The following is a minimally edited address to the 2The surge in crime in Guyana started at the dawn of the new millennium– coinciding with the implantation of the transnational trade in illicit narcotics. This trade perversely mimicked licit international commerce in its use of international air and maritime transport, its pursuit of new markets, its distribution network and its access to the invisible flow of convertible currency.

Criminal cartels, unlike law-abiding corporations, however, were willing to adopt violent means to protect their profits and their territory and to destroy their competitors. The potential for conflict between cartels, states, law-enforcement agencies and citizens is extraordinary.

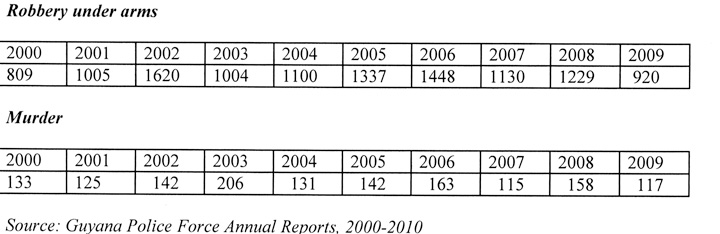

The evidence of the rising rate of criminal violence in Guyana – derived from the Police Force’s own daily bulletins – indicates an increase in theincidence of armed robberies and murders.Reports show that there were 1,701 murders and 11,602 robberies under arms in the decade from 1st January 2000 to 31st December 2009. There are, on average, about three armed robberies every day and two murders every week:

The Guyana Police Force reported, further, that robberies under arms increased by 21 per cent to 1, 065 and murders increased by 5 per cent to 137 in 2012, compared with 2011. The murder rate for 2012 was only very slightly lower than the rate for 2002 when the Troubles were raging.

The Guyana Police Force reported, further, that robberies under arms increased by 21 per cent to 1, 065 and murders increased by 5 per cent to 137 in 2012, compared with 2011. The murder rate for 2012 was only very slightly lower than the rate for 2002 when the Troubles were raging.

Maritime piracy along the waters off the coastland and banditry in the hinterland have been other sources of criminal violence which affect economic activity. Occasional discoveries of abandoned corpses or the gutted cadavers of artisanal fishermen at various locations along the coast and in the estuaries of the great rivers have dampened mining and fishing activities and remain reminders of the impact of crime on the economy.

The Police Force as it is presently constituted is incapable of effectively enforcing the law in the huge hinterland west of the Essequibo River. There, bandits attack, rob and kill miners, ambush travellers and often settle disputes with gunfire. The hinterland is an economic zone not only for logging and mining but also for gold and diamond smuggling, fuel smuggling, gun-running, narco-trafficking and assorted contraband activities.

A former Minister of Tourism, Industry and Commerce once lamented the damaging effect of crime on the tourism industry. He said, “We can have all the resorts; we can have a good product; we can have all the marketing strategies in place; we can have the airlines bringing down their air fares but, if the crime situation in Guyana is escalated, then it affects tourism.”

The post-2000 wave of industrial-scale narco-trafficking was accompanied by gun-running and money-laundering. Rogue policemen, ‘phantom’ death squads and gangs of bandits all contributed to the high toll of murders during the ‘Troubles.’

The general belief is that many execution-type murders were associated with the narco-trafficking and money-laundering enterprises. The continuation of executions suggest that, as long as narco-trafficking continues, contests and disputes will be settled by violent means.

The trade in illegal weapons, imported to protect the trade in illegal narcotics, has enabled criminals of any description to possess firearms. The result has been that drivers of delivery trucks; grocery stores; internet cafés; payroll clerks; private households; overseas-based visitors; service stations; vendors and even small-scale business persons have not been immune to the epidemic of armed robbery.

The Administration should be well aware of just how bad this country’s public security and human safety record is and what needs to be done about it. There is a copious stock of reports and recommendations. The security sector reform archives can be dated at least from 2000 with the Guyana Police Force Strategic Plan prepared by the UK-based Symonds Group. It continues up to the present Guyana Police Force Strategic Plan prepared by the UK-based Capita-Symonds Group.

Guyana has witnessed, in the intervening years, the promulgation of a National Drug Strategy Master Plan; a Presidential Menu of Measures; a series of reports of the National Security Strategy Organizing Committee, the Border and National Security Committee, the National Consultation on Crime, the UK Defence Advisory Team, the Disciplined Forces Commission and the Scottish Police College and attempts to introduce a Crime Stoppers’ Programme. We have seen, also, the signing of the President Jagdeo-Baroness Amos agreement on the ‘Statement of Principles’ for security cooperation; the Guyana-Britain Interim Memorandum of Understanding for a Security Sector Reform Action Plan and the IDB-funded Citizen Security Programme. We have witnessed the enactment of a raft of security-related laws and the establishment of several committees – including the National Commission on Law and Order, the Task Force on Fuel Smuggling and Contraband, the Task Force on Narcotic and Illicit Weapons and the Task Force on Trafficking in Persons. Many of these laws, plans and reports, recommendations and remedies have never been fully implemented.

Several factors have contributed to the sharp rise in crime. These include the venality of the Police Force, the vitality of the drug cartels and the lack of political will on the part of the administration. These factors contributed to making the last decade a murderous episode for citizens in this country. The advice of Heraldo Muñoz, Assistant Secretary General of the United Nations who wrote on crime and violence in the Caribbean, “The resulting alarm has often led to short-sighted, manodura (iron fist) policies which have proven ineffective and, at times, detrimental to the rule of law”should not be ignored.

Estimates, which cannot be confirmed, indicate that the corporate community might have lost over two billion dollars owing to robberies during the Troubles between 2000 and 2010. Concerns persist in various business associations, understandably, about the high cost of crime.

Robberies under arms, execution-murders and other forms of criminal violence instill fear in the victims. Fear leads to higher costs of doing businessowing to the need to employ additional forms of security and to divert investment away from business expansion to security.

Production can be lost as a result of reduced hours of operation. Output can also be reduced as a result of the temporary or permanent removal of individuals from the labour force. Criminal violence can cause a permanent closure of businesses or relocation to more secure destinations, eroding the development of human and social capital, limiting this country’s potential for growth and motivating managers to migrate. The loss of confidence in the law-enforcement agencies can force businessmen to resort to their own remedies by making their firms less vulnerable to crime. These can include establishing their own, or contracting the services of, commercial security forces and installing alarm systems, electronic surveillance systems, fences, grills and taking other protective measures aimed at protecting their enterprises.

This country will be secure only when the administration begins to transform the security sector in a serious way. The private sector cannot prosper in a state of perpetual crisis.

David Granger is Leader of the Opposition in the National Assembly