This subject was earlier approached in a publication The Walter Rodney Factor in West Indian Literature by Al Creighton and partly carried in ‘Arts on Sunday.’ What is included here, however, is updated, current material which benefits from new research.

He really had nothing to say

under the silence, least of all

about important topics

like poverty and politics,

why, as you’ll note

he never even wrote

a Rodney poem.

(Edward Baugh)

A week ago, June 13, 2013 was the 33rd anniversary of the death of Guyanese historian and political leader Walter Rodney who was killed by a bomb explosion in Georgetown on ‘Black Friday’ (June 13, 1980). This was recently recalled to public attention because of the anniversary, and also because the Government of Guyana announced their decision to hold a public inquiry into the circumstances of his death through an international commission.

This, of course, is of great and widespread political interest with further international repercussions. International groupings, including academics such as Jamaican historian/political scholar Horace Campbell took up the matter when South Africa decided to present the Tambo Award to Forbes Burnham for his anti-imperialist support of the struggle against apartheid and African liberation. Burnham was Guyana’s President and leader of the ruling PNC accused of being responsible for the assassination of Rodney who was also prominent in that struggle. Several other issues concerning Rodney stir political interest because of his activities and history.

This, of course, is of great and widespread political interest with further international repercussions. International groupings, including academics such as Jamaican historian/political scholar Horace Campbell took up the matter when South Africa decided to present the Tambo Award to Forbes Burnham for his anti-imperialist support of the struggle against apartheid and African liberation. Burnham was Guyana’s President and leader of the ruling PNC accused of being responsible for the assassination of Rodney who was also prominent in that struggle. Several other issues concerning Rodney stir political interest because of his activities and history.

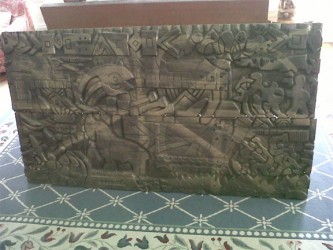

But one event held in Georgetown on June 13, 2013, links Walter Rodney to art. Guyanese sculptor Desmond Ali, whose work has an ongoing connection to resistance, held an exhibition of his art at Moray House which was a dedication to Rodney. This artistic tribute is a reminder that Rodney and his political history have a link to art. More than that, included in his legacy is the very important place his history, his work and his ideology have carved out in West Indian Literature.

Rodney was not known as an artist, but his work has more than a passing reference to artistic literature. First of all, at least two of his publications lay claims to artistic writing. Kofi Badu Out of Africa and Lakshmi Out of India are texts which attempt to make the history appealing to younger readers. They use narratives which somewhat dramatise the historical material, making their author a pretender to the label of creative writer.

Secondly, even if that claim is not convincing, Rodney wrote another text which is much better known than those two and was much more influential than those minor publications. In fact, his Groundings With My Brothers, which came out of his Jamaica experience, became a very influential work with great significance to literature, a deep proletarian text and a humanitarian focus. Rodney was a Marxist as well as an Africanist and this publication helped to popularise the proletarian ideology which found its way into the creative literature in the Caribbean.

The Groundings With My Brothers, subsequently published by New Beacon Books in London, is first associated with the literature through its linguistic roots. It takes its title from a popular Jamaican expression ‘grounding,’ a word used in Dread Talk and popular (as well as populist) slang to mean a down-to-earth sincere reasoning, discourse, or communion with persons. It was also regarded as a working class consciousness, in addition to which, one would ‘ground’ with members of the working class. The adjective ‘grounds’ meant someone who could be trusted, who had proletarian sympathies and shared an understanding with blacks or workers.

So Rodney’s groundings helped to give literary, mainstream and Standard English acceptance to the term and dignify the practice. One of the reasons for his expulsion from Jamaica in 1968 was these very groundings. As a university man, a respected scholar with a reputation of being brilliant, a privileged and influential person with communist, radical and proletarian sympathies, his frequent interaction with working class and ghetto communities made the reactionary government uncomfortable. But this publication, coupled with his deportation, gave strength to literature that reflected or wished to reflect that kind of consciousness. It influenced much writing of and by the Rastafari, but it influenced literature, dub poetry, and at that time (1968-1971) mainstream poetry including Dennis Scott and Mervyn Morris.

The third element is even more pronounced. Many persons would be surprised to learn that Marcus Garvey had a legacy in literature. Not only did he and his United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) have much influence and involvement in the Harlem Renaissance in the USA, Garvey himself wrote poetry and plays. The Rodney factor in West Indian Literature is a bit more pronounced.

This itself is two-fold. Jamaican poet Edward Baugh unintentionally started something that took on proportions more serious than he had in mind, viz, the notion of “the Rodney Poem.” In a poem ‘The Poet Bemused’ (a pun on ‘de-Mused’), he gives ironic and slightly mocking treatment to a poet “de-mused” – his women left him. The woman’s (Muse’s) complaint was that he was shallow and “really had nothing to say /about important topics/like poverty and politics” and to underline that “he never even wrote/ a Rodney poem.” It was a mocking reference to the fashionable practice to write poems about Rodney after his assassination. Poets and would-be poets to show their ‘consciousness’ and political commitment, would write “Rodney poems.”

Mervyn Morris took it up in his usual fashion of deep sensitivity, irony and his own touch of satire, when he wrote ‘My Rodney Poem’ in a serious tribute to Rodney the humanist (not the radical politician). There were many other ‘Rodney poems,’ including a number of other excellent serious ones such as ‘Reggae fi Radni’ by Linton Kwesi Johnson another by Wordsworth McAndrew. Martin Carter’s poem for Rodney includes the memorable lines “I intend to turn a sky of tears for you.” This turning a sky of tears probably alludes to the rain ‒ a whole sky turning out a downpour which magnifies and universalizes the grief expressed by Carter. Morris’ own stress on Rodney’s human (and humanitarian) decency sees him as one who was much more than the political reputation that limits him: “he cared when anybody hurt /not just the wretched of the earth.” Morris’ grief is like Carter’s in Morris’ simple closing line, “he died too soon.”

A book of poems in tribute to Rodney was collected and published in Guyana, but like many such collections moved by emotional rather than literary merit or sound editorship, it is highly flawed. A somewhat better volume was produced in Nigeria by academics and writes in the Positive Review group at the University of Ife (as it was named then).

Yet the most profound and enduring contribution of Rodneyism to West Indian literature developed in the two years following his expulsion from Jamaica on October 16, 1968. The political account and historical analysis of the events have been treated by Jamaican political scientist Rupert Lewis and Guyanese historian Nigel Westmaas. The protest, riots and unrest which started at UWI Mona Campus where Rodney was lecturing and spread to downtown Kingston escalated into cultural shock-waves that moved through the Caribbean and as far as Trinidad.

In the wake of the popular upheavals, were several cultural events which grew into major developments. These tied very easily into other winds already sweeping across the region, like black power, and accelerated others which were only just glimmering such as Marxism, large-scale acceptance in middle class society of Rastafari and African consciousness. Rodney’s The Groundings With My Brothers assumed deeper meaning, popularity and intellectual significance. The actual events were ‘Yard Theatre’ ‒ performances of music, especially drumming, dance and poetry readings at non-conventional venues such as yards, communities and outdoor spaces.

A major feature in and outside of Yard Theatre were poetry readings by leading mainstream poets led by Mervyn Morris, Kamau Brathwaite and Dennis Scott. Although Louise Bennett was not involved, her poems were often read by others at these venues and increased in popularity. These poets gradually intensified the oral qualities in their work, including the increased use of Dread Talk and the Creole language. Simultaneously creole and orality in West Indian poetry deepened and escalated.

Linton Kwesi Johnson’s ‘Reggae Fi Radni’ was not only a tribute to the historian after he was killed, but an ironic acknowledgement of his contribution to the poetry. That is because Johnson was performing in ‘Dub Poetry,’ a form that arose out of the post-1968 Rodney generated cultural waves. The performance, the public reading of poetry in a climate of reggae and dub brought those rhythms into the poetry. At the same time the art of DJ performance and dub were bringing the music closer to poetry reading. These, integrated into the political consciousness and propensity to protest, were the most likely causes of the evolution of dub poetry.

These cultural waves gave rise to several periodical newsletters, small newspapers and magazines both political and literary. In Trinidad there was Moko Jumbie, while the poetry readings at Tapia House fed into the literary journal Tapia, now renamed The Trinidad and Tobago Review. In Jamaica there were Abeng and Savacou, among others. It was in that new literary journal Savacou out of the UWI campus that the first publication of dub poetry was seen. It was not only dub poetry but a new brand of poetic output that reflected the cultural waves. This work was the output of much of what was developing since 1968 – resistance, Rasta, African consciousness, radical politics, orality in the poetry and Creole language use which have greatly influenced West Indian literature and the several directions in which it has developed since 1970.