The Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 against colonial domination in India had been for a long time the subject of much controversy and debate and had produced more literature than any other single event in modern Indian history. To some British officials, it was “a momentary ripple on the placid waters of the British Raj.” To Indian nationalists, it was the First Indian War of Independence. Socialist thinkers, like Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, also supported the Indian view. Charles Canning, Governor-General of India, admitted that it was “more like a national war than a local insurrection.”

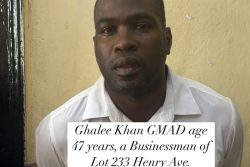

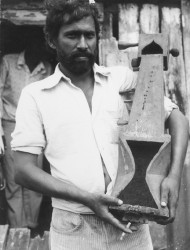

nineteenth-century sarangi which had been handed down to him (photo, 1976)

The Mutiny was the product of the accumulated grievances of Indians against the exploitative tentacles of the British East India Company (BEIC). A significant factor was sepoy (sepoys were Indian soldiers in the army of the BEIC) discontent, the overwhelming majority being Brahmins and other high castes. A large contingent of the Bengal Army (which alone was involved) comprised soldiers from Oudh, and they formed a coherent and homogeneous group within the army. They and other sepoys resented the lack of promotion, high taxation, low pay, insults from junior British officers, and the mandatory requirement for new recruits to serve overseas which meant loss of caste and grave social degradation.

Besides sepoy grievances, Indians resented British economic exploitation and the destruction of India’s traditional economic base. Peasants, artisans, educated Indians and traditional zamindars/talukdars (landlords) were impoverished. Conservative elements in Indian society denounced the activities of Christian missionaries who openly attacked Hinduism and Islam, and British interference in their religious practices. British arrogance and the annexation policy of Governor-General Lord Dalhousie also produced discontent. Muslim pride was hurt when the last of the Mughal Emperors, Bahadur Shah, was forced to quit the historic Red Fort for a humbler residence at the Qutab Minar.

By 1857 the ingredients for a revolt were ready. All that was needed was an immediate issue, a spark. The episode of the greased cartridges provided the spark, and the Mutiny gave Indians the occasion to revolt.

In 1857 the British introduced the new Enfield Rifle in the Bengal Army. The cartridges, greased with a mixture of both cow and pig fat, had to be bitten off prior to loading. The sepoys, both Hindus and Muslims, were enraged as they were convinced that the British were deliberately trying to undermine their religion. Although the cartridges were withdrawn, the suspicion could not be easily dislodged. The revolt began on 10 May 1857 at Meerut, a military cantonment about 35 miles north of Delhi which represented symbolically the remains of Mughal power and glory. It spread across the whole of northern India from Delhi to Bihar, the main centres of activity being Delhi, Lucknow, Jhansi, Kanpur and Shahabad.

By July 1858 the Mutiny had collapsed for a variety of reasons. The British had such fire power and confidence in their ability to smother it that their success was never in doubt. In terms of strategy and tactics, British commanders were far superior to Indian commanders. Although the mutineers and those who joined them had an overwhelming numerical superiority, they failed to utilize their initial advantages. Consequently, the uprising was isolated and uncoordinated, and their lack of modern weapons and a plan of action proved disastrous. Perhaps the main factor for its collapse was Indian disunity. Rulers of princely states, zamindars, merchants and modern educated Indians refused to join for various reasons.

During the uprising, the press in Guyana devoted considerable space to discussion about its causes. The Colonist, a pro-planter newspaper, described it as a “brahmanical conspiracy,” to oust the British from India. The pro-government paper The Royal Gazette, saw it as “an exclusively military conspiracy.” It advised that the “most fitting punishment” would be transportation, with their families, to “some distant clime and never to be permitted to return.”

In October 1857 The Colonist disclosed that the British Guiana government had applied to the BEIC for 25,000 sepoys to be transported to the colony. This report was apparently based on a memorial to the BEIC by Stephen Cave, Deputy Chairman of the West India Committee, the planters’ powerful lobby at Whitehall. It envisaged that when the revolt was suppressed, a small portion of the defeated mutineers could be utilized as agricultural workers in the West Indies

The proposal received the enthusiastic support of the planters. A year earlier the anti-Portuguese riots had exposed their vulnerable position in the society. This position became more precarious especially as it was rumoured that “when they [the blacks] were done with the Portuguese they would attack the whites. The introduction of sepoys could, besides providing labour on estates, act as a counter to the Creoles (blacks) especially as they possessed military training.

Nevertheless, the most crucial question was whether the planters could rely on the sepoys, who had caused such havoc in India, either as a reliable labour force or as providing a strong buffer. Could not such a move be fraught with danger? Peter Rose, a prominent planter representative, warned that if sepoys were imported, the planters “would see, from one end of the Colony to the other, nothing but the ruins” of sugar estates. The crux of the matter was that the sepoys would be unarmed and would comprise only those who took no active part in the revolt but who deserted their posts under pressure. But the scheme also envisaged the transportation of 1000 men sentenced to penal servitude for life for their role in the mutiny. They would be employed on public works, and on government penal gangs if found “refractory and unmanageable.” To minimize any chance of a revolt, plans were drawn up for the strengthening of the colonial garrison with white troops.

Besides providing an effective counterpoise, the scheme held out tremendous economic advantages. Hence the planters proposed to introduce 30,000 instead of the 10,000 originally proposed. Although the sepoys were not “professed tillers of the soil” they were accustomed to discipline and a disciplined labour force was considered a sine qua non to the survival of sugar.

Under the proposed scheme, the newcomers would be contracted for a stipulated period, paid wages at the current rates and denied the opportunity of ever returning home. They would be regarded as permanent exiles and not as convicts. The British Guiana government hoped that with their labour, the planters would be able to resuscitate cotton production. Moreover, the plan envisaged that the sepoys would be accompanied by their wives and children. Here the advantages were two-fold. The women would help to alleviate the disproportion in the sexes in the Indian camp while the children would do lighter tasks formerly performed by slave children. An additional advantage was that the BEIC would defray the passage expenses for sepoys; the planters would pay the cost of introducing the family but it would be recovered through a small deduction from their wages.

The planters’ high expectations were crushed with the terse dispatch from the Secretary of State for the Colonies that the Government of India had decided to send to the Andaman Islands the sepoys who were to be “transported” from India. A few months later the Queen’s Proclamation pledged countrywide amnesty. This amnesty was enthusiastically implemented by Canning. With the establishment of a penal settlement at Port Blair in the Andamans, the proposal to transport sepoys was doomed.

Nevertheless, there is strong evidence that some sepoys who actively participated in the revolt opted voluntarily to emigrate “to avoid a compulsory sea-trip to Port Blair.” During this upheaval in India, colonial emigration reached its apogee. The number dispatched in the 1857-58 season was the highest from Calcutta, and emigration officials suspected that sepoys were among the emigrants. The Mauritius Emigration Agent noticed “large bodies of a [physically] superior class of people” crowding his depot and offering to emigrate. George Campbell, Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal, toured the affected areas in 1858 and reported: “After much inquiry I am satisfied that the mass of the mutineer sepoys have not returned to their homes, and it is very difficult to find out what has become of them.”

Despite the failure to import sepoys, one cannot dismiss the possibility that a number of sepoys might have landed in Guyana as indentured labourers. There were two main explanations. First, it was not difficult for emigrants to conceal their identity because no determined effort was made to ascertain castes or names of emigrants. Secondly, the bulk of recruits were drawn largely from the affected areas. For example, the total of 31,184 recruits during the 1854-56 season suddenly jumped to 88,895 between 1857 and 1859 or an increase of some 185 per cent. Furthermore, in 1863 between 25 and 30 sepoys were reportedly involved in an attempted mutiny on board the Clasmerden bound for Guyana. The Emigration Agent believed that they concealed their identity at embarkation.

There was also strong evidence of sepoy implication in the 1872 Devonshire Castle Riots in the Essequibo, resulting in the death of five indentured workers. The Colonist rather dubiously claimed that Indians rose up “with the avowed object of murdering the whites and of playing on a small scale in British Guiana the part their country men played in the drama at Cawnpore, sixteen years ago.” The deposition of some of the eyewitnesses also added a measure of credibility to reports of sepoy involvement: “They were all fighting men. Some sepoys were among them.” The Royal Gazette not only made similar observations but hinted as to the possibility of a conspiracy. As expected, the police were exonerated in the shooting, but the Supreme Court found no conclusive evidence of sepoy complicity.

The Mutiny of 1857 produced profound changes in India. The power to govern the country was transferred from the British East India Company to the British government. Changes occurred in British administrative policies and in the British relationship with the people of India and the rulers of princely states. The British offer of clemency was geared to win the goodwill of its colonial subjects. Given this change in policy, Canning’s enthusiastic support of the amnesty and the opening of the penal settlement in the Andamans, the transportation of sepoys overseas no longer seemed necessary.

Disappointed at the failure to import sepoys, Guyanese planters redoubled their efforts to cope with the tremendous competition for labour in the main recruiting districts of India.