CARACAS (Reuters) – Venezuela’s vice president hit out at the country’s business leaders yesterday, saying they were seeking to destabilize the nation while cancer-stricken President Hugo Chavez fights to recover from surgery.

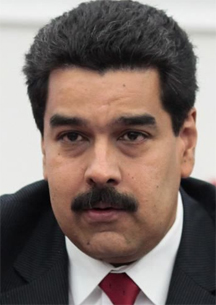

Chavez has not been seen in public nor heard from in five weeks since his latest operation in Cuba, and his heir apparent Nicolas Maduro has taken on an increasingly visible role as the face of the government.

Accused by the opposition of presiding over a troubled economy afflicted by 20 per cent inflation and shortages that the authorities blame on hoarders, Maduro rejects the charges as part of a malicious campaign against Chavez’s leftist project.

The main private sector chamber, Fedecamaras, complained last week about the “urgent need” to address growing economic imbalances that it said were caused by insecurity, instability and misguided policies. That provoked a stern response.

“It takes your breath away, the hate they have for the Venezuelan people,” Maduro said during a televised tour of a market selling state-subsidized food.

“Get lost, Fedecamaras! Here we have a revolutionary government that is going to continue pursuing hoarders, as well as the badness, intrigue and lies which you represent … there is a psychological war to demoralize and confuse our people.”

In Chavez’s absence, former bus driver-turned-foreign minister Maduro has increasingly swapped his business suits for the casual tracksuits favoured by his boss. But he has struggled to replicate the president’s powerful folksy charisma.

For his latest Chavez-like state TV appearance, he adopted something of a greengrocer’s manner at the open-air market in Carabobo state, inspecting pastries, holding aloft vegetables and remarking on the freshness of fish.

“Just in today … so tasty, we only have this quality for you!” Maduro told a crowd of shoppers, many of whom wore red Socialist Party T-shirts and chanted: “We are Chavez!”, “The people are with you!” and “(The opposition) won’t return!”

Major policy decisions appear to be on hold while Chavez, 58, battles to return after his fourth cancer operation in just 18 months. That includes the question of a devaluation of the bolivar currency that local economists say is long overdue.

A devaluation would increase state revenue from oil sales, but would also push up prices. In late 2011, Chavez’s government extended controls that regulate prices of products ranging from meat to deodorant, while fixing profit margins.

That kept a lid on prices during 2012 despite blow-out government spending on popular welfare programmes that helped Chavez win a new presidential term at an election in October, and helped Socialist Party candidates triumph in 20 of the country’s 23 states at a gubernatorial vote in December.

A devaluation would also slow capital flight, and would ensure merchants have dollars to import basic products such as wheat flour that have disappeared sporadically in recent weeks.

Barclays Capital, which expects a devaluation of about 40 per cent, said if the government planned to hold a new presidential election within three months, officials would probably postpone the adjustment in order to put off taking the political hit.