Conclusion

Today I return to and conclude the topic started on December 16, 2012 to mark the 20 year anniversary of Business Page. I chose the banking sector to mark the occasion because that sector was in the inaugural column, and I thought it would be useful to see how the sector had performed over the two decades. Twenty years ago the Government played a big role in the banking and financial sectors in Guyana. It owned and operated the Guyana National Co-operative Bank (GNCB) and also had major interests in the National Bank of Industry and Commerce and the Guyana Bank for Trade and Industry (GBTI). The only other commercial banks operating in Guyana twenty years ago were the Bank of Baroda Ltd, an Indian-owned multinational, and a branch of the Canadian-owned Bank of Nova Scotia. Other players in the financial sector were the Guyana Co-operative Agricultural Development Bank (GAIBANK) and the Guyana Co-operative Mortgage Finance Bank (GCFS), both wholly-owned Government entities, and the New Building Society Limited.

Twenty years later the government is completely out of commercial banking, GNCB and GAIBANK are no more in existence or operational while two new domestic banks are closing in on their own twenty years of operation. In other words, there is only one additional operator in the commercial banking sector and no new international bank in the twenty years since 1992. The ownership structure is one of concentration and control with one of the international banks (Scotiabank) still operating as a branch and the other (Baroda) a wholly owned subsidiary. RBL, GBTI and Citizens Bank are all subsidiaries with a majority shareholder, while DBL’s ownership structure is somewhat more complex, with its annual report disclosing that there is no shareholder whose interest exceeds 5% but whose annual general meeting, among the commercial banks, is probably attended by the least number of members.

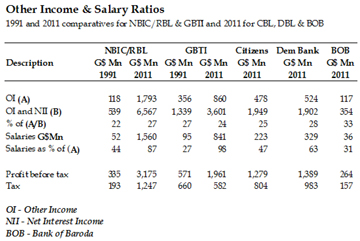

In the tables in today’s column we see that those banks have all done extremely well, surpassing the growth in the economy many times over. Let us take profits before tax. From nothing the Demerara Bank Limited and Citizens Bank Limited recorded pre-tax profits in 2011 of $1,279 million and $1,389 million respectively; the National Bank of Industry and Commerce which was renamed the Republic Bank (Guyana) Limited and acquired the operations, liabilities and certain assets of the GNCB has seen its pre-tax profits increase from $335 million in 1991 to $3,175 million in 2011, an increase of 847% while the GBTI which reported pre-tax profits of $571 million in 1991 saw those profits rising to $1,961 million in 2011, an increase of 243%. The performance of the Bank of Nova Scotia was no doubt equally impressive although under then prevailing laws that branch was not required to report on the performance of its domestic operations.

In the tables in today’s column we see that those banks have all done extremely well, surpassing the growth in the economy many times over. Let us take profits before tax. From nothing the Demerara Bank Limited and Citizens Bank Limited recorded pre-tax profits in 2011 of $1,279 million and $1,389 million respectively; the National Bank of Industry and Commerce which was renamed the Republic Bank (Guyana) Limited and acquired the operations, liabilities and certain assets of the GNCB has seen its pre-tax profits increase from $335 million in 1991 to $3,175 million in 2011, an increase of 847% while the GBTI which reported pre-tax profits of $571 million in 1991 saw those profits rising to $1,961 million in 2011, an increase of 243%. The performance of the Bank of Nova Scotia was no doubt equally impressive although under then prevailing laws that branch was not required to report on the performance of its domestic operations.

While the growth of the economy, inflation and the scale of their services would have contributed to the increased profitability of the banks, they would inevitably have benefited from the barriers to entry in the sector with the government very reluctant to grant further banking licences. There is no study of which I am aware into the operations of the sector to examine the effects on the economy, beyond some fierce competition for market share, which the concentration of ownership can facilitate.

This kind of research which goes well beyond a newspaper column, is what one should expect from the Bank of Guyana and the University of Guyana, and it would be helpful for a better understanding of the sector and the formulation of policy initiatives if such a study, or indeed studies were undertaken.

What is clear, however, is that while in the years immediately following 1992, it was almost obligatory for the Minister of Finance to comment critically on the high spread between the rates of interest charged on loans and advances and those paid on deposits, that no longer happens. Moreover with a number of the banks taking up membership of the Private Sector Commission the question of spreads seems completely off the table.

The following two tables show some indicators in the landscape in which the commercial banks have operated. Inflation has declined dramatically; the banks’ prime lending rate has been halved while the rate of interest paid on savings accounts has fallen much more steeply. Meanwhile and counter-intuitively the exchange rate of the Guyana dollar to the United States dollar has fallen from $122.75 to $203.75.

Table 1

Source: Bank of Guyana publications

Some aggregate numbers

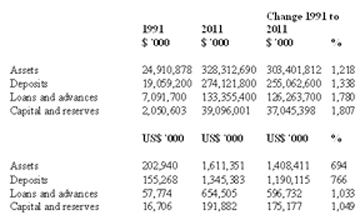

The banks have become bigger, much bigger. Measured in Guyana dollars, their assets have increased by 1,218%; deposits by an even larger 1,338%, loans and advances by 1,780%. The comparable US dollar percentages are 694%, 766% and 1,033%. As noted above and shown in Table 4, growth has translated to handsome profits.

Commercial Banks

Table 2

Source: Bank of Guyana publications

Market share

While concerns may be expressed about the conduct of the commercial banks in a wider sense, there is no doubt in my mind that there is intense competition for loans and advances to customers.

![]() There appears to be far too restrictive policy on making loans to non-resident companies which almost invariably have to bring money into the country on the mistaken ground of crowding out rather than borrowing from the local banking sector. At December 31, 2011 loans and advances by the commercial banks were less than 50% of their deposits which many consider are not growing as fast as they can because of interest rates that deter rather than encourage savings.

There appears to be far too restrictive policy on making loans to non-resident companies which almost invariably have to bring money into the country on the mistaken ground of crowding out rather than borrowing from the local banking sector. At December 31, 2011 loans and advances by the commercial banks were less than 50% of their deposits which many consider are not growing as fast as they can because of interest rates that deter rather than encourage savings.

The banks however face some countervailing challenges when it comes to the economy. Some of the main players in some of the fastest growing sectors such as gold, construction, the narco-sector (which has earned special mention), the still huge underground economy and the Chinese and Brazilians, seem more interested in shipping money out of Guyana rather than borrowing from the commercial banks.

As a result of the restrictive lending rules and the nature of key sectors of the economy, market share in the banking sector, and more especially in their hugely profitable lending operations, is vital to profitability. This is how the banks stood in (2011), the last date at which figures are available. These numbers are more than just instructive.

As a result of the restrictive lending rules and the nature of key sectors of the economy, market share in the banking sector, and more especially in their hugely profitable lending operations, is vital to profitability. This is how the banks stood in (2011), the last date at which figures are available. These numbers are more than just instructive.

One area of concern about the banks are the charges they impose on what might appear to be their miscellaneous services such as foreign exchange operations, letters of credit, returned cheques, copies of statements, etc. Interestingly, while in the case of NBIC/RBL, the percentage which such other income bears to its other income and net interest income has increased from 22% in 1991 to 27% in 2011, in the case of GBTI that percentage has fallen from 27% to 24%. Comparable percentages for the other banks are Citizens Bank 25%, Demerara Bank 28% and Bank of Baroda 33%.

Another interesting statistic is that in every bank, the salary and related costs are more than covered by other income alone, maybe strengthening the argument for more favourable interest rates, subject to the usual rules applying to risk levels.

The future

The picture for the banking sector looks rosy.

The sector will continue to be driven by technology and the banking licence – which has no carrying value on the balance sheet – will continue to be the most valuable asset, a licence to make money. While some entities will pursue the bricks and mortar strategy at least one other will see that as not the smartest approach to banking in an increasingly technologically driven environment.

Technology will play an even greater role in the sector as mobile money takes root and measures to strengthen controls and prevent increasingly clever and daring frauds continue.

But then the future is never certain. While money laundering will continue to play a significant role in the economy, with the non-bank cambios prominent, the commercial banks’ risk will not be helped by the tepid supervision of money laundering. This is likely to increase as the distributive trade continues its evolution.

There is no new legislation on the horizon and the principal regulator of the sector will continue to pursue conservative, non-interventionist policies.

Without some kind of revolutionary thinking and approaches neither the consumer nor the labour movement will exert any influence on the sector.