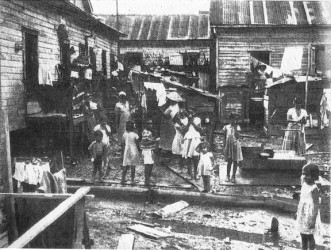

Growing up in a tenement yard, Basil Gibbons would have had direct knowledge of broken families and would have seen how the absence of opportunities denied the young the possibility of developing their potential.

The death of his older brother at an early age and two murders in the yard are events which gave Gibbons a glimpse of the “darker side,” but at 61 what he remembers most about the yard is that despite the negatives, it also had a “harmony, and whenever someone died or somebody was sick everybody come together to help.”

In fact when he moved out of the yard located in Drysdale Street, Charlestown at age seventeen and moved to Festival City, he got what he called a “culture shock.” He recalled that one night there was a wake in the street while four doors down a party was in full swing.

“That would have never happened in Berlin; everyone would have come together and grieved. In Berlin there was a warmness and harmony,” he told the Sunday Stabroek in a recent interview. The yard he lived in was known as Berlin after the German capital during the Second World War, and the area where he lived, which included not only the tenement yard itself but its surroundings as well, was like a war zone, because a truck could not safely pass through without being robbed, among the other crimes which were committed.

But despite all of this Gibbons chooses to remember the warmth of the area and the fact it taught him discipline; his grandmother was a strict disciplinarian, and created in him a hunger to “to achieve things and get out.”

But it is a hunger that many young women and young men who grew up in several such yards around the city did not have, or their circumstances worked against them dooming them to failure from the outset.

According to Barrington Braithwaite, who did not grow up in a tenement yard but had relatives living in one, young men developed the habit of liming on the street corners as there was not much to do at home, and, as he put it, “You could not help see your sister changing…” as the space in the home was so limited. The young men also were not employable by businesses as they could not get adequate training and many of them had dropped out of school.

“So you found limers around town and guys becoming streetwise and gambling… and stuff like that ‒ a different culture evolved.

A culture where appearance became important. You are tied down by how this is constructed so that basically you cannot think of doing stuff for the home… so that is how these guys started looking good on the corner…” he said, and it was there skills in picking pockets and other petty crimes were cultivated.

For Braithwaite back then it was as a means of survival for the youths. He quickly qualified this by saying that not everyone in the yards turned to this way of life, as many of them did well out of school and got out of the situation, but a large number of them remained in a state of abject poverty.

According to Braithwaite the “nigga yard” was basically a small area with crowded “house blocks or cells” of houses where the cooking was done in a little shed outside and the family lived outside.

“These were not big houses, they did not give much scope… some were joined on together, some of them had an independent lil cottage… but these were cultivated for a no end existence for those who were trapped in them,” he said.

He said the yards evolved at the turn of the 1890s because the colonial government had no housing expansion scheme and there were not a large number of jobs available.

“When people talk about the good old days… [they forget] that we live in a time with far more commodities to buy; that is why it seems [more] difficult [now] than we had it then,” he said, adding that there was a credit system in those days but if persons did not have a fixed job even though rents were cheap, they could not be afforded. The cheapest rents were in the yards.

He said that most of the yards were owned by Portuguese, who were used as a “buffer” between the planters and the opportunities that Africans were trying to carve out. He recalled the ‘Jardine yard,’ the ‘Fernandes yard’ and the ‘Camacho yard’ around Georgetown.

It was because of the lack of work, Braithwaite went on, that many people were stuck in Georgetown, as the waterfronts offered the principal jobs available since they could not get much work in the businesses.

Three range houses

In the yard Gibbons grew up in there were three range houses and two cottages. The range houses had rooms and in the one where he lived there were five rooms at the back, two in the middle and four in front. His room was one of those located in the middle, that he shared with his brother, father, uncle and grandmother. His mother and father were separated but she lived in the same yard in another room she shared with five other children, a sister and her sister’s husband.

He recalled that there were three toilets in the yard with one bathroom and a standpipe, which all the occupants of the three range houses shared.

“Looking back now it is difficult to imagine; everyone had to use the standpipe, sometimes fights would develop,” Gibbons reminisced, adding that the culture of the place meant that most of the inhabitants were unemployed, and while the men did labouring jobs at the waterfront, many of the women were employed as ‘bush prostitutes,’ meaning that they would go into the interior to engage in the sex trade for survival. Those persons were looked at as heroes by some in the area, because when they returned from the interior they spent huge amounts of money, and for the young that was all they needed.

He recalled two murders in the yard; one involved a woman killing her abusive husband, while the other concerned a prostitute who was raped and murdered when picking fruit in a churchyard. Her murderer was arrested and sentenced to death following a trial.

But still for Gibbons life was adventurous, and while his grandmother was a disciplinarian her efforts often failed because of the environment. Despite her best efforts, he said, as children they were still regular swimmers in the Demerara River. But they had to wash the dishes when they returned from school and feed the chickens she reared underneath their room that was just a few inches off the ground.

Gibbons still talks with sadness about the death of his brother, who was one year older than him, at the age of 11. His brother had just written Common Entrance and was a rare gem as he got into Queen’s College and was one of the few celebrated children in the area. In fact Gibbons only recalls two other children in his time who did as well; one was a boy who went to Queen’s College while a girl attended Bishops’ High School.

His brother was anxiously awaiting the close of the August holiday to attend his new school but it was not to be. As was their habit they sneaked away to swim in the Demerara River but a watchful boat captain took off his belt and chased the children because the water was dangerous, and it was as they ran to escape the belt lashes that his brother stepped on a nail. Though in pain, the two brothers kept the nail injury a secret because they feared their grandmother’s wrath.

Around 2 am the following morning Gibbons heard his grandmother screaming and when he woke it was to find his brother “unconscious and with his mouth twist up,” but by the time he was rushed to the hospital he was pronounced dead.

The child’s funeral was a huge affair and Gibbons remembers that the church was so filled that persons had to stand on the street. Many of them made the trek to the Le Repentir Cemetery where he was laid to rest.

For Braithwaite growing up in those yards as a child one cultivated certain attitudes of hostility and defiance, “and so you have to recognize that the street fighter and so on evolved out of that sort of environment.”

Braithwaite said he spent a lot of time in the same yard Gibbons grew up in with his relatives, but he realized immediately that he would not want to live in such an environment. He had friends living there with whom he interacted, but he “had the pleasure of leaving and going someplace else and relished that because I had other experiences.”

He recalled in those days the Chronicle had a pull-out page on Sundays of coloured comic strips, and as a young boy he collected them to show his friends that he had the entire series, and while his cousins also collected them it was for a different purpose in mind ‒ to use as wallpaper.

As a young adult Braithwaite had a lot of friends around Drysdale Street and he would go and look at what was called a “chip and paint,” a form of employment at the waterfront to look after the boats when they came in. They would also go to the fish koker where he learned to play dice and got into fights as you had to learn to defend yourself. “The fortunate thing for me is that I had a life before that, that I could have fallen back to, [and] that has enabled me and strengthened me today, but if you had been born in that you had no real options,” he said.

Festival City

According to Braithwaite with independence the late President Forbes Burnham realized that something had to be done as the dialogue in pre-independence was based on jobs and housing and this was across the board, as there was a parallel existence on the estates where Indians lived in what were known as logies.

“This was a colony and Britain saw it as a colony, and not as an aspect of the British Empire or Britain to develop; it was treated as a colony,” he said.

Braithwaite said that Burnham used the hosting of the first Carifesta celebration as an opportunity to build a housing scheme (Festival City) that could give people the opportunity to have new housing.

Gibbons wrote Common Entrance the year after his brother, and was able to attend Central High School. However, he dropped out three years later, after his father died and his uncle also passed away, because he had to help his grandmother and mother. He worked at the Guyana Marketing Corporation as a security guard, but shortly after he moved to Festival City with his mother and other siblings. He remembered attending meetings with his mother at a self-help group that she had joined, and they were eventually selected to occupy one of the houses in Festival City.

“Imagine the pleasure it brought to us, my mother, me and my five siblings in a house with its own bathroom and toilet. It was like a mansion comparably speaking,” Gibbons said.

For him that brought the curtain down on his life as a tenement yard resident, even though he supported his grandmother who remained there. She eventually died and left a piece of land for him on the East Bank which is now owned by one of his five children.