In this path (of disinterested action) there is no loss of effort, nor is there fear of contrary result, even a little practice of this discipline saves one from a terrible fear of birth and death.

Bhagavata Gita

Two weeks ago, we examined the 2011 Auditor General’s report on current expenditure of the Ministry of Finance. We found that expenditure on contracted employees accounted for almost 75 per cent of employment costs. The solution to the problem arising out of the disparity in wages and salaries paid, and to ensure transparency in the recruitment process, is a unified and professionalized Public Service with standardized pay and grades, fully administered by the duly recognized constitutional agency, the Public Service Commission. We also touched on the Lotto funds and the operations of NICIL, and we noted that the Auditor General stayed clear of any adverse comments relating to these two matters.

In my column of 24 September 2012, I did an analysis of the operations of NICIL from the point of view of the Companies Act 1991 and the Public Corporations Act of 1988. I had stated that NICIL is not a public corporation as there was no evidence that an order was issued under the latter Act deeming it as such. This was after strenuous efforts to obtain information from various sources, including NICL’s website and the Parliamentary Library.

A few days ago, I visited a professional colleague who also has a strong interest in the matter. He gave me a photocopy of a notification dated 18 July 2000 in which Section 5 of the Public Corporations Act, dealing with the vesting of movable and immovable property of the State, was deemed to apply to NICIL. Notwithstanding this, NICIL has not been deemed a public corporation in the context of section 6(2) of the said Act. Interestingly, the annual reports and the audited accounts of NICIL to 2010 as well as the consolidated accounts to the year 2005, did not include this vital piece of information so necessary for a proper understanding of NICIL’s operations. Because of this latest information, I propose to revisit the above-mentioned analysis in my next column.

A few days ago, I visited a professional colleague who also has a strong interest in the matter. He gave me a photocopy of a notification dated 18 July 2000 in which Section 5 of the Public Corporations Act, dealing with the vesting of movable and immovable property of the State, was deemed to apply to NICIL. Notwithstanding this, NICIL has not been deemed a public corporation in the context of section 6(2) of the said Act. Interestingly, the annual reports and the audited accounts of NICIL to 2010 as well as the consolidated accounts to the year 2005, did not include this vital piece of information so necessary for a proper understanding of NICIL’s operations. Because of this latest information, I propose to revisit the above-mentioned analysis in my next column.

I was also taken aback by the statement of NICIL’s Executive Director in relation to the ownership of NICIL. While a company is separate and distinct from its owners, it is the shareholders who are the real owners. The Executive Director went on to state that the Government is only a shareholder. This begs the question: Who are the other shareholders? The information contained in NICIL’s website as well as in the notification referred to above clearly indicates that the company is wholly owned by the Government! Section 344 of the Companies Act defines a Government company as “any company in which not less than fifty-one per cent of the paid up share capital is held by the Government and includes a company which is a subsidiary of a Government company”. This means that Atlantic Hotels Inc., as a subsidiary of NICIL, is also a Government company.

It is important to distinguish between limited liability companies whose shares are publicly traded, and those that are not. The former are described as public companies, for example, Banks DIH Ltd., while the latter are considered private companies, for example, Toolsie Persaud Ltd. Although NICIL is a Government company, it was incorporated as a private limited liability company, meaning that there are restrictions in terms of shareholdings. The word “private” in this context is a kind of misnomer because it connotes that the Government has nothing to do with the company whose affairs are a private matter. From now on, we should describe NICIL as a Government company and cease considering it a private limited liability company. To do otherwise is to mislead the public.

We now conclude our review of the Auditor General’s report on the Ministry of Finance by looking at capital expenditure as well as both capital and current revenue. As mentioned previously, the Auditor General’s report did not include any commentary in relation to these areas although vast sums of money were involved.

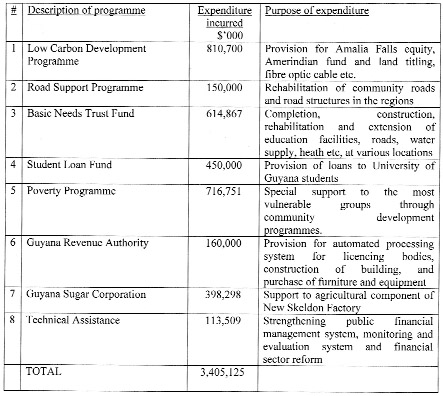

The total amount expended on the Ministry’s capital programmes amounted to $3.698 billion, compared with an approved allocation of $17.431 billion, giving a shortfall of $13.733 billion or 76 per cent. There were 19 programmes of capital expenditure, of which the following is a list of the main programmes:

The amount budgeted for the Low Carbon Development Programme (LCDP) was $14.350 billion. It is public knowledge that the anticipated flow of funds from the Guyana REDD Investment Fund did not materialize, hence the shortfall in expenditure. A detailed explanation, including the economic impact, should have been given in the budget outcome and reconciliation report, as required by the FMA Act 2003 when there are significant variances between budgeted and actual outcomes. The fact that this was not done should have prompted the Auditor General to seek out the explanation and have it included in his report. An interesting aspect of the proposed expenditure on the LCDP is that the entire financing was shown as Central Government financing, and that there was no direct foreign expenditure.

In relation to the Basic Needs Trust Fund (BNTF), financing is from the Caribbean Development Bank (CDB), with a small contribution from the Government. This programme is subject to separate financial reporting and audit. The Auditor General’s report on the audit of foreign funded projects indicated that one audit was completed in respect of funding from the CDB. It is not clear whether this refers to the BNTF since the programme for the GRA also involves joint financing from the Government and the CDB. A similar observation is made in relation to the Technical Assistance Programme jointly funded by the Government and the Inter-American Development Bank where the Auditor General stated that five such audits were completed.

The Student Loan Fund is subject to separate financial reporting and audit. Although not specifically mentioned in the Auditor General’s report, it is understood that the last set of audited audits of the Fund is in respect of 2010. The Poverty Programme is exclusively financed by the Government and therefore there is no requirement for separate financial reporting and audit.

As regards GUYSUCO, as a public corporation, we know that it is subject to separate financial reporting. The Auditor General’s report indicated that 12 audits of public enterprises were finalized under the contracting out arrangement but there was no specific mention of GUYSUCO. A check of GUYSUCO’s website indicates that it is fairly up-to-date in terms of its audited financial statements.

The amount budgeted to be collected was $20.397 billion while actual collections totaled $7.778 billion, giving a shortfall of $12.619 billion. This was due mainly to the anticipated flow of funds from the Guyana REDD Investment Fund, which, as mentioned above, did not materialise. Again, we can note that there was no detailed explanation, including the economic impact, in relation to this significant shortfall.

The Government has treated the Guyana REDD Investment Fund as revenue earned and therefore belonging to Guyana. International accounting standards prescribe detailed rules regarding revenue recognition. In particular, the standards define revenue as “the gross inflow of economic benefits or service potential during the reporting period when those inflows result in an increase in net assets/equity other than increases relating to contributions from the owners”. Revenue is also recognized when it is probable that future economic benefits will flow to the entity and that these benefits can be measured reliably. It is not clear to what extent these rules were applied in deciding on the accounting treatment of the Guyana REDD Investment Fund.

Some critics would argue that the criteria for revenue recognition may not have been met, and that it would have been more appropriate for the inflows from the Guyana REDD Investment Fund to be treated as a grant. Unfortunately, Guyana has not yet adopted any of these accounting standards. It continues to operate with the outdated and outmoded cash accounting system inherited since Colonial times although the FMA Act 2003 mandates the Minister to promulgate accounting standards for use by the Government.

Capital revenue

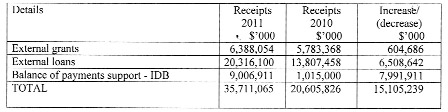

The budgeted amount for capital revenue amounted to $39.710 billion while actual receipts totaled $36.756 billion, giving a shortfall of $2.954 billion. The following table shows the main areas of actual receipts.

The increase in external grants results mainly from an increase in contributions from the European Union of $2.552 billion. In terms of the external loans, the increase was due mainly to additional loans amounting to $1.417 billion from China while other project loans increased from $345.5 million to $7.145 billion. However, details of the latter were not shown in the accounts. The balance of payments support from the IDB has also increased nine-fold.