Sudden willingness

Without getting into the merits or demerits of the case, it is reasonable to say that the 2013 Budget has an unusual orientation towards the individual taxpayer. This article does not seek to address the political motives behind the unusually favourable treatment of the Guyanese taxpayer by the administration. Instead, it intends to examine how the administration might have used the tax structure in this budget to improve the position of the wealthy Guyanese far beyond their current pleasures under the guise of seeking to help the poor and aged. One cannot help wondering about the sudden willingness of an administration that has shown scant regard for the concerns of the not-so-privileged Guyanese seeming to be overly concerned with the plight of this segment of the population. The shift in sympathies is so extensive that the administration found it possible to apply in one sweep multiple direct tax measures in favour of taxpayers.

Direct taxes

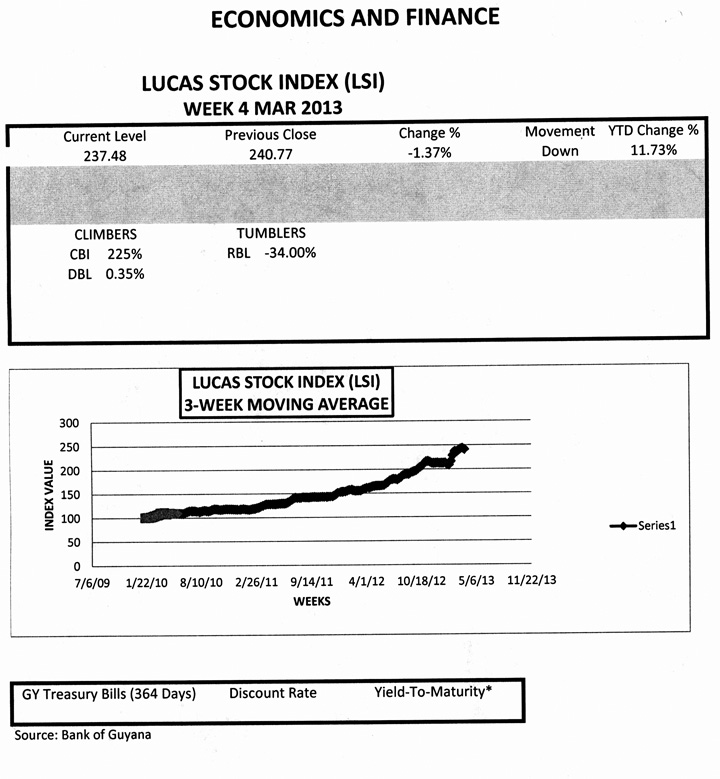

The Lucas Stock Index (LSI) declined by 1.37 per cent in the fourth week of trading in March 2013. The stocks of five companies traded with varying results. Citizens Bank (CBI) came alive with a 325 increase in value. Demerara Bank Limited (DBL) rose slightly by 0.35 per cent. Like the previous week, the stock of Republic Bank Limited (RBL) recorded a loss, declining 34 per cent in value. Banks DIH (DIH) and Demerara Tobacco Company (DTC), which also traded, recorded no change.

Direct taxes are the part of the tax structure that does not depend on action by taxpayers for a liability to be imposed on their income. It merely requires them to be in possession of income and or property to be subject to assessment. However, tax rules determine the level of income that become subject to taxation. This is different from the indirect taxes such as the value-added tax and import duties, which are triggered when Guyanese spend money on items of consumption or when they import items from abroad. In Guyana, direct taxes are made up of the income tax, the payroll tax, and the estate and property tax. All three categories of taxes are imposed on both individuals and businesses, albeit at different rates. This article is concerned with the implications of the income tax and the property tax on Guyanese taxpayers.

Concessions

For the first time in a long time, the two direct taxes have featured simultaneously in the national budget of Guyana. It has usually been the income tax that has consistently found a place in the annual financial plan. Since 2006, for example, the tendency has been to focus on the exemption threshold for personal or individual income in the budget. The adjustments in the threshold have had the effect of reducing the amount of income exposed to the prevailing marginal tax rate with the consequence that the tax liability for all individual taxpayers has been lowered with every adjustment.

In 2011, the administration also changed the marginal tax rates for commercial and non-commercial companies. Commercial companies had their rates reduced from 45 to 40 per cent while the non-commercial companies saw their rates decline from 35 to 30 per cent. During that year too, the exemption threshold moved from $35,000 to $40,000 per month. Now the administration has modified taxes on personal income and on the property of individuals and businesses. The concessions given would undoubtedly register favourably on the minds of taxpayers since they provide relief to them for the most part. On the face of it, the concessions appear to favour the poor.

Smokescreen

Yet, the concessions to the poorer taxpayers might be a smokescreen to hide the highly favourable benefits that will accrue to wealthy individuals from the changes in both the income and property taxes. The 2013 Budget proposes to reduce the marginal tax rate by about 10 per cent from thirty-three and one third percent to 30 per cent. This means that all taxpayers, including the wealthy ones, will reduce their tax liabilities too by an average of 10 per cent. When inflation is applied, the real reduction amounts to about six per cent. So, in reality, the poorer individuals enjoy no greater tax benefit from the concession made on income taxes than the wealthy individuals.

However, the higher-paid individuals save more that the lower-paid individuals from the concession. The projected savings from a reduction in the marginal tax rate when expressed as a per cent of income is greater among higher paid individuals than among the lower paid taxpayers. For example, a person earning $60,000 per month enjoys a tax savings that is equivalent to about half of one per cent of his or her gross income. On the other hand, a person earning $160,000 saves in excess of two per cent of his or her gross income as a result of the reduction in the marginal tax rate. As such, contrary to the impression carried in the budget speech, the adjustment in the tax rate creates a façade about favourability in its application.

Research

The property tax raises its own set of circumstances. It is not clear how many low-income persons have property that exceeds $7.5 million in net value. Based on the definition used for low-income housing, not many poor individuals would have net property that exceeds the existing threshold of $7.5 million. Even if they did as a result of inheritance or some other circumstances, the numbers might not be that large. To make the case definitively however, some research would be required to establish the individual income levels and the property values that correspond to each income level.

What is clear however, the wealthier persons stand to benefit enormously from the changes in property taxes. Under current rules, a person with property of net value of $40 million, the new exemption threshold, pays about $344,000 in taxes. Under the new rules, that person now has to have property of a net value of $86 million to pay the same amount of taxes that they were paying before the changes. Just to put the matter in perspective, Guyanese would have to have property worth in excess of US$200,000 to pay property taxes, and in excess of US$400,000 to pay the amount that they currently pay. It would indeed be an eye-opener to see the number of Guyanese who would exceed that valuation threshold. Consequently, it would be interesting to know the process used by the administration to arrive at the exemption threshold.

Tantalising

The 2013 budget is quite tantalising in the concessions that it makes to individual taxpayers. The lower tax liability creates the illusion of the lower-paid Guyanese being favoured over the higher-paid Guyanese. That is not the case as higher paid Guyanese are able to enjoy a higher return from the tax concessions than their lower-paid counterparts. The property tax concessions too are clearly oriented towards the well-off who were likely to have higher property valuations than the poorer Guyanese.