleaguered by the effects of class and race, but this time also with a treatment of economics, the position of the woman among other gender issues, and treachery. Mittelholzer indulges in a tendency to explore sexuality in fiction, as he does too in this work. Also found in it is his continued preoccupation with art and artistry, this time also with music, which critic Juanita Cox finds is important to his craft. It is the tragic tale of its heroine, Sylvia, and a revelation of the nature of Georgetown society – another of this writer’s forwarding of social realism in Guyanese fiction.

His tragic sense may be found in short stories and a very little known novella. In the story We Know Not Whom To Mourn, there is the irony of a dying man lying upstairs while his relatives prepare to mourn what seems to be the inevitable. Almost miraculously, he recovers. But unnoticed by all, the apparently quite healthy cousin who had been reclining in a chair downstairs is found dead with a bottle of poison lying next to his hand. The novella is The Adding Machine, about an estate owner who commits atrocity after atrocity against villagers and others while he accumulates wealth. He acquires an adding machine to calculate his earnings, but it turns out to have mysterious powers. Each time he commits a wrong, and punches in figures on the machine, a physical blemish appears on his skin. This continues until he is totally corrupted and consumed by the machine.

It has already been said that a part of the Mittelholzer mythology represents elements of his literary life. He was a member of circles that met occasionally to discuss literature, culture and philosophy and compare creative work. Such sessions were known to flourish around Martin Carter in the fifties and sixties, but clearly they were going on long before him. The evidence is found in the immortalizing of such sessions by Mittelholzer in his poem ‘Meditations of A Man Slightly Drunk.‘ The slightly satirical poem stresses the constant flow of rum that seems to have been the main part of the literary sessions.

For these attributes, creations, documentations and achievements, the nation of Guyana honours Edgar Mittelholzer again with the Distinguished Lecture by another celebrated fiction writer, Pauline Melville.