This article by Dr Chanderbali was first published by Stabroek News on May 5, 2006, under the caption ‘Indian indenture: Some reasons for immigrants repatriating and settling.’

By David Chanderbali

The Indian immigrants in British Guiana who had completed their first contract and had also fulfilled the five-year “industrial residence” requirement were entitled by law to free repatriation to India. The advantage of the free return passage was not taken by a majority of immigrants in the colonies more distant from their homeland. Between1842 and 1870, for instance, an average of 76 per cent of the immigrants in Mauritius, British Guiana, Trinidad, and Jamaica decided to settle in their respective colonies. By comparison, for the same years, of those who had sought employment in Ceylon, Burma, and Malaya, 80 per cent decided, for reasons undocumented, to return home at their own expense. Why the average 24 per cent in the more distant colonies decided to repatriate is also not easy to establish. The immigrants were not questioned before their departure from the colonies, and the Protector of Emigrants in India, although required by law to do so, seldom interviewed repatriating labourers. Even when they did, it was cursory and unsystematic. Nevertheless, regarding the Indian indentured immigrants in British Guiana the following reasons, either singly or multiple, would explain why a minority decided to return to India and the rest opted to settle in the colony.

For many immigrants, their expectations that were based on the recruiters’ promises had been too high, and they would have been disappointed when reality confronted them. For some immigrants, the shortage of marriageable Indian women, coupled with their apparent aversion to exogamous marriages, would have been a source of great discontent. That more men retro-migrated did not alleviate the sexual imbalance since more males than females continued to arrive in the colony. Other immigrants would have been overcome by the nostalgia of Mother India and the memory of a wife or an old parent whose funeral pyre his religion required him to light.

Those immigrants who had arrived weak and sickly and were able to strengthen themselves by better food and medical care could not have been overly daunted by the perils and uncertainty of the long voyage home. The belief in the loss of caste was probably inconsequential to many who repatriated. With the money saved, they could establish themselves in another community and keep their transmarine experience a secret, or, as many had actually done, give caste-dinners at which they were reinitiated, often in a higher caste.

A number of immigrants in the colony would have been dissatisfied as a result of the treatment received from medical officers. It was common practice for medical men to discharge immigrants from hospital before they were completely cured, and to this may be attributed a large percentage of the so-called idleness charges that were brought before magistrates. By the strict letter of the law, an indentured immigrant was bound to do his daily task of work if he was not in hospital or in gaol, and although the magistrate had a discriminatory power of declining to convict, if he believed the accused was physically unable to work, it would have been difficult for him, on account of the alleged malingering propensity of the East Indians, to decide, other than in extreme cases, against the expressed opinion of the doctor.

The immigrants’ perception of unfair dealing by the courts would have also influenced the decision to repatriate. Of the majority of immigrants who were weekly committed to gaol for breaches of contract, a very considerable proportion was convicted of neglect to do what they were physically incapable of doing. Even pregnant women were liable to punishment for neglecting to perform the ordinary task of work despite the fact that they pleaded their delicate condition in this respect, and were evidently, by their appearance, near their confinement. A sense of injustice about such convictions seemed a very potent cause for the prevailing discontent amongst the immigrants. Another cause for discontent was the fact that invidiously distinct positions in court were assigned to managers of estates. Some of them being Justices of the Peace were allowed to remain on the bench even during the trial of their own cases. It very often happened that a manager would in open court whisper to the presiding magistrate upon the subject of the case being tried and in which he was a complainant. Such behaviour would give the immigrants the impression of partiality, even in the case of a conscientious magistrate.

Finally, the East Indians experienced a social problem which would have persuaded a number of them to return to India. During the early days of immigration few of them had received even a modicum of education in British Guiana. They were, however, able to retain their religion, their social habits, and to some extent, their language. With their mixture of castes and religions and their different languages and dialects, they tended to become narrow in outlook and less prone to become cosmopolitan. Moreover, their contractual terms created a mentality and an atmosphere amongst them of a mere temporary stay in the colony. Consequently, the provision that the colonial government made for public education during the period of indenture tended largely to pass the Indians by.

Decision to settle

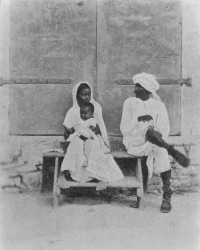

The Indian immigrants who chose to settle in British Guiana would have been motivated by one or a combination of the following factors. After ten years’ residence among jahaji bhais (ie brothers of the boat, as indentured shipmates affectionately addressed one another) and sometimes among kith and kin, and new alliances, the nostalgia that would have afflicted the immigrants would have dissipated. In the early years of indenture, they would have experienced the trauma of a contraction in the field of social participation. But with every new wave of immigrants landed on the estates, that field would have expanded to encompass a growing social circle comprising little Indias. All of this would have eased the pressure of living in a foreign country.

At the end of the tenth year also, many labourers had acquired a family and built their own home and owned livestock and other property. Those who had renounced their right to repatriation through commutation of their entitlement to a free passage would have added to their material acquisitions the compensatory parcel of land. All of this would have placed them in a position of comparative wealth and comfort instead of the comparative uncertainty they would have had to face upon returning to India.

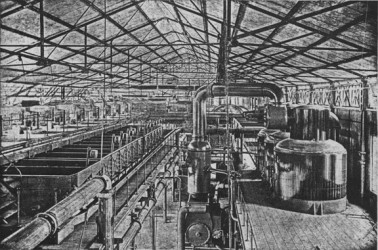

Generally, living conditions in Indian villages from which most of the labourers had been recruited were not up to the standard of the conditions prevailing on the colonial estates, even as early as the 1840s. Wage rates, too, were far lower. In India, around the same time, the average daily wage rate in terms of purchasing value was the equivalent of four cents; in British Guiana, it ranged between the equivalent of thirty and forty cents. Furthermore, in India, the riot had to contend with the vagaries of nature, often expressed in droughts and floods both of which often led to famine. There was also the rapacity of man – the money-lender or the landlord – both of whom customarily utilized their cunning to bind their victims into a lifetime of debt.

Those labourers whose first indenture had expired had acquired five years’ experience of their work; they would have become acquainted with their position in all its aspects; and would have been able to decide, according to their own practical knowledge, whether it would be advantageous for them to return to India or to remain in the colony.

For acclimatized and experienced labourers, there was competition among the planters for their services. Many employers were not content with offering the usual fifty-dollar bounty money to those who re-indentured, but also offered a bonus incentive of five and sometimes ten dollars. For the thrifty, this bounty money and the bonus, the equivalent of about a year’s income, became the nucleus of a fortune. It was thus that a number of labourers were able to invest in cattle and become milk vendors, and to enter the retail and later the wholesale trade. To a number of labourers, re-indenturing would be viewed as being better than the status of a free labourer, as it was the only way to ensure free medical attention, free hospital accommodation, and free living quarters. The temptation for them to re-indenture over and over again must have been irresistible.

Another possible motivation for settling concerned the implications accompanying the loss of caste. Before leaving India, the immigrants had been rigidly fixed in a stratified social system based on caste. But once they had crossed the kala pani (ie the black water) they lost all claim to their erstwhile caste, re-admission to which was achievable either by travelling to the sacred Indian city of Benares to wash seven times in the holy water of the Ganges or by giving lavish caste dinners and elaborate gifts to often unscrupulous priests. Initially, the popular belief among the immigrants was that failure to thus cleanse themselves was to invite divine retribution. However, towards the end of the nineteenth century and afterwards, the injunction on travelling by sea was widely discredited, and it was not applicable to all strata of Hindu society.

The immigrants’ ability to preserve their values and to practise their customs must be accorded considerable significance as a factor encouraging settlement in the colony. Despite the pervasive and socially and culturally destructive influences of the plantations, the immigrants managed to keep intact the central tenets of their cultural values which in later years were given elaborate expression. This they achieved mainly through their strong desire to use their own languages and through their tenacity to resist imbibing trappings of Western civilisation. The frequent visits by missionaries and other emissaries from India also tended to keep intact the umbilical cord that bound the immigrants to India. The practice of their culture, the availability of most of their native foodstuffs, the presence of a growing number of their compatriots, and the sight of masjids and mandirs on every estate must have made them feel, in a vicarious sort of way, that they were still in their native country.

For a number of immigrants there was the fear of the long voyage to India occupying 100 days or more and marked by their witnessing dozens of deaths. Chief among the causes for excessive mortality on board ship were the debilitated condition of some of the returnees; the deficiency of animal protein and fresh vegetables; and the damp condition between decks, which rendered the atmosphere unwholesome and conducive to disease.

Finally, there was widespread knowledge among the immigrants that suffering inevitably came to a sizeable portion of those who repatriated, especially those who did not have or could not find relatives in their native villages. Often adding to this problem was the fear of ridicule and shame in India that usually accompanied an inability to demonstrate material progress.

Despite these restraining factors it must be observed that throughout the period of indenture, pressures had been brought to bear upon the British government, the Government of India, and the colonial government of Guiana, most especially by the findings of various commissions of enquiry and by vociferous local and overseas critics, to enact protective legislation to safeguard the interest and welfare of the immigrants. Legislative enactments did not, of course, completely eradicate all evils in the system, but they did go a long way to alleviate some of the sufferings of the labourers to make life in the colony more tolerable, and consequentially encourage a very large number of immigrants to make British Guiana their home.