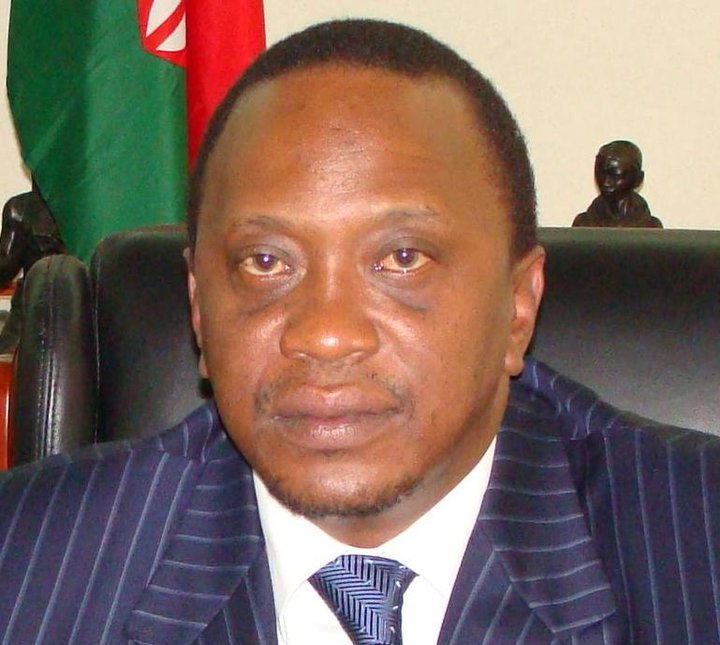

NAIROBI, (Reuters) – Uhuru Kenyatta’s victory in Kenya’s presidential vote presents Western states with the challenge of keeping an elected leader charged with crimes against humanity at arms length while preserving valuable security and business ties.

Much is at stake in the relationship between East Africa’s biggest economy and its main Western backers and donors.

A diplomatic fumble in dealing with Kenyatta could damage ties with a nation that has helped quell militant Islamists in the region and push a traditionally pro-Western state closer to China and other emerging powers hungry for openings in Africa.

Kenyatta was declared president-elect at the weekend, after securing just enough votes to win in the first round, handing him the post his father held after Kenya’s 1963 independence, although his main rival Raila Odinga has challenged the outcome.

“It is extremely problematic for the West partly because several Western officials inserted themselves into the Kenyan election campaign and made pretty clear they thought Kenyans should not vote for Kenyatta,” said Africa Confidential editor Patrick Smith. “That triggered … the opposite response.”

The 51-year-old may owe some of his votes to Kenyans riled by what they saw as “meddling” when Washington, London and others cautioned before the election about the consequences of a win by Kenyatta, the U.S.-educated deputy prime minister.

The West’s day-to-day diplomacy will now be a more awkward affair, though it could in part be shaped by pressure from energy companies and other foreign firms determined not to miss opportunities in a region that may be on the verge of a hydrocarbons-fuelled boom.

However, relations will largely hinge on whether Kenyatta and his running mate, deputy president-elect William Ruto, who is also indicted, live up to their pledge to cooperate with the International Criminal Court in The Hague to clear their names.

Western diplomats have been coy in outlining what keeping diplomatic dealings down to “essential contacts” means in practice, perhaps allowing them as much room for interpretation as possible as they assess how Kenyatta handles the case that alleges he had a role in the post-2007 election bloodshed.

DIPLOMATIC DILEMMA

Offering some encouragement to Western capitals, Kenyatta pledged in a victory speech to cooperate with “international institutions” although he said the world should also respect Kenya’s “democratic will” – drawing applause in the hall.

Diplomats have not disguised the dilemma. When British High Commissioner Christian Turner spoke last month about Kenyatta and Ruto’s bid for the presidency, he made clear the challenge facing diplomats in Nairobi. Some Kenyans saw his comments as interference in the race

“It is difficult for us that I am not able to meet and talk to such important politicians in the affairs of Kenya,” he said in the interview with Kenyan television, refusing to be drawn on what exactly he would do if Kenyatta was elected saying “I will cross that bridge when I get to it.”

In private, diplomats say precisely how they will respond will be determined as it becomes clear whether Kenyatta and Ruto are meeting ICC obligations in office.

Kenyatta faces his own high-wire act as he seeks to run a country of 40 million people while cooperating with a trial in The Hague to start in July. How much time he needs to spend there or whether he can absent himself from hearings is still unclear.

His rival, Odinga, quipped during campaigning that Kenyatta would have to govern by Skype from the Netherlands.

But no one expects Kenya go the way of Sudan, the only other country where a sitting president faces ICC charges. President Omar al-Bashir has refused to recognise the court, further isolating Khartoum from the West. Kenya is “light years away from that” said Smith and diplomats want it to stay that way.

“We feel if you’re under suspicion of a crime that you step aside and clear your name first,” said one Western diplomat, asking not to be named because of the subject’s sensitivity.

But he added: “It won’t be a headache as long as (Kenyatta) cooperates with the ICC.”

Indicating the careful calibration, the United States and others in the West congratulated Kenyans on the vote but not Kenyatta by name, using wording that was similar enough to hint at coordination.

SECURITY WORRIES AND ‘REALPOLITIK’

The United States, Britain and the European Union, all big donors to Kenya, have good reason not to want to see a Kenyatta presidency undo long standing relations.

Western firms are well-entrenched in Kenya’s economy which has steadily recovered from the hammering after the violence that followed the 2007 election. Diageo and Vodafone are among the big players.

Kenya is a vital trade link for the rest of east Africa, where energy explorers include Britain’s Tullow, Canada’s Simba Energy and New York-listed Anadarko Petroleum. Regardless of Kenya’s own reserves, its ports will play an export role for finds elsewhere.

Aly-Khan Satchu, who was a former interest rate trader in London before moving to Kenya as analyst and trader, said a misstep by the West risked letting Kenya “run into the eager embrace of China and India”.

“U.S., UK and EU foreign policy has been framed ideologically of late and ‘realpolitik’, security and business interests might seek to exert more influence over the policy makers and their responses over the coming weeks,” Satchu said.

Security worries loom large. Kenyan troops have been at the vanguard of an African peacekeeping mission, backed by the West, to quash Islamist militants in Somalia. That intervention may have finally set Somalia on a bumpy road to recovery.

Washington donates around $900 million a year to Kenya, much of it for AIDS victims, but part goes to security cooperation.

While Western diplomats determine their actions, Kenyatta will have to make his own careful calculations. His team lambasted Western “interference” in the campaign, but Kenyatta will not want to a jeopardise long-standing and lucrative ties.

Much may be determined by the way the ICC case proceeds.

His lawyers and independent observers say the case against him is looking ragged. Citing the unreliability of a key witness for the prosecution, Kenyatta’s defence team have asked for the file to be returned to the pre-trial chamber, calling for it to be thrown out before the trial’s start date of July.

Independent observers also cite shortcomings. “It’s a live option that the case gets dismissed,” said Bill Schabas, professor of international law at Middlesex University in London.