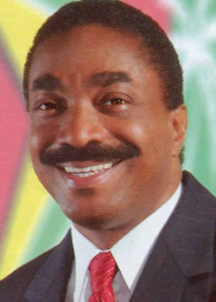

Ruling on one of several battles between the executive and the legislature, acting Chief Justice Ian Chang yesterday found that Minister of Home Affairs Clement Rohee as an elected member has a right to speak in the National Assembly although it does not appear to be enforceable by the court.

The ruling it seems would leave the question of Rohee’s speaking to the Speaker of the National Assembly and the procedures of the House.

“… it is the view of this court that Mr. Rohee’s right to speak in the National Assembly derives from his office as a member of the National Assembly and not from his office as an executive Minister. This, his right as an elected member of the National Assembly must be concomitant with his constitutional duty to speak for and to represent his electors in the National Assembly who, in turn, have a concomitant right to be represented,” the Chief Justice said in his thirty-four page ruling yesterday.

The CJ pointed out that Article 9 of the Constitution expressly states that “Sovereignty belongs to the people, who exercise it through their representatives….”

He later noted that it is irrelevant for the purpose of the case that Rohee holds the portfolio of Minister of Home Affairs since it is on the basis of his office as a member of the National Assembly and not on the basis of his office as minister that he derived the right or privilege to speak in the Assembly.

In concluding his ruling, Justice Chang pointed out that Attorney General Anil Nandlall in his affidavit in support of the motion that Rohee should be permitted to speak alleged that Rohee was “gagged” by the Speaker of the National Assembly and may be further gagged not for conduct inimical to the National Assembly but because of the no-confidence of the majority of members in him as the Minister of Home Affairs.

Justice Chang said “in such an exceptional state of affairs in the National Assembly, the need for the court to intervene in the processes of the National Assembly does appear to arise in protection of his constitutional right as an elected member of the National Assembly”.

However, in what will be seen as a nod to the separation of powers between the judiciary and the legislature, Justice Chang said that even though the court has the jurisdiction to inquire into the conduct of the Speaker and the National Assembly to ascertain whether either had acted unconstitutionally or illegally “it is no part of the court’s function to give directions to the Speaker or the National Assembly as to the future conduct of the Assembly’s affairs”.

Justice Chang posed the question that if the court were to grant the directive order sought by Nandlall and the Speaker were to disobey, whether the Attorney General could file a motion for the Speaker to be committed to prison or punished for contempt? I think not, was Justice Chang’s terse answer and he quoted in support the ruling of Lord Coleridge CJ in Bradlaugh v Gossett (1884) that “The history of England and the resolutions of the House of Commons itself show that now and then injustice has been done by the House to individual members of it. But the remedy, if remedy lie, lies not in actions in the courts of law but by an appeal to the constituencies whom the House of Commons represents.”

He also cited the Rost V Edwards (1990) ruling which said in part “The Courts must always be sensitive to the rights and privileges of Parliament and the constitutional importance of Parliament retaining control over its own proceedings.”

‘Unenforceable by the court’

Justice Chang then said that assuming that the court on the evidence were to find in Nandlall’s motion that Speaker did act in violation of Rohee’s constitutional right as an elected member of the National Assembly and that of his electors “it behoves the Speaker and indeed the National Assembly as a whole to respect not only the finding of the court for reason of its finality but also the constitutional right of Mr Rohee to represent his electors and their constitutional right to be represented by him in the National Assembly. But, neither the constitutional right of Mr Rohee to represent nor that of his electors to be represented in the National Assembly is an enforceable constitutional right under Article 138 to 151 of the Constitution”.

He then went on to say “Thus, even though the issue as to whether Mr Rohee as an elected member of the National Assembly has a constitutional right to speak in the National Assembly (irrespective of the expression of no confidence in him as Minister of Home Affairs) is justiciable, the right itself (assuming it exists) appears to be of such a nature as to be unenforceable by the court.”

Justice Chang then struck out the majority of Nandlall’s motion retaining only his contention that prohibiting Rohee from speaking and not recognizing him for the purpose of presenting bills, motions etc “is unlawful, unconstitutional, ultra vires, in excess of and without jurisdiction, contrary to the rules of natural justice, arbitrary, capricious, null and void and of no legal effect”.

The CJ threw out the key directive order sought by Nandlall that an order be made by the court directing Trotman to allow Rohee to perform his functions.

The Chief Justice then noted that though these were interlocutory proceedings, the court had found it fit and necessary to make “final and definitive” pronouncements on questions of law that may have the effect of making it unnecessary for the parties to proceed to a hearing of Nandlall’s substantive motion. The Chief Justice’s ruling yesterday pertained to a summons by Opposition Leader David Granger to strike out the motion of the Attorney General.

Justice Chang’s ruling came following a challenge by Nandlall of Speaker Trotman’s decision last November which had limited Rohee’s participation in Parliament pending the findings of the Committee of Privileges on the enforceability of a motion in the name of Opposition Leader Granger seeking to have Rohee gagged in the National Assembly.

Trotman, who had all times made it clear that Rohee could have spoken in the Assembly as an elected member but not to represent the Ministry of Home Affairs in any way, had said he would take no further action on the move to sanction the minister until the courts ruled on Nandlall’s action. CJ Chang’s ruling now appears to clear the way for Trotman to act.

In the action, which had named both Trotman and Granger as respondents, Nandlall had asked for a declaration that the Speaker’s decision is “unlawful, unconstitutional, ultra vires, in excess of and without jurisdiction, contrary to the rules of natural justice, arbitrary, capricious, null and void and of no effect.” This was one of the remedies sought by Nandlall that was ignored by the CJ.

Following his almost one-hour ruling there appeared to be some confusion among even the lawyers present as to what the ruling meant and it saw Nandlall asking Justice Chang in court, after he would have left the bench, whether the minister can speak in Parliament. “As a matter of pure law he cannot be prevented from speaking and this is final,” the Chief Justice said.

However, attorney-at-law Basil Williams, who represented Granger in court, argued outside of court that the judge had not ruled on the minister’s right to speak as the issue is still to be argued when the matter is heard substantively with relation to paragraphs 1(b) and 3(b) of Nandlall’s motion.

‘Well established’

On another issue, Justice Chang said it is a well-established constitutional principle firmly rooted in the soil of the doctrine of separation of powers that the court has no jurisdiction to judicially review the workings or operations of the National Assembly except for the purpose of determining whether the National Assembly had acted unconstitutionally or contrary to law. He said that a Motion to judicially review the conduct of the National Assembly must be premised on a claim of unconstitutional or illegal conduct on the part of the National Assembly.

Granger had moved to have the Motion struck out on the grounds of no jurisdiction based on the contents of the affidavit in support of the Motion but Justice Chang said that the no-jurisdiction issue can be raised only on the contents of the Motion paper not the affidavit in support of the motion.

Among other issues Justice Chang said the court noted that what was referred to the Privileges Committee by Speaker Trotman for its determination and/or advice and/or report involves a question of law. While the court see nothing wrong with the committee being asked to answer a legal question on referral, the CJ said that the court was the final arbiter on all legal questions.

“There is no legal prohibition against any person, body or authority (including the Privileges Committee) pronouncing on questions of law even though such person, body or authority cannot speak finally on such an issue. Only the court can speak with finality on a legal question or issue,” Justice Chang said.

However, since the referral by Speaker Trotman to the Privileges Committee is not prohibited by any provision of the Constitution or the law, the CJ struck out the relief sought by Nandlall in this regard.

Throughout his ruling the CJ debunked the notion forwarded by Nandlall that Rohee’s status as Minister of Home Affairs was relevant to the speech argument. Said the CJ: “His status of Minister of Home Affairs has no legal relevance for the purposes of this case since the issue of his being silenced in any way has nothing to do with his office as Minister of Home Affairs, the tenure of which per se does not at all give rise to any right or privilege to speak in the National Assembly”.

On the question of whether Trotman could prohibit Rohee from speaking or making a presentation the CJ said “It is indeed difficult to see how, in the face of the doctrine of separation of powers, the Speaker can prohibit a member (particularly an elected member) from speaking or making a presentation in (the) Assembly in the account of the absence of confidence of the majority of the members of the Assembly in that person qua an executive Minister when he sits in the Assembly not qua Minister of the Government but qua member of the National Assembly”.

The motion filed by Nandlall was his fourth on behalf of the government and had its genesis in the ruling made by the Speaker, which limits Rohee’s participation in the House, pending the findings of the Committee of Privileges on the enforceability of a motion brought by Granger, which seeks to have Rohee gagged in the National Assembly.