By Basdeo Mangru

The abolition of slavery in1834, and the premature termination of apprenticeship four years later, created considerable concern among the planting interests regarding the reliability and regularity of the Creole workforce. Cognizant of large areas of unoccupied lands on the Guianese littoral, they feared that labour would abandon the plantations and adopt the wandering life of the Amerindians. Such a movement could result in both “industrial and personal collapse.”

Accordingly, some planters adopted strategies both to anchor workers on their estates and to continue sugar production. They reduced wages, increased the price of land, prevented squatting on Crown Lands, withdrew customary food allowances, cut down fruit trees and prohibited hunting and fishing. Some introduced new technology to obviate their dependence on manual labour; others with limited resources adopted the Metairie or share-cropping system. When these efforts failed, they turned more and more to immigration “to sustain the cultivation, arrest the fearful depreciation in the value of all landed property, and to prevent the abandonment of the Colony.”

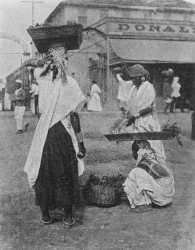

The planters tapped a variety of sources — the overpopulated West Indian islands, West Africa, Southern United States, the Portuguese Atlantic Islands, Malta, Europe, China, India – in their quest for a labour force that was cheap, docile, reliable and amenable to discipline under harsh, tropical conditions. These sources were tried with varying degrees of success until India answered their needs. Basically, there was a two-fold aim in immigration: to create competition for jobs thereby reducing wages, and to prevent a powerful labour combination against management by diversifying its cultural and ethnic composition. In short, the planters wanted to multiply the labour force and divide it as well.

The immigration schemes of the planters, who were accustomed to a mentality of coerced labour, were scrutinized in the Colonial Office which realized that such schemes could lead to the reintroduction of slavery in another form. Accordingly, it adopted measures to prevent restriction on liberty for “Freedom of labour is the general principle and restriction should be the exception.” On the other hand, slave emancipation was an experiment geared to demonstrate that sugar could be produced as cheaply and efficiently with free labour. The success of the experiment depended on the survival of the plantation. The critical state of the industry influenced the Colonial Office to grant five year contracts to enable John Gladstone, owner of Plantation Vreed-en-Hoop and Vried-en-stein, to introduce Indian labour.

On January 4, 1836 Gladstone, an absentee proprietor and father of England’s future Prime Minister, William Ewart Gladstone, wrote a letter to Gillanders, Arbuthnot and Company, a Calcutta firm recruiting and exporting laborers to Mauritius in the Indian Ocean. He asked for 100 able-bodied Indians on contracts for between 5 and 7 years. Gladstone’s letter detailing the attractive features of plantation life highly exaggerated the truth. The letter promised light work, comfortable dwellings, abundance of food, legal protection, free education, free medical attendance and religious freedom. The letter skilfully omitted the penalties for non-completion of work or for other infringements of the immigration ordinances.

The firm envisaged no difficulty in procuring such labourers, “the natives being perfectly ignorant of the place they agree to go to, or the length of the voyage they are undertaking.” This reply paved the way for the fraud and deceit which permeated the recruiting system. According to John Scoble, the vigilant secretary of the Anti–Slavery Society, it permitted “every scoundrel in India to kidnap and inveigle into contracts for five years, in a distant part of the world, the ignorant and inoffensive Hindoo!” The stage was now set for Indian indentured workers to labour under conditions bordering on slavery.

Of 414 Indian immigrants conveyed by the Whitby and the Hesperus (owned by Gladstone) 18 died in transit, leaving 396 survivors, including 22 women. Nearly one-half of this first batch, the ‘Gladstone Experiment,’ comprised ‘Hill Coolies’ (Dhangars, Mundas, Oraons, Santals, Kols,—generally referred to as ‘Junglies’) from the Chota Nagpur plateau, about 300 miles from Calcutta. Considered docile, simple, happy contented and hardworking, they lived an isolated life protected by dense forests which made transportation and communication difficult. In 1765 when Bihar, of which Chota Nagpur was a part, came under British rule, speculators moved into the region, purchased estates, rackrented the peasants and forced them to seek employment in the plains. Unscrupulous recruiters exploited their plight and recruited many for the sugar colonies.

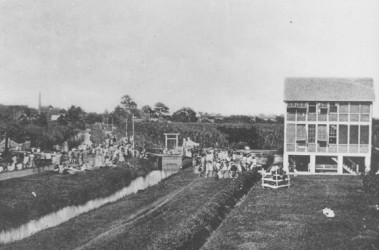

On May 5, 1838 the Whitby landed in Berbice and the Hesperus in Demerara. Within a week of their arrival, Indians were dispatched to their respective plantations – Vreed-en-Hoop and Vried-en-Stein (owned by Gladstone) and Belle Vue (Andrew Colville) in West Demerara, Anna Regina in Essequibo, and Highbury and Waterloo (Davidson, Barkly and Company) in Berbice. Except on Gladstone’s estates, Indians were lodged in barrack-like structures (called logies) which measured about 100 feet in length and 20 to 25 feet in width. In Berbice the structures were smaller.

Unlike the slaves, Indians were assigned to plantation work without a ‘seasoning’ or acclimatization period. The contract required them to work from sunrise to sunset, 7 to 9 hours a day, 6 days a week. They were expected to complete a task each day before returning home. The task, however, was judged by what a stalwart creole worker could complete in the specified time. It was thus difficult for an unacclimatized worker to complete the task. Field labourers were paid $2.50 a month, which was less that the 32 cents a day paid to the ex-slaves. Besides supplying Indians with rations, the planters allowed them to cultivate small kitchen gardens.

Not long after the arrival of the “Gladstone Coolies,” Governor Henry Light (1838-1848) reported that they were “supplied well, lodged well, and though on limited wages in comparison with free labour, yet are as carefully protected from oppression, and their complaints redressed as speedily as those of other labourers.” He described Indians on Gladstone’s properties as “a fine healthy body of men – they are beginning to marry or cohabit with the Negresses, and to take pride in their dress – the few words of English they know… proved that ‘Sahib’ was good to them.” This statement about cohabitation was highly exaggerated as only one or two cases were reported.

The real plight of Indians was exposed by the anti-slavery newspaper, the British Emancipator, which reported on January 9, 1839 several cases of ill-treatment and flight from Vreed-en-Hoop and Belle Vue. Two Indians, Jummun and Pulton, who fled from Belle Vue, were never seen again, though the bodies of two strange men were discovered at Mahaica, East Coast Demerara. An Indian girl of ten was reportedly raped and killed. A school teacher, Berkley, who spoke out against ill-treatment, was driven out of Belle Vue without payment of salary.

These revelations produced an investigation by Scoble and others of the Anti-Slavery Society. Scoble had visited the colony three years earlier to inquire into the conditions of workers under the system of apprenticeship. This investigative body unearthed maltreatment of Indians at Vreed-en-Hoop and Belle Vue especially. “To detail the whole of the iniquities practiced on the wretched Coolies, remarked Scoble, “would fill a volume.” Dr William Nimmo, Medical Attendant at Belle Vue and a relative of Gladstone, had reportedly struck an Indian patient with a horsewhip and had also inflicted corporal punishment on several others. The sick-house (hospital) was so filthy that the Court of Policy, the colony’s legislative body, ordered the immediate removal of the inmates to the colonial hospital. William Molseley, Agent for Immigrants, produced a pitiable picture of the plight of the patients: “I never saw such a dreadful scene of misery in my life as is now to be seen in the sick-house. I have been in a great many hospitals on various estates for the last twenty years; but I never saw such a melancholy scene.”

The planter-dominated Court of Policy, anxious to remove obstacles in the immigration process, responded by appointing a commission of enquiry. Details from the inquiry and subsequent court proceedings showed that five Indians had run away to Berbice from Vreed-en-Hoop. They were apprehended, confined temporarily in the hospital, tied to a post and, in the presence of fellow workers, flogged with a cat-o’-nine tails by the interpreter, Henry Jacobs, a Eurasian. Afterwards, ‘salt pickle’ was rubbed on their backs. Jacobs was convicted, fined ₤20 and sentenced to a month’s imprisonment. He was likewise punished for assaulting two other Indians, and for extorting $28.50 from 20 others who paid to avoid being whipped.

Such gross ill-treatment and exploitation reflected poor vigilance by management. Accordingly, Lord Brougham, a powerful orator and member of the House of Commons, and the Anti-Slavery Society denounced the failure of the Colonial Office to provide adequate legislative safeguards. As a result of such criticism, the British government, if it were to live up to its humanitarian reputation, had no option but to suspend immigration from India on July 11, 1839.

Subsequently, the Court of Policy passed a bill, which the Colonial Office promptly disallowed, to raise ₤400,000 for immigration purposes. The planters then formed a voluntary subscription society in 1840 to introduce immigrants by private enterprise. The attempt failed to attract a large pool of labour for various reasons. Two years later their attempt to reduce wages to cut plantation expenses produced a general strike and a continued movement from estate to villages.

Meanwhile between December 1842 and January 1843 the immigrants’ five year contracts were expected to expire. When Indians realized that ships would not be available to repatriate them, many refused to work or accept rations. Eventually two ships, the Louisa Baillie and the Water Witch were chartered to convey them to Calcutta. Altogether 236 immigrants embarked, 60 remained, 2 absconded soon after arrival and 98 perished. Thirty repatriates on the Louisa Baillie died on the five month’s passage to India mainly owing to a lack of proper clothing.

Considerable attention was given to the savings of the repatriates. While some Indians refused, or were reluctant, to declare their savings, individual savings ranged from $4 to $483. Taking into consideration that monthly the wages for field labour were $2.50 (or $150 for 5 years, Indians must have exercised considerable thrift and industry. Some had probably performed additional work for extra pay, reared feathered stock, cultivated small plots of land or worked in private enterprise as well. The failure of some to save was attributable to drinking, payment for sexual favours or theft of savings.

Generally, the relationship between Indians and Blacks was not antagonistic. In fact, a few Blacks were even sympathetic to the plight of Indians as evidenced from their testimony before the inquiry commission. Although Indians lived in separate quarters, there was some interaction between the two racial groups in the fields. At this early period, Indians did not seem to pose any significant threat to the bargaining power of the Blacks although, understandably, there was a degree of resentment at their presence.

The introduction of the first Indians in the Caribbean showed negligence by estate authorities and inadequate safeguards by the Colonial Office. As guardian of the unrepresented masses, the Colonial Office failed to enforce regulations for a compulsory period of acclimatization and adjustment as was customary under slavery. This was perhaps the principal reason for the high mortality – 67 deaths in 18 months, or nearly 17% of those introduced. The doctrine of trusteeship was thus honoured more in the breach than in the observance. But the steady industry and productive capacity of Indians as plantation workers led the planters to clamour repeatedly for their reintroduction. That Indians had saved the sugar industry from collapse after emancipation can hardly be refuted.