Today marks the 175th anniversary of Emancipation when most of those enslaved in the British colonies ceased to be in bondage.

It was the passing of the Abolition Act in the British Parliament which ushered in eventual emancipation. While it became law on August 29, 1833, it was not designed to come into force until August 1, 1834, and even then, full immediate freedom was not what it intended. The act provided for a period of apprenticeship whereby those who were enslaved would continue to be bound to the plantations and give the planters a substantial quantum of work. Full emancipation was to be accorded the non-field apprentices on August 1, 1838, and for field workers, the date was fixed as August 1, 1840.

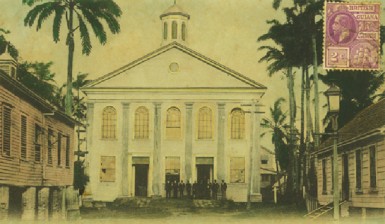

In this country this led to disbelief among many of those enslaved on the Essequibo estates, who refused to accept that complete freedom was to be delayed by four years for some, and six years for most, and it sparked an incident in the Trinity churchyard with which Damon’s name is associated. Damon was hanged outside the Public Buildings in Georgetown for his part in events, despite the fact that there was no violence involved.

In the event, after the passage of four years when freedom for the non-field apprentices approached, some of the island territories decided to free everybody, and not demand the extra two years for what were called the praedials (ie field workers). Eventually the local assemblies in all the West Indian territories followed suit, including the one here. Final emancipation in 1838, therefore, came at the hands of the planter assemblies, and not the British Parliament.

Watershed

August 1st, 1838 marks the great watershed in the history of this country. While it did not mean freedom for the Creoles (as the Africans were called in the 19th century) in anything approaching the modern sense of that term, the new era opened up possibilities which simply had not existed for those who had previously been held in slavery. In the process of creating possibilities for themselves, the Creoles of this country changed the face of the coastland, and redistributed nearly half its population.

The Village Movement in particular (see pages 4B&7B), whereby the Creoles moved off the estates, wrought major demographic and landscape changes, and it was Alan Young, the pioneer writer on the history of local government in this country, who first drew attention to the scale of that movement. “It equalled in size,” he wrote, “the army used by Alexander the Great in Asia Minor and India. It embraced more than four times the number of followers that were with William of Normandy on his invasion of England in 1066.”

He went on to describe how by 1842 the number of emigrants leaving the estates for the villages totalled 16,000. Only six years later that figure had reached 44,000. As a consequence, by 1856, almost half of Guyana’s population could be found in the villages.

Young too pointed to the stunning size of the investment which the Creoles made on the coast. He estimated that in 1848 the purchase of land for the establishment of villages came to over $1million, while the improvements to that land had cost the villagers anything like $500,000. In addition the 10,000 odd village houses scattered up and down the coastal belt represented the investment of yet another $1 million.

The fact that Africans had moved off the estates meant that the planters began to import labour, and in the nineteenth century, British Guiana, as it then was, became a very polyglot, multi-faith society, whose composition was far removed from that during the era which had preceded emancipation.

Education

The vindictiveness of the planters prevented the Creoles from developing economically in any meaningful way and they were stymied in their ventures by a variety of means. However, with the opening of the new church schools they seized whatever educational opportunities they could, while shortly after Emancipation one of them opened a little lending library in Plaisance, for example, and others began to produce newspapers reflecting their viewpoint. The Newspapers Ordinance of 1839 had lifted government censorship, and through the pages of papers like the Creole, the most famous and long-lived of their organs, they talked back to the planters, who for their part patronised the Colonist, in particular.

As the 19th century wore on, the Creoles began to break into the professions, as educators at first, and then as lawyers and finally, doctors. In the twentieth century there is hardly an African village along the coast which cannot boast its scholar or scholars of standing, and that is naturally true of the urban areas as well.

However, while in the 19th century, a Creole lawyer had the freedom in court to harangue a witness Old Bailey style, he could not go into the Georgetown Club, or socialize in a middle class setting with his white legal counterparts. In the civil service, which in due course employed Creoles because of their sound educational background, the clerks were not allowed to rise in the hierarchy; all the senior positions were held by whites, many of them expatriates, whether they were competent or not.

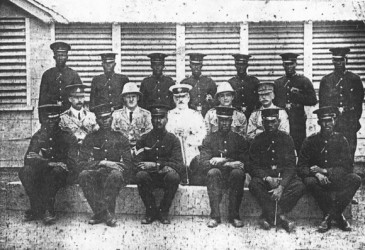

The same was true of organizations like the Police Force, where the officers were white, and the constables, corporals and sergeants were Creole. It was not until after the Second World War that any kind of serious attempt was made to train locals in the expectation that in the long term they would take over administration.