Introduction

As I was about to prepare Part II of my article on the 2011 Auditor General’s report on the Ministry of Finance, three media reports on the procurement of drugs and medical supplies for the Georgetown Hospital and the Ministry of Health caught my eye. The first relates to the Public Accounts Committee examination of the 2010 Auditor General’s report where the Permanent Secretary was grilled about purchases made, especially from a local organisation. The second report was about a call from one of the Opposition political parties for a full investigation into the matter. The third item relates to a senior Government functionary seeking to defend the Government’s action by asserting that although the procurement might be viewed as one of sole sourcing, the two agencies do carry out checks to ensure that the prices paid are realistic and competitive.

Today, we step aside for a while to provide an analysis of the Government’s procurement of drugs and medical supplies over the last ten years or so. Much of the information is gleaned from the reports of the Auditor General dating back to 2000. Except for 1992, earlier reports are not available at the Audit Office’s website.

Procurement arrangements prior to 2004

In view of the large volume of drugs and medical supplies needed for the Georgetown Public Hospital and the Ministry of Health as well as the size of the expenditure, it is necessary for some mechanism to be put in place in relation to their procurement to ensure fairness and equity among suppliers and to achieve the best value for money. While up to 2003, the Tender Board Regulations were being used, such regulations did not have the force of the Law, compared with what currently prevails with the passing of the Procurement Act. It was mainly for this reason that the Cabinet had a major say in terms of how and from whom drugs and medical supplies were to be procured. In this context, the Cabinet decision of 15 May 1997 authorising the purchase of drugs and medical supplies from specialized overseas agencies based on a system of pre-qualification, is relevant. That decision was updated in November 2003.

With the passing of the Procurement Act and the establishment of the National Procurement and Tender Administration Board (NPTAB), the Cabinet’s authority should have ceased. The only involvement of the Cabinet under the Act is the offer of “no objection” in relation to the award of contracts in excess of $15 million. The Cabinet’s decision on the procurement of drugs and medical supplies from 2004 to the present time can therefore be viewed not only a usurpation of the authority of the NPTAB but also a violation of the Procurement Act 2003.

With the passing of the Procurement Act and the establishment of the National Procurement and Tender Administration Board (NPTAB), the Cabinet’s authority should have ceased. The only involvement of the Cabinet under the Act is the offer of “no objection” in relation to the award of contracts in excess of $15 million. The Cabinet’s decision on the procurement of drugs and medical supplies from 2004 to the present time can therefore be viewed not only a usurpation of the authority of the NPTAB but also a violation of the Procurement Act 2003.

Sole sourcing and the Public Procurement Act 2003

Section 28 of the Procurement Act states that where goods, services or works are only available from a particular supplier or contractor by virtue of their highly complex or specialized nature, or where the supplier or contractor has exclusive rights to these goods, services or works, procurement may be undertaken using the sole source method. This is assuming that no reasonable alternative or substitute exists. Additional supplies may be procured from this source because of the need to maintain standardization and taking into account the effectiveness of the original procurement. In such circumstances, advertisement and competitive bidding will not yield a different result, as there will be only one bidder. An example that comes readily to mind is the procurement of specialized defence and military equipment.

If we were to apply the above criteria, it is clear that drugs and medical supplies do not qualify for procurement via the sole source method. A system of advertisement, pre-qualification and competitive bidding from pre-qualified suppliers would have been more appropriate, as was done prior to 2005. Any procurement of drugs and medical supplies using the sole source method, although approved by the Cabinet, apart from violating the Procurement Act, will lack the requisite degree of transparency and accountability that is associated with the operations of government. At least one local supplier has publicly complained about unfair treatment arising out of the current arrangements.

In the private sector, procurement is sometimes carried out without advertisement and competitive bidding and there are usually in-house arrangements for comparing prices before proceeding with the purchase. However, private sector companies exist to make profits, and there are numerous incentives for company officials to ensure that profits are maximised. Managers are also given a significant amount of autonomy and flexibility to function in the furtherance of the company’s stated objectives.

Governments, on the other hand, do not exist to make profits but rather to render an economic, efficient and effective public service, using taxpayers’ money. It follows that public accountability has to be far more rigorous and requires the highest degree of transparency and accountability. This is why specific legislation and constitutional safeguards detailing the procedures to be followed are so vitally necessary to ensure that taxpayers’ funds are used wisely. There is no parallel in the private sector, as each company has flexibility to determine what is in its best interest, bearing in mind that if shareholders are dissatisfied with the company’s performance, there could very well be a change in the management structure.

Analysis of the purchase of drugs and medical supplies:

The 2003 Auditor General’s report referred to the purchase of drugs and medical supplies for the Georgetown Hospital and the Ministry of Health from overseas suppliers through selective tendering as approved by Cabinet decision of May 1997. Given that six years would have elapsed since the Cabinet made its decision, the report recommended that every three years there should be advertisement internationally for the pre-qualification of suppliers.

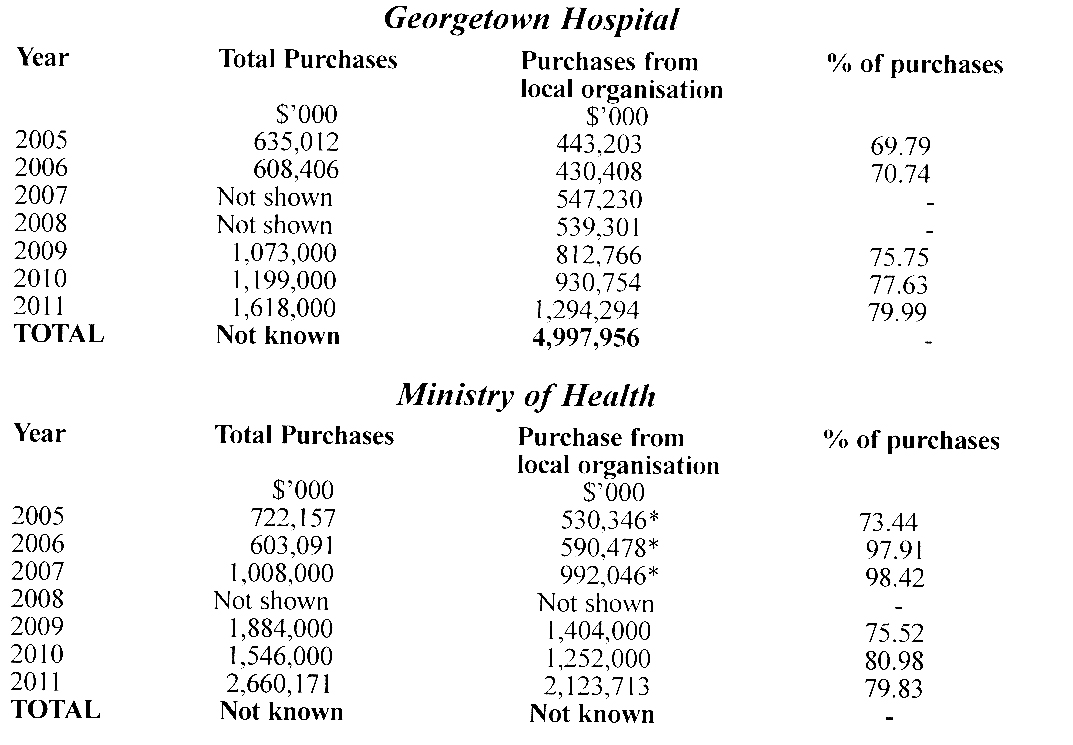

Since 2005, however, a local organisation has been the main supplier of drugs and medical supplies to the Georgetown Hospital and the Ministry of Health with approximately 75 per cent of their requirement, based on a new Cabinet decision of November 2003, and without any form of competitive bidding. During the period 2005 to 2011, these two agencies procured an estimated $16 billion worth of drugs and medical supplies. Of this amount, approximately $13 billion or 81 per cent was supplied by the local organisation, as shown in the following two tables.

The analysis below is somewhat incomplete because some of the information is not readily available in the Auditor General’s reports, though there was enough information to extrapolate. In addition, the fire, which destroyed the building housing the Ministry of Health on 17 July 2009, also destroyed essential accounting records, thereby placing a restriction on the work of the auditors.

In relation to the amounts shown with asterisks, although the organization was not specifically stated in the Auditor General’s reports for 2005, 2006 and 2007, the reports did indicate that these were purchases made locally in excess of $600,000 without any form of tendering and therefore did not conform to the requirements of the Procurement Act. Clearly, the Auditor General was referring to the local organization, hence the inclusion in the above tables.

The 2005 and 2006 reports indicated that the Georgetown Hospital did not have adequate supporting documents to enable the verification of the receipt of drugs and medical supplies. A similar observation was made in respect of 2007 in relation to the Ministry of Health. There was also evidence of rolling over arrangements from one year to the next in the supply of drugs and medical supplies, a practice that not only violates the Fiscal Management and Accountability Act but also renders the verification of the receipt of the items difficult.

Conclusion

The procurement of drugs and medical supplies for the Georgetown Hospital and the Ministry of Health remains a source of concern for Parliamentarians and the public at large. The sole source method of acquiring these items is not in keeping with the requirements of the Procurement Act. This practice has also resulted in dissatisfaction among local suppliers since without competitive bidding there is a lack of an even playing field among local suppliers. In addition, record keeping and monitoring of the purchases by the Georgetown Hospital and the Ministry of Health need to be significantly improved to ensure proper accountability and good value for money.

Finally, the Cabinet should cease being involved in deciding from whom drugs and medical supplies should be acquired, and allow the NTPAB to do its work in accordance with the Procurement Act. Meanwhile, the Public Accounts Committee should take urgent measures to establish the Public Procurement Commission.