Dear Editor,

It was interesting to read of the complaint in the press recently about the confusion surrounding the administration of the Associate Degree programme conducted jointly by the CPCE and UG.

It was at the same time puzzling to learn that the first programme was actually completed in 2012, when a team of consultants had only completed the reconstruction of the respective roles and responsibilities of lecturers involved and related support staff earlier the same year.

Hitherto only those who completed the two-year CPCE programme have been certified by the Teaching Service Commission as graduate teachers; while a UG student in English, Spanish, Geography, Maths having successfully completed any relevant programme of study is appointed a non-graduate teacher, on a lower salary scale.

It is not quite clear what level of pay will be attributed to the teacher with an Associate Degree. Many teachers are in fact unaware of the salary structure which obtains in their profession. One suspects that it would be equally incomprehensible to the more recent administrators, particularly those sufficiently imaginative to compare the TSC with the compensation structure of equally qualified counterparts in the Ministry of Education. (In the meantime that a graduate is not a ‘graduate’ makes for an interesting conundrum.)

The only explanation for the respective groups of educators/educationists appearing not to be uncomfortable with the current arrangements must be that neither has paid attention to the (in)equitability in the values of the other’s jobs/positions. It is very possible also that the educators have, by some stratagem, been constricted from insisting on exploring relative values of jobs in these two components of the education sector.

The Teaching Service Commission has been administering a structure of twenty salary grades for some time, and then a few years ago it inexplicably froze the top (TS 20) into a fixed salary. The result is that the principals of CPCE, GTI, NATI, LTI have been singled out for working for a fixed salary for the rest of their careers, regardless of performance achievements. There is no comparable arrangement perceivable in the public sector as portrayed by the national budget.

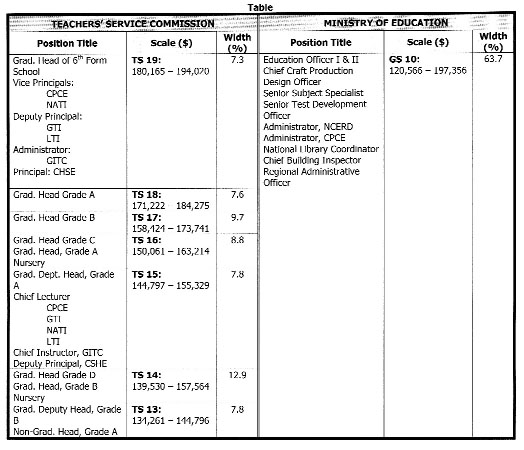

Meanwhile Grade TS 19 consisting of deputies to the above positions, as well as the principal, Carnegie School of Home Economics (CSHE); administrator, GITC; graduate head, 6th form school – ranges from $180,865 – $194,020 – a bandwidth of 7.3%. It provides serious pause for reflection, alongside the volunteered minimum annual increase of 5% to the public service.

For the record the bandwidths for grades TS 18, 17, 16 and 15, are respectively, 7.6%, 9.7%, 8.8% and 7.3%. All these relate to graduate heads of grades A, B and C schools.

The point is that these functionaries are required to meet the most stringent performance standards not only in the classroom, but also in management; delivery of targeted results; in relations with parents, the Ministry of Education, and the community at large. This is in addition to satisfying the requisite professional qualifications. One has to search diligently to find explicit similar competency comparabilities in the rest of the public service – even in health.

What may be considered ludicrous is that of the 14 scales in the public service, GS10: $120,566 – $197,356, virtually covers the range of values contained in TS Grades TS13 – TS19 plus the fixed salary (TS20).

The minimum of TS13 is $134,261 and the maximum of TS19 to $194,020 with the fixed at $204,126.

The following table should suffice as a sample of the pervasive differentiation, if not discrimination obtaining.

The following table should suffice as a sample of the pervasive differentiation, if not discrimination obtaining.

(Adjustments made since 2012 Budget should not substantially affect the relativities).

The whole pattern of differentiation must appeal to conscience and consciousness. The bandwidth of GS10 is 63.7%. Over the whole of the respective structures the average bandwidth in the TSC is 8.8% as compared to 74.7% in the public service. Surely on review there is a case for a more objective evaluation of job values across this Sector, which perforce will overspill into the rest of the Public Sector.

While the under-informed politicians chew on this morsel of food for thought, the least that can be done is to insist on an urgent programme of compensation adjustments within the education system, to stop not only the haemorrhage caused by the migration of teachers; but at the same time reduce proportionately the production of the under-educated from our school system.

It is against this background that one hopes that private sector employers, individually and severally, must consider reordering their investment priorities between education and sports, particularly in the latter case where several of the programmes/tournaments would not yield any national benefits, since they are organised only to promote consumption of respective products.

Our tertiary education system deserves, indeed demands, more substantive support.

Yours faithfully,

E B John