Following, but not as a result of last week’s column addressing the parlous state to which Cabinet Secretary Dr Roger Luncheon has brought the National Insurance Scheme, I had two very interesting conversations, one with a business leader and the other with an MP. In advance of consultations to be held with the actuary on his draft report on the eighth five-yearly actuarial report on the NIS, they both wanted to know my thoughts on the report’s findings and recommendations. Both seemed not to be in the least bit uncomfortable to admit that while they had last week’s Sunday Stabroek they did not get around to reading the newspaper or the full-page column on precisely that topic. We can only guess about their contribution to a consultation for which they would have been so hopelessly unprepared on a matter of such grave national importance, a matter that has been the subject of several articles over a recent two-week period.

It is even worse. By now we all should have been aware that the government of which Dr Roger Luncheon is the Cabinet Secretary and the Board of the NIS of which he is the Chairman, did not implement the recommendations contained in the sixth and the seventh actuarial reports on the Scheme at December 31, 2001 and 2006. But the two persons I spoke with apparently did not know about the parlous state of the Scheme, while my politician friend was bold enough to ask seriously but rhetorically, how did we “allow that?” Perhaps our politicians have been reading too much Lewis Carroll.

A second issue on the NIS is the location of the consultation. Now you would expect that anyone consulting with the actuary would want to meet with him outside of the framework of the NIS Board or its chairman. But that kind of liberal and rational thinking would in Dr Luncheon’s eyes be too dangerous. The consultation had to take place with Dr Luncheon, whose leadership of the Scheme is not insignificantly responsible for its parlous state, at Luncheon’s office and under his chairmanship. Dr Luncheon may strike many as a bumbling incompetent but he remains a dangerous practitioner of artful politics. The idea to hold the consultations on his turf and in his presence was clearly designed to control any criticisms of his government’s abominable management of the Scheme, now facing its worst crisis in 42 years.

A second issue on the NIS is the location of the consultation. Now you would expect that anyone consulting with the actuary would want to meet with him outside of the framework of the NIS Board or its chairman. But that kind of liberal and rational thinking would in Dr Luncheon’s eyes be too dangerous. The consultation had to take place with Dr Luncheon, whose leadership of the Scheme is not insignificantly responsible for its parlous state, at Luncheon’s office and under his chairmanship. Dr Luncheon may strike many as a bumbling incompetent but he remains a dangerous practitioner of artful politics. The idea to hold the consultations on his turf and in his presence was clearly designed to control any criticisms of his government’s abominable management of the Scheme, now facing its worst crisis in 42 years.

Even as we ponder the serious medicine prescribed by the actuary to address the crisis the NIS faces, my hope is that the media would now ask the private sector as well as the political parties and the trade unions in particular, for a report on the consultations. As I indicated last week, I am particularly concerned that if the recommendations are accepted the burden of the adjustments would be felt mainly by the workers of the country.

Now you see it, now you don’t

Today’s subject seeks to raise questions on other matters we may not have noticed. It touches on the disproportionate sharing of the benefits and burdens of the taxation system and the inequality it has spawned in the vast disparity of wealth among those who are part of the power structure and those outside of it. This column has addressed such disparity time and time again and for emphasis captioned a column on January 29 of this year drawing attention to the US system under the topic, “If Mitt Romney was in Guyana, his 13.9% tax rate would have been lower.” The reason is that our tax system favours the employers, those with capital over the workers, who often struggle to make ends meet and who at the end of their working lives which the actuary now says should be extended to sixty-five have nothing but an NIS pension to look forward to. I will deal with that disproportionality next week and look at how different types of income are taxed differently in Guyana.

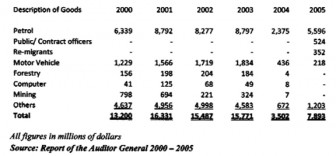

For starters, let us look at the system of remission of duties granted by the government which was reported on each year in the annual report of the Auditor General up to 2005.

There is a lot to argue with on whether some of the figures do not defy the logic of the reported performance of the economy during the six years. The wild swings between 2003 and 2005 seem to make little sense, but that is really not relevant here, except perhaps to reflect the quality of some elements of the work done by the Audit Office. As for the revenues of the country and their impact on the resources available to spend on education, health, security and infrastructure, it matters little whether the authority to grant remission of duties since 2003 is vested solely in the Commissioner General as the Audit Office seems to think.

But even if the Audit Office is correct, and regardless of where the range of authority lies, there should surely be some formal manner in which the body vested with the powers of remission reports to taxpayers and the National Assembly on the extent and value of remissions granted. If the power is vested in someone else, the one person who should insist on the publication of the information is the Minister of Finance who has constitutional responsibility for the national budget. Any taxes required to meet public expenditure which are borne, if at all, at lower effective rates by one segment of the population, must inevitably be met by those who do pay. But coincidentally or otherwise, the Audit Office ceased to report on remissions from the time Dr Ashni Singh became Finance Minister.

Dr Singh and tax remissions

Dr Singh has been egregiously reckless on the expenditure side of the Budget, misdirecting public funds to NICIL of which he is the Chairman, making unlawful withdrawals from the Contingencies Fund for which he is solely responsible, and authorising the transfer of billions of dollars from the 2000 series bank accounts which requires statutory authority. Under the Jagdeo presidency – and quite possibly still – spending outside of the authority of an Appropriation Act became normal with not even a hint of protest from the Finance Minister. After his role in the unlawful granting of concessions to the former President’s friend, it is difficult for anyone to believe that he is any less careless with the country’s tax revenues than he is with its expenditure.

Yet, our laws give the Minister of Finance enormous powers to give away tax revenues, over what may appear to be a small range of taxes but which have substantial fiscal implications. We start with the first and perhaps best known concession, the tax holiday. Under the Income Tax (In Aid of Industry) Act, the Minister of Finance has discretionary powers to grant an exemption from corporation tax with respect to income from new economic activity of a developmental and risk-bearing nature, or from dozens of economic activities. Without putting too much of an emphasis on it, the ease with which Mr Jagdeo and Dr Singh amended the law for friends shows how elastic and discretionary the law is.

And bear in mind that in approving tax holidays, the Minister is also extending exemptions from Property Tax and the Capital Gains Tax act.

Here again there is a silence feeding the appetite of the conspiracy theorists. Tax holidays can extend from five to ten years and cost billions. So the law requires some accountability. Under the Investment Act the Audit Office is required to carry out annual audits of the tax holiday incentives granted by the Minister, but the Audit Office has failed in its obligations under section 38 of the Investment Act to have laid in the National Assembly such a report for any year. The deadline for this is six months after the end of each financial year.

I have repeatedly raised this omission with no reaction from anyone. Surely the Public Accounts Committee has a duty to deal with this blatant disregard for the law with the potential of massive cover-up of tax giveaways. All to the detriment of those who pay taxes.

To be continued