While on May 5th the 175th Anniversary of Indian Arrival was commemorated, there was another anniversary two days earlier that slipped by unnoticed. May 3rd marked the 178th year since the Portuguese first arrived in this country. Below we reproduce three articles written by the only authority on the Portuguese of Guyana, Professor Mary Noel Menezes, RSM, all of which had been published previously by Stabroek News. All the pictures are courtesy of Prof Menezes.

By Mary Noel Menezes, RSM

Previously published in

Stabroek News on May 4th, 2010.

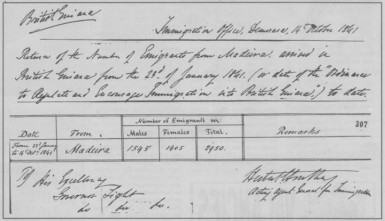

On 3rd May 1835, after a voyage of 78 days, the Louisa Baillie docked in Demerara with 40 Madeiran emigrants bound for Pln Thomas of RG Butts and for Plns La Penitence and Liliendaal of James Albuoy. Why did emigrants from a 286-mile island, Madeira, off the coast of Morocco migrate to a continental British colony on the northern tip of South America? Three factors made such a move a reality:

1. The approaching abolition of slavery throughout the British possessions creating a labour gap;

2. The long-standing alliance between Portugal and England;

3. The political, military and economic problems in Madeira in the 1830s.

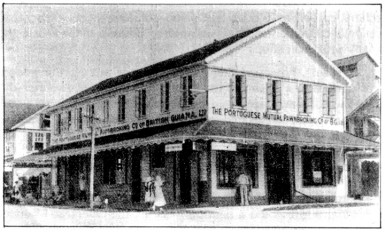

The building unfortunately burnt down on Christmas Day, 2004.

Sugar had been grown in Madeira since 1452 and by 1500 the island had become the world’s largest producer of sugar cultivated by the sturdy and hard-working peasant-farmer who, suffering from the economic depression and political troubles, was eager to emigrate. The first decade of the arrival of the Madeirans was a difficult one for them; disease and death plagued those years. At the same time strong objections against emigration were raised by the Madeiran civil and ecclesiastical authorities fearing the erosion of their labourers.

By 1845 most of the Portuguese had moved off the plantations, bought small plots of land and moved into the huckster and retail trade. In 1843 the first importation of goods from Madeira by the Portuguese was noted by both the Madeiran and Demeraran press. The Portuguese were long masters in the field of trade and the Madeiran emigrant brought with him this flair and expertise.

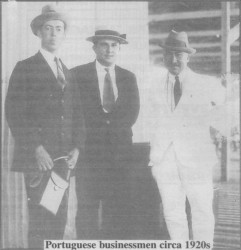

In the early years it was mainly in the rum trade that the Portuguese made their mark. By 1852 79% of the retail rum shops were owned by the Portuguese and they retained that monopoly well into the twentieth century. The end of the 1860s and the 1870s saw the Portuguese well entrenched in business. The roster of Portuguese entrepreneurs was extensive. Apart from being property owners, they were provision and commission merchants, spirit shop owners, importers, ironmongers, ship chandlers, leather merchants, boot and shoe makers, saddlers, coachbuilders, woodcutters, timber merchants, brick-makers, cattle owners, pork-knockers, charcoal dealers, bakers and photographers.

This commercial success of the Portuguese received high praise in the Royal Gazette.

The rise of the Portuguese in this colony from a state of most abject poverty to one of comparative affluence, and to the possession, in many instances, of thousands of dollars within the space of a few years, is one of the most remarkable occurrences in modern colonial history.

This unprecedented success of the Portuguese in business aroused the jealousy and animosity of the Creoles to such an extent that riots resulted, one especially violent one, the 1856 ‘Angel Gabriel’ Riots during which Portuguese shops were extensively damaged ‒ shops but not lives.

In 1858 the number of Portuguese in the colony was estimated at approximately 35,000 and mostly all were Roman Catholic. They brought not only their agricultural expertise but their faith as well. The Madeirans were profoundly religious; their religion they expressed with joy. Their religious festas were celebrated with joyful abandon and with much pomp and splendour. With the arrival of Portuguese-speaking priests the Catholic Church advanced rapidly. In 1861 Sacred Heart Church was built for the Portuguese and by the Portuguese. Other churches rose all over the country, along the East Coast and East Bank Demerara and in Essequibo.

Of all the religious customs transmitted by the Portuguese, the Christmas Novena continues to hold sway among Catholic Guyanese of every ethnic origin. Another Madeiran custom was the establishment of confraternities, guilds and societies for the relief of widows, orphans, the sick, unemployed, the elderly and the imprisoned, as well as for the education of the children of their members.

The Portuguese held on to their language throughout the nineteenth century. A number of Portuguese newspapers kept the Portuguese in touch with events in Madeira and in the colony: Voz Portuguez, O Lusitano, Chronica Seminal and The Watchman, among others. Portuguese schools were established for both boys and girls.

Together with other amateur and professional groups the Portuguese entered the cultural stream of music and drama in British Guianese society. Plays and concerts were held at the Assembly Rooms and at the Philharmonic Hall. Noted for their musical bands in Madeira the Portuguese formed the Premeiro de Dezembro band which played at every festivity in the colony and regularly on the sea wall, and in the Botanic and Promenade Gardens, the Town Hall and the Assembly Rooms.

The Portuguese were also prominent in the world of sports: in boxing, cricket, cycling, rugby, football, tennis, hockey, racing and rowing. In 1898 the first cycling club, the Vasco da Gama Cycling Club, was formed by the Portuguese. In 1925 the Portuguese Club was founded and nurtured famous tennis players of the day. Indeed, the Portuguese worked hard in their business world but they also played hard. In music, dance and sport, they acquitted themselves well.

However much the Portuguese added to the cultural dimension in music, drama and sport, their entry into the political field took them much longer.

First, there was the language barrier; secondly, the majority of the Portuguese men were not naturalized British subjects and thirdly, the government constantly cautioned the Portuguese “not to meddle with politics” but stick to their business. Not until 1906 did the Portuguese run for office, FI Dias and JP Santos winning seats in the Court of Policy and Combined Court. However, although the Portuguese had gained a political foothold, they were not at all welcomed with open arms into the colonial government.

By the turn of the century the Portuguese had created their own middle and upper class. They were never accepted into the echelons of white European society though they themselves were European. Much less did they “bolster white supremacy.” The rapid economic progress of the Portuguese, their strong adherence to the Catholic faith and their clannishness bred respect but never wholehearted acceptance among the population either in the nineteenth or twentieth century. With the upheavals of the 1960s and events in the 1970s many Portuguese crossed the ocean in search of another EI Dorado in the north, maybe in the spirit of the early Portuguese explorers who lived to the hilt the motto of Prince Henry the Navigator: “Go farther.”

Some preliminary thoughts on Portuguese

emigration from Madeira to British Guiana

By Mary Noel Menezes, RSM

The article below appeared in Stabroek News of May 7, 2000 having been reprinted courtesy of Kyk-Over-Al, December 1984.

In the 1830s and into the 1850s Portugal was undergoing a series of crises ‒ recurring civil wars between the Constitutionalists and the Absolutists, the repercussions of which were felt in Madeira. Many young men jumped at the opportunity to get out of Madeira at any cost and thus evade compulsory military service which was necessary, as Madeira was considered part of metropolitan Portugal.

Also, more and more, poverty was becoming a harsh reality of life on the thirty-four mile long, fourteen mile-wide island of 100,000 inhabitants. During the first decade of the nineteenth century life for the peasant, the colono who worked the land for the lord of the manor, had become even harder.

Madeira had been discovered in 1419 by Joao Goncalves Zarco under the auspices of Prince Henry, the Navigator, and by 1425 it had been settled. Prince Henry, son of Joao 1 of Portugal and patron of exploration, an unusually far-seeing and intellectual prince of his age and of many centuries beyond, was responsible for the introduction of the sugar-cane from Sicily to Madeira.

By 1456 the first shipment of sugar was sent to England, and by the end of the century the burgeoning sugar industry was helping Madeira to play a prominent role in the commerce of the period. Bentley Duncan claims: “By 1500, when Madeira had reached only its seventy-fifth year of settlement the island had become the world’s greatest producer of sugar, and with its complex European and African connections, was also an important centre for shipping and navigation.”

After 1570 the sugar trade began to decline as it faced competition from the cheaper and better-refined Brazilian product. Also the industry had been bedevilled by soil exhaustion, soil erosion, expensive irrigation measures, destruction by rats and insects, and ravaging by plant diseases.

As sugar declined in international trade the wine trade took precedence. Here again Madeira owed its name as a famous wine-producing country to the enterprises of Prince Henry who introduced the vine from Cyprus and Crete. The ‘Madeira’ of Madeira took its place with the port of Oporto on the tables of the world. It was soon discovered that the rolling of the ship added to the rich quality of the wine, and in the 17th and 18th centuries no ship left the island without a large consignment of pipes of Madeira for the West Indies and England, the largest consumers.

In the 19th century wine was being shipped from Madeira to the United States, England, the West Indies, the East Indies, France, Portugal, Denmark, Cuba, Gibraltar, Newfoundland, Brazil, Africa and Russia. By the late 19th century St Petersburg, Russia, vied with London in its consumption of Madeira.

But as with the sugar industry so too with viniculture. The vines were often demolished by diseases. In 1848 the oidium ravaged the plants, and by 1853 vine cultivation was almost totally abandoned. Twenty years later, the phylloxera, which also nearly ruined the French wine industry, crippled the vines.

The Madeiran peasant, in particular, owed his existence and that of his family to his job as a sugar-worker, a vine-tender or a borracheiro (transporter of wines in skins). No wonder when catastrophe continuously hit those crops, “the peasant, descending from the sierra with his bundle of beech sticks for the beans, and occasionally stopping to rest at the turns in the paths, casts his glance at the sea horizon and, in spite of himself, begins to feel the winged impulse to disimprison himself in search of lands where life would be less harsh.” (de Gouveia)

Thus the Portuguese emigrant who came to British Guiana was the inheritor of a more than 300-year legacy of sugar production and viniculture. He was also a “thrifty husbandman of no small merit” (Koebel) utilising every inch of available space of the terraced hillsides to grow peas, beans, cauliflower, cabbage, potatoes, carrots, spinach, pumpkin, onions and a vast variety of fruits.

Thus it is surprising to read in Dalton’s history that agriculture was not the forte of the Portuguese! What is even more surprising is the somewhat grudging concession made to the commercial enterprise of the emigrants. Significant among the reasons given for their meteoric rise to prominence in the retail, and later the wholesale trade in British Guiana, is the over-emphasis on the “preferential treatment” accorded them by the government of the day.

Thus it is surprising to read in Dalton’s history that agriculture was not the forte of the Portuguese! What is even more surprising is the somewhat grudging concession made to the commercial enterprise of the emigrants. Significant among the reasons given for their meteoric rise to prominence in the retail, and later the wholesale trade in British Guiana, is the over-emphasis on the “preferential treatment” accorded them by the government of the day.

It was “the patronage of the European elite [which] was the spark that ignited Portuguese initiative and secured ultimate success” (Wagner). To continue this train of thought ‒ the government and planters regarded the Portuguese as allies against the Creoles. Yet it seemed that this European patronage boomeranged as later one is told that as the commercial power of the Portuguese grew they “became a threat to European elite’s dominion.”

One is left to conjecture whether the Portuguese in British Guiana would ever have risen in the mercantile trade had not the government and planters paved the way for them. Yet an investigation of Portuguese-Madeiran history indicates a long familiarity with trade and the tricks of trade. The Madeirans were heirs to a dynamic trade system that had its roots in 14th century Portugal when Lisbon was the important Atlantic seaport carrying on a vigorous trade with the Orient and Europe.

Nineteenth century sources reveal an incidence of shopkeepers on the island with writers commenting caustically on those “wily creatures” (shopkeepers) imbued with the spirit of swindling. One observer on the island wrote: “They can work like horses when they see their interest in it, but they are cunning enough to understand the grand principle of commerce, to give as little, and receive as much as possible.” A plethora of shops on the island, some of which date back to earlier centuries, attests to the fact that the Madeirans were no novices in business.

The British presence in trade and industry was ubiquitous but by the eighteenth century native jealousy had become very overt. By 1826 Madeirans were strongly objecting to “the almost monopoly of trade of the island in the hands of British merchants.” (Koebel) Possibly then the Madeiran merchant in British Guiana might have argued that the British merchants there owed him patronage in return for the privileges their counterparts had been receiving in Madeira for over two centuries!

The Madeiran emigrant then, did not arrive in British Guiana devoid of everything but his conical blue cloth cap, coarse jacket, short trousers and his rajao (banjo). As did all other immigrants he brought with him a background history in agriculture, a flair for business, as well as the culture and mores of his island home, a replica of the mother country, Portugal.

He brought with him, not only his family, but in many cases his criado (servant), his deep faith, his love of festivals, his taste in food, the well-known pumpkin and cabbage soup, the celebrated moorish dish, cus-cus, the bacelhau (salted fish), cebolas (onions) and alho (garlic). These tastes and many other customs became incorporated into the life of the Guianese.

Very early the Roman Catholic faith was carried throughout the country and wherever the Portuguese settled churches were built; the major feast days were celebrated, as they were and still are in Madeira, with fireworks and processions. As the Register of Ships notes, throughout the nineteenth century ships plied between Madeira and British Guiana, ships chartered by the Portuguese themselves, bringing in their holds cargoes of bacelhau, cus-cus, cebolas, alho and wine, as well as new emigrants.

The success and prosperity of the Portuguese within a short span of time and out of proportion to their numbers (in a total population of 278,328 in 1891 they numbered only 12,166 or 4.3 per cent), whether due to “preferential treatment” or not, brought in its train economic jealousy among the Creole population, erupting in violence within fifteen years of their arrival in the colony. Later, when the Portuguese began to oust the European merchant in the wholesale trade, they felt the brunt of European envy which manifested itself in many subtle and overt ways.

Though the whites grudgingly acknowledged the economic supremacy of the Portuguese, at no time did they accord them social supremacy or draw them into their privileged group. This attitude undoubtedly hurt and embittered the Portuguese who considered themselves Europeans. But this did not hamper them or cripple their expectations or ambitions. Although from the very outset the local authorities, both Church and State in Madeira, tried to dissuade their countrymen from leaving the island, the emigre returning with his earnings, on the other hand, encouraged his brethren to cross the Atlantic and find their E1 Dorado in Demerara.

Today it seems that “the winged impulse” has again overtaken the Portuguese, and many have crossed the ocean in search of another E1 Dorado ‒ in the north.