This brief feature on the Chinese which has been edited, was first published by the Stabroek News on January 9, 1988.

The presence of new Chinese immigrants among us is often remarked upon. They are, however, merely the latest wave in a continuing story of immigration to this country. January 12, 2013, marked the 160th anniversary of the arrival of the first Chinese in Guyana.

Immigrants

The first 647 Chinese were brought into the colony of British Guiana in three ships during 1853. The first boat to dock on January 12, 1853 was the Glentanner, carrying 262 passengers from Amoy. These were distributed amongst the plantations of Windsor Forest (West Coast Demerara), Pouderoyen (West Bank Demerara) and La Jalousie (West Coast Demerara), while one lone soul was sent to Union in Essequibo.

Shortly afterwards, a Bookers boat, the Lord Elgin, arrived on January 17. She only disembarked 85 passengers, however, since 44.8 per cent of her original complement had died on the voyage. The high mortality was attributed to the fact that after the vessel had sprung a leak, some rice stowed below decks had become saturated and had begun to ferment.

The badly ventilated ship was consequently soon filled with sulphurated hydrogen. The survivors from this ordeal were sent to Blankenburg on the West Coast of Demerara. A third boat arriving in March of 1853 disembarked 300 Chinese.

These first immigrants were exclusively male; women were not brought in until 1860, when the Whirlwind and Dora arrived from Hong Kong carrying 61 and 138 female passengers respectively. According to Cecil Clementi, who wrote a history of the Chinese in Guyana in the early 20th century, the percentage of women in the total Chinese immigration was only 14.2 per cent. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that the vast majority of Chinese men had to seek partners outside their own ethnic grouping.

Unlike other groups, repatriation to their original homeland was particularly difficult for the Chinese. Apart from two exceptions which occurred in 1870 and 1871 when 29 Chinese prevailed upon the governor to pay their passages to Calcutta, after which they were to find their own way to China, home-bound Chinese had to pay their own fares. Nevertheless, this did not deter would-be emigrants from leaving the country. They could not return home easily, but they went in some numbers to Suriname, Trinidad, Saint Lucia and even Jamaica.

According to Clementi’s calculations, the total number of Chinese who entered the country between 1853 and 1913 stood at 15,720. In 1911 there were only 2,622 of them resident here, which meant, said Clementi, that almost 9 out of 10 men had left again, and approximately half the women.

Hopetown

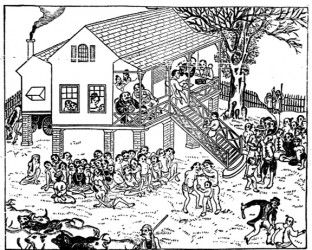

Like other 19th century immigrants, Chinese were imported to work on the plantations. When their period of indenture had been completed, some did consent to re-indenture themselves but as mentioned above, many left the country altogether. There was one group, however, which with the assistance of Governor Hincks set up a settlement in the Kamuni Creek, approximately 30 miles up the Demerara River. The leader of the settlement was O Tye Kim, who had originally come from the Straits Settlements (Singapore and other territories which are nowadays part of Malaysia). Educated by the London Missionary Society in Singapore, he had worked as a surveyor in the latter colony.

It was as a missionary, however, that he first arrived in this country, and he was soon to acquire considerable influence among the Chinese immigrants. Kim played a critical role in the establishment of Hopetown village in 1865, and after some initial difficulties it was deemed a success story within the space of a year.

The foundation of its economy was charcoal burning, which the Chinese did more efficiently than the local people. The latter burnt in pits, while the Hopetown residents built special clay furnaces which could handle larger quantities of wood and turned out a better quality product. The charcoal was sold at an outlet in Georgetown, and because it was cheaper than that produced by anyone else, it soon came to monopolise the market.

It was through money made in Hopetown that some Chinese were able to break into the retail trade despite Portuguese domination in that area. The traditional association of the Chinese with commerce in this country, therefore, began with the Hopetown settlers.

Unfortunately the Hopetown success story was to fade out for a variety of reasons, one of which was the departure of O Tye Kim. After being officially appointed Missionary to the Chinese by the Bishop of Guiana in 1866, an indiscretion the following year caused O Tye Kim to flee, and the settlement was left to manage as best it might without him. In fact, it went into a steady decline from which it never recovered, as a consequence of which no further experiments along these lines were ever attempted.