Benefits for Tax Contributions

Undoubtedly, the private sector has seen benefits for the tax contributions that it provides. One source of evidence is the special funding arrangements enjoyed by some members of the private sector in pursuit of their investment goals. The public-private partnership touted in the construction of the Berbice River Bridge is supporting evidence. Some undoubtedly benefited from the debt written off through the World Bank and Paris Club debt forgiveness programmes for Highly Indebted Poor Countries. The private sector has also enjoyed lower tax rates on business income starting in 2010 in addition to the special provisions in the tax laws for computing taxes on business income. Another indicator is the value of procurement contracts allocated to the private sector. From just two examples in 2011, in excess of $2 billion in contracts were awarded to a few members of the private sector.

Reallocation of Resources

While the income tax contribution of all businesses has grown by an average of 13 per cent per annum since 2002, the income of some businesses before tax has grown at phenomenal rates, in some years reaching 40 and 50 per cent speeds. It is no accident that the private sector has enjoyed this level of success because the administration allocated tax dollars to support a variety of activities in the private sector, including institutional and capacity building of companies within that part of the economy. The reallocation of resources was aimed at buttressing companies thought of as helpless that operated as monopolies and oligopolies in the domestic market. The reallocation of resources supported, inter alia, the participation of local companies in overseas trade fairs and domestic exhibitions. The expected outcome from this and similar courses of action was job creation by the private sector to make a significant impact on unemployment and to reduce poverty. Data on the number of jobs created by the private sector during the period of implementation of the Poverty Reduction Strategy are not readily available. Consequently, it is not possible to determine how effective the redistribution of income was in achieving the stated goals.

Environmental and health hazards

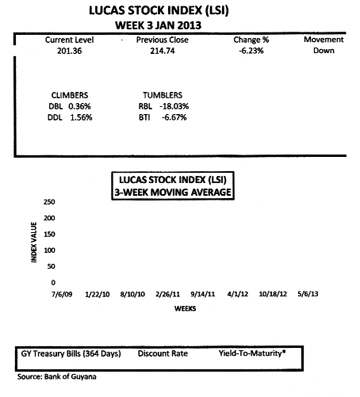

The Lucas Stock Index (LSI) declined by over 6.23 per cent in the third week of trading in 2013. Six stocks traded with four of them showing contrasting movements. Demerara Distillers Limited (DDL) and Demerara Bank Limited (DBL) recorded positive gains of 1.56 and 0.36 per cent respectively. However, the negative movement of 6.67 and 18.03 by Guyana Bank for Trade and Industry (BTI) and Republic Bank Limited (RBL) respectively overpowered the gains of DDL and DBL. Banks DIH (DIH) and Demerara Tobacco Company (DTC) gave no help to the index with their unchanged value from last week.

One could only imagine then that the business community feels that public expenditure is beneficial to it, and therefore, might see budget deficits as acceptable public policy. At the same time, individual taxpayers have had to endure some highly unacceptable outcomes like a filthy environment, inadequately developed infrastructure for new housing schemes, unsatisfactory electricity and water supply, and improperly maintained drainage systems. What is troubling is that the Poverty Reduction Strategy understood that these environmental and health hazards were constraints to economic advancement and the reduction of poverty. Yet, after several years of implementing the strategy, not only the poor, but almost all Guyanese live or dwell in insanitary environments. Almost every gutter or canal is loaded still with food boxes, plastic bottles, old cloth and other types of debris. Alleyways, apart from being overgrown with grass, are silted up to such heights that the slightest rainfall leaves them overflowing their sides, and helping to flood the yards of residents. Further, distinctions between commercial and residential areas have been eroded or have disappeared altogether.

Critical review

The allocation and redistribution initiatives of the administration are now subject to critical review. At least that is what should be taking place now that the administration has lost control of the legislature. Some evidence of that is occurring in the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) where budget agencies are being made to explain potential violations of the law. The political change also means that greater numbers of individuals have a new opportunity to have their concerns about public spending aired independently of the interests of the administration. It is therefore important that, for the 2013 budget, in addition to the private sector, the combined opposition should be a part of the discussions prior to finalising budget proposals.

The presence of the opposition with a voice of influence is also a new reality for the business community. That constituency now has to share its thinking about the economy not only with the administration, but also with the combined opposition to ensure that the latter is also supportive of its ideas. The opportunity for dialogue is healthy since it is a medium through which many thoughts about the future of the Guyana economy could be filtered. It also opens space for the implementation of initiatives that can have a broader and more favourable impact on the lives of Guyanese. Undoubtedly, concerns about equity and fairness could increase among the business community if the benefits that it has been enjoying are reduced as a result of a reorientation of priorities and tighter control on public sector spending.

Tax structure

There is another reason that the taxpaying public should have its representatives heard in the budget preparations, and in the management of the national economy. Changes to the tax structure in 2006 have seen the income tax diminish in relative importance to government revenue and give way to the consumption tax, more notably the value-added tax (VAT). This change became noticeable in 2007 when Guyana began using VAT in addition to income tax, among others, to raise revenues for public spending. While VAT was new, it simply replaced other consumption taxes that were in use. At the same time, the amount of goods and services subject to consumption increased significantly. By increasing the amount of goods and services that were subject to VAT, tax levels went up and so did government revenues. There is no evidence that the increased tax revenues translated into higher transfers to all the vulnerable segments of the population as would be expected of an administration that was ostensibly concerned about poverty reduction and the welfare of its citizens.

Regressive nature of VAT

The regressive nature of VAT raises issues of the likely loss of consumer welfare owing to the higher cost of acquiring VAT-laden goods by persons with relatively small incomes. The likely loss of consumer welfare is compounded by the reality that most domestic companies operate as monopolies, oligopolies or in highly concentrated markets. Domestic production for many household goods is probably below desired levels. That increases the risk of welfare loss for low-income persons since most likely they are priced out of the VAT-laden market by the inefficiencies of the production process. Consequently, the reduction in consumption which VAT is intended to achieve might be coming from that segment of the population which needs to maintain consumption levels to have a decent standard of living. No one knows for sure since there are no published studies as yet on the impact of the application of VAT on consumption, and where the incidence of the tax is falling. Such a study is required to ensure that low-income Guyanese who tend to spend all of their money are not bearing the greater burden of the tax.

Voices heard

With the opposition controlling part of the government, Guyanese of all persuasions have a chance to make an input into the decisions on spending by the administration. They also get to say how the funds are distributed even though the responsibility for spending the money rests with the administration. Even though they do not directly have the ears of the administration like the business community does, individual taxpayers could have their voices heard through the opposition. In that way, they get a chance at least to call some of the tunes like the representatives of the business community.