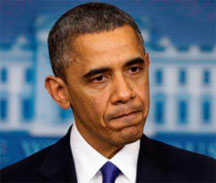

BEIRUT, (Reuters) – President Barack Obama called the apparent gassing of hundreds of Syrian civilians a “big event of grave concern” but stressed yesterday he was in no rush to embroil Americans in a costly new war.

As opponents of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad braved the frontlines around Damascus to smuggle out tissue samples from victims of Wednesday’s mass poisoning, Obama brushed over an interviewer’s reminder that he once called chemical weapons a “red line” that could trigger U.S. action.

A White House spokesman reiterated Obama’s position that he did not expect to have “boots on the ground” in Syria.

Obama’s caution contrasted with calls for action from NATO allies, including France, Britain and Turkey, where leaders saw little doubt Assad’s forces had staged pre-dawn missile strikes that rebels say killed between 500 and well over 1,000 people.

But two years into a civil war that has divided the Middle East along sectarian lines, a split between Western governments and Russia once again illustrated the international deadlock that has thwarted outside efforts to halt the killing.

While the West accused Assad of a cover-up by preventing the U.N. team from visiting the scene, Moscow said the rebels were impeding an investigation.

The United Nations released data showing that a million children were among refugees forced to flee Syria, calling it a “shameful milestone”. And mosque bombings that left at least 42 dead and hundreds wounded in neighbouring Lebanon were a reminder of how Syria’s conflict has spread. But, for now, there seems little prospect of an end to the violence.

According to U.S. and European security sources, U.S. and allied intelligence agencies have made a preliminary assessment that Syrian government forces did use chemical weapons in the attack this week and that the act likely had high-level approval from President Bashar al-Assad’s government.

Obama played down the chances of Assad cooperating with the U.N. experts who might provide conclusive evidence of what happened, if given access soon.

Noting budget constraints, problems of international law and a continuing U.S. casualty toll in Afghanistan, Obama told CNN:

“Sometimes what we’ve seen is that folks will call for immediate action, jumping into stuff that does not turn out well, gets us mired in very difficult situations, can result in us being drawn into very expensive, difficult, costly interventions that actually breed more resentment in the region.

“The United States continues to be the one country that people expect can do more than just simply protect their borders. But that does not mean that we have to get involved with everything immediately,” he said, reflecting long-standing wariness to follow the example of his predecessor, George W. Bush, and his ultimately unpopular ventures in Afghanistan and Iraq.

“We have to think through strategically what’s going to be in our long-term national interests.”

RED LINE?

Asked about his comment – made a year and a day before the toxic fumes hit sleeping residents of rebel-held Damascus suburbs – that chemical weapons would be a ‘red line’ for the United States, he replied: “If the U.S. goes in and attacks another country without a U.N. mandate and without clear evidence that can be presented, then there are questions in terms of whether international law supports it.”

Russia and China have vetoed United Nations Security Council moves against Assad in the past and oppose military action.

Having abstained to allow NATO powers a U.N. mandate to back Libyan rebels against Muammar Gaddafi in 2011, Moscow and Beijing have closed ranks against what they see as a desire by Western states to change other countries’ systems of government.

The U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, despite a failure to secure a specific U.N. mandate for it, led to long wrangling over whether Washington and its allies broke international law.

In June, Washington agreed in response to evidence of small chemical attacks to arm rebel groups, despite misgivings about Islamist radicals in their ranks, some allied with al Qaeda. But rebel leaders say it is too little, leaving only a stalemate.