We returned to our places, these kingdoms

But no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation

With an alien people clutching their gods

Eliot, “The Journey of the Magi”

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Yeats, “The Second Coming”

It might be paradoxical and ironic to post-colonial thought, but it is very significant and not surprising that those lines of poetry from TS Eliot and WB Yeats proved to be important in the development of modern African literature. Not only were they a part of the rise of modern Western poetry at the time when they were written, but they reflect a picture of the world as seen by those poets just as they reflect a similar picture of African society at a parallel period as seen by the founder of modern African literature.

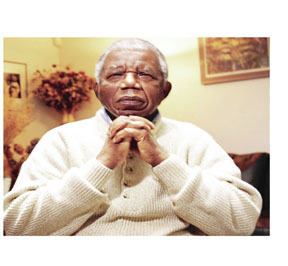

We are indebted to Albert Chinualumogu Achebe (1930 – 2013) for African literature as it is known to the world today. He was born in Ogidi, Nigeria, on Nov 16, 1930 and died on World Poetry Day, March 21, 2013.

We are indebted to Albert Chinualumogu Achebe (1930 – 2013) for African literature as it is known to the world today. He was born in Ogidi, Nigeria, on Nov 16, 1930 and died on World Poetry Day, March 21, 2013.

Critical consensus recognises a single work of fiction, Achebe’s first novel Things Fall Apart, published by Heinemann in London in 1958, as the opening chapter in the rapid development of this literature. After producing that gateway to acceptance, publishing and recognition, the highly encouraged Achebe’s further work as producer, editor and later as mentor, was additionally responsible for other works being published and the wider audience becoming comfortable with and impressed by the new phenomenon of African literature in English. This escalation led to the African Writers Series by Heinemann and to the appointment of Achebe as its editor. The publishers were emboldened by the early success to expose many other new writers and the writing itself, not to mention other publishing houses and an enlarged audience.

Things Fall Apart created African literature in English at a time when its author had virtually no models to guide him and such a thing as the African novel was unknown to international publishers, most of whom were even suspicious of it. Few would take the risk of pioneering unknown writers in an unknown field and a skeptical market. Then there is the role played by the fact that Achebe quickly produced other novels which helped to drive the march of the literature forward. He followed up with No Longer At Ease (1960) and Arrow of God (1962). His other famous novel is A Man of the People which came later. Furthermore, the brand of writing done by this author in English, and its study and challenging of West African society, influenced the waves of work by both East and West African writers who followed him.

Things Fall Apart has therefore been the single most import work in African literature. It is still the best known, still stands as practically the face of African writing; has been the most sold and most widely read, having been translated (according to Wikipedia) into some 50 languages.

Having said that, it must be pointed out that Achebe’s first novel was not the first work or publication in African literature, which was actually in existence long before that. One of the well-known and original works was The Palm Wine Drinkard by Amos Tutuola published in 1952. That was the pioneer work of fiction. Moreover, there was already the unfathomable store of literature in the African oral tradition such as the Ifa corpus, the Ewi Egungun, the satirical Udje, the mythology, and the grand store of folktales. In fact, it was these, in particular the myths and rituals that informed Tutuola’s work, written in a variety of English shaped by the syntax and consciousness of the author’s native language.

But while these preceded him, they were not the models used by Achebe. He had decided to write in English and to break into mainstream Western literature with forms it could understand and that could project the African consciousness and African social realism to the world. It was what Achebe produced and the follow-up work he did, not Tutuola, that made that breakthrough and unleashed the literature in all its forms. A later novel by Tutuola, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, did not get close to the success of The Palm Wine Drinkard, but the gateway opened by Achebe also admitted widened interest in Tutuola as well as in the great range of oral literature.

Neither was Achebe alone in leading the great charge of African literature in the 1960s. There were other workers in that vineyard and other movements that made the world take notice. Other Nigerians and Ghanaians were in the frontline, notably poets and playwrights: Wole Soyinka, John Pepper Clarke, Kofi Awooner (formerly Awooner Williams) and Ama Atta Aidoo. From other parts of Africa were such leaders as poets: Leopold Sedar Senghor and Dennis Brutus. Soyinka was to join with Senghor in the Negritude movement arising out of Paris and including West Indians such as Lèon Damas and Aimè Cèsaire.

But what was most telling about Achebe’s contribution were, apart from the timing and the doors he opened, the literary forms, the political and social significance of the (then) new work. Thomas Hardy’s poem “The Darkling Thrush” ushered in the new twentieth century with the bleakest possible picture. That was well in keeping with how the poets saw the world inhabited by flawed and frail mankind. The first two decades of the century, which already included a world war, were darkened by totalitarianism, lack of faith, lack of direction and rising imperialism. The poets responded with new forms of verse that departed from earlier styles and introduced modernism and versification known as modernist. This was all announced by Eliot’s The Waste Land in 1922.

Several countries in West, East and Central Africa were experiencing comparable turmoil in the 1950s. This included the experiences of colonialism, troubled race relations, clashes of culture, crises in traditional life, movements of nationalism, political awareness and moves towards Independence. Achebe was a writer and broadcaster at the Nigerian Broadcasting Service, and university Professor with a very keen allegiance to his traditional Igbo roots in South Eastern Nigeria where he was born. But his superior academic ability had ensured that he had a sound English education from secondary school to University College, Ibadan. He clearly appreciated the likes of Eliot and Yeats and the state of the world they wrote about. The state of his native Nigeria did not escape him either, and he was moved to write about it, challenging things that people took for granted or accepted without question while resenting some colonial attitudes.

Thus, he named his first novel Things Fall Apart, taking it from Yeats’ poem “The Second Coming” about anarchy and loss of control – “things fall apart, the centre cannot hold”. He wrote about the colonising of Nigeria and the devastating and tragic effects on the people and their traditional way of life. It was the coming of the English with their Christian religion and the confrontation with the old Igbo civilisation and religion. The novel is the tragedy of its hero Okonkwo, but also that of an old unbending Igbo culture. Achebe admitted that he wrote to celebrate his culture and to hail his country that was moving into nationhood with Independence from Britain on the horizon. But he also saw a dilemma because while he wrote very ironically about what colonisers saw as the “pacification of the primitive tribes of the Lower Niger” he also highlighted the weaknesses and inflexibilities of the traditional practices.

Achebe once said in a lecture in Jamaica that those critics who read his work as “a clash of cultures” are “illiterate”. It sounds like a similar line taken by Soyinka whose play Death and the King’s Horseman is a similar study of his Yoruba dilemma. Achebe’s second novel No Longer At Ease takes its title from Eliot’s line “no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation”. The protagonist Obi, a young man who completed his secondary education with high achievement enters the civil service and encounters corruption. His own tragic dilemma is that his family and kinsmen in the tradition of colonial life all expect it as a duty from him to profit from corruption for their benefit. Colonialism and independence and all the worst inheritances leave his nation “no longer at ease”.

Arrow of God returns to traditional religion in Nigeria and is a study of a priest Ezeulu struggling with hubris and the tragic outcomes of colonial impositions. The title alludes to his personal devotion, so deep and true that it moves straight and unwavering as an arrow, but like an arrow, causes injury at the same time. A Man of the People is a work of social realism similar to No Longer At Ease with its focus on an independent nation’s corrupt politics. The hero encounters Chief the Hon Nanga a seasoned and corrupt politician with a strong constituency of grassroots support.

Achebe drew on his own background growing up in the traditional setting but with a father who had converted to Christianity and an education that suppressed his native culture and language. With his University of Ibadan training (at that time University College, a satellite of University of London) he was fully grounded in English Literature and well appreciated the English language in a manner similar to Derek Walcott. He did not see it as a colonial imposition and was able to use it to the advantage of African literature. Out of this Chinua Achebe denounced colonialist prejudice. He looked critically at his nation and his people while glorifying them along with the Ibo civilisation and creating modern African literature.