Part 6

Last week’s column indicated that the financing arrangements for the Amaila Falls Hydropower Project (AFHP), envisaged GPL playing a pivotal two-pronged role. On the one hand, one of its several weaknesses (reliance on costly and price volatile imported fossil fuel) provides the most persuasive rationale for the urgent replacement of GPL with an affordable environmentally sustainable domestic electricity source. This rationale is captured in the general priority given to hydroelectricity in all published versions of Guyana’s public investment strategy.

However, as argued here this priority does  not automatically translate into the choice of the AFHP as the most economically efficient project ‒ that is, in the sense it makes the best alternative use of public spending from among all likely investment options for electricity generation. For this, the AFHP should be economically evaluated.

not automatically translate into the choice of the AFHP as the most economically efficient project ‒ that is, in the sense it makes the best alternative use of public spending from among all likely investment options for electricity generation. For this, the AFHP should be economically evaluated.

While the rationale stated above holds, at the same time several other GPL weaknesses raise legitimate red flags about its capacity to fulfil its other financing role efficiently. This is more so, because GPL’s projected cash flow payment to Amaila Falls Hydro (AFH) Inc (under the Power Purchase Agreement (PPA)) is the project’s intended principal source of financing. The rest of this column will assess GPL from this standpoint.

GPL indicators

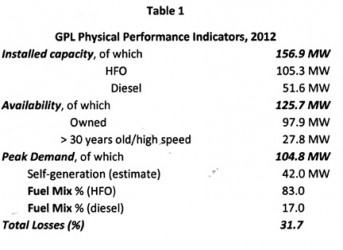

Table 1 below shows some basic GPL electricity indicators at the end of 2012. Its installed capacity is about 157MW and power availability is about 126MW. Its generating capacity mostly utilizes heavy fuel oils HFO (105.3MW) with diesel accounting for the remainder (51.6MW). This HFO/diesel fuel mix is 83:17. GPL’s electricity peak demand is about 105MW. It owns about 80 per cent of its generating capacity, and about one-fifth of this comprises generating sets that are either over 30 years old, or use high speed equipment. Crucially, GPL faces serious electricity losses, both technical and commercial (theft). These account for about 32 per cent of its electricity supply.

GPL profile

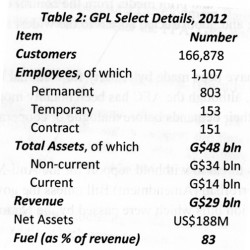

Table 2 below shows the basic profile of GPL. It should be noted that, as a state-owned enterprise, it has an effective monopoly to generate, transmit and sell electricity along the coastal areas.

During 2012, it had serviced about 167 thousand customers, who generated total sales revenue of about $29 billion or US$144 million. The value of GPL’s assets in 2012 was $48 billion, of which non-current assets were $34 billion and current $14 billion. Its net assets are valued at US$188 million. GPL provided employment for just over 1100 persons during 2012.

About three-quarters of these were employed on a permanent basis, and the remainder was evenly divided into temporary workers and contract employees. Most of GPL’s revenue is spent on fuel imports (about 83 per cent).

GPL is a loss-making public corporation that received GoG subsidies of $6.5 billion during 2011-12. It receives (through the GoG) soft loans from Petro Caribe, IDB and China Development Bank. (Note: under current IMF arrangements the GoG’s borrowings require at least a 35 per cent grant element.)

To recall, as previously reported GPL’s principal weaknesses include the following: i) weak revenue administration; ii) considerable losses of electricity supply (technical and commercial); iii) imposition of significant costs on its customers through damaging their equipment via voltage fluctuations, faulty connections and power outages; iv) all this results in those businesses which can afford self-generation of electricity deserting the company or using it as a source of emergency back-up power; v) steady loss of its workforce skills; vi) heavy indebtedness; and vii) weak management (as is consistently asserted publicly by its employees’ main trade union, NAACIE). While this listing is not exhaustive, it is broadly indicative of the wide range of weaknesses confronting the corporation.

The corporation reports it is making strenuous efforts to address these weaknesses, especially as the implementation date for AFHP electricity supply draws near.

Its website notes it is focusing inter alia on 1) electricity loss reduction, largely financed with an IDB loan; 2) fuel switching from diesel to HFO (which is reportedly two-thirds more efficient); 3) improved customer service (reliability and quality); 4) construction of a national electricity grid; 5) improving its generating equipment until AFHP’s power comes on stream; and 6) corporate managerial re-organization and development.

Conclusion

The present weaknesses of GPL are sufficiently grave to require the GoG to provide substantial support and guarantees (including financial) in the project’s framework to guard against its failure/collapse, and by extension the entire project.

On examining private-public partnership power contracts elsewhere, one finds the following types of support/guarantee provisions (as a minimum). One should therefore expect these to apply for safeguarding GPL:

* Keep GPL under government control.

* Maintain GPL’s monopoly on the coast.

* Have GPL’s current debt and claims (Venezuela, China and IDB) subordinated to the project’s senior lenders (IDB and China Development Bank).

* Ensure that when payments fall due under the PPA, GPL will make these on a timely basis.

The following standard formulaic description would therefore, typically express GoG’s assurances:

For the duration of the agreement (between GPL and AFH Inc) the GoG would 1) unconditionally, irrevocably and absolutely support the timely delivery of all payments/services due to AFH Inc under the PPA; 2) enforce the terms (and agreed adjustments) of the PPA when required to do so; and 3) execute the agreement in good faith.

Next week I shall move on to the final topic, focusing on discussing several other remaining troubling considerations (non-financial), which seem to beset this troubled project.