When the Guyanese nation celebrates Amerindian heritage it is like celebrating Guyana itself. The nation is indivisible from all of its races, but the marks of the Dutch and Amerindian are exceedingly pervasive, with the Amerindian roots particularly deep and its wide branches virtually defining the country.

Heritage will include different meanings for politics and politicians, for historians and archaeologists, but in cultural studies the Amerindian heritage is well nigh unfathomable.

The country derives its identity from its indigenous people. It is in the geography, the landscape, the linguistic vestiges, the folklore, the spirituality, the art, the literature and the creative imagination. It is not surprising that the image and culture of the ‘First People’ would be prominent when a nation seeks identifiable icons and national insignia, but the point being advanced here is that even if there were not those deliberate choices made in designing the national flag or other symbols, the indigenous culture is indivisible from the nation’s identity.

Most prominent in the heritage is the dominant identification with the interior landscape of mysterious rainforests, savannahs, waterfalls and rivers. It is extremely visible in the geography, most obvious in the naming – the ubiquitous Dutch place names are exceeded only by the Amerindian names of villages, rivers, landforms and vast tracts of the country. There might be historical origins and explanations for several of the Dutch names found in so many villages, old forts and plantations, but there is a depth of meaning in innumerable names of Amerindian origin that far exceed any other ethnic source.

Most prominent in the heritage is the dominant identification with the interior landscape of mysterious rainforests, savannahs, waterfalls and rivers. It is extremely visible in the geography, most obvious in the naming – the ubiquitous Dutch place names are exceeded only by the Amerindian names of villages, rivers, landforms and vast tracts of the country. There might be historical origins and explanations for several of the Dutch names found in so many villages, old forts and plantations, but there is a depth of meaning in innumerable names of Amerindian origin that far exceed any other ethnic source.

It is this inherent quality that Mark McWatt alludes to in so many poems of the interior landscape such as ‘A Poem at Baramani.’ In this he discovers that he, or any other writer, does not create poems about such places as Baramani, but that the place, the landscape with its natural features (beauty becomes an inadequate, too ordinary word) are the poem. In ‘A Poem at Baramani’ the poet could not write, suffered the so-called ‘writer’s block,’ until he “found” that the place was the poem. It is the same landscape that Wilson Harris associates deeply with the Amerindian people who inhabit it – although he delves more intensely into the brooding rainforests. Like Pauline Melville, Harris articulates the oneness between the people and the interior places which he emphasizes by using the term “Heartland.” This is the representation of Guyana that he uses to make statements about all the people through the historical periods of the world. He anchors this in the Amerindian people in the Heartland setting which represents Guyana.

The naming of Guyana and its places and landforms, then, is a significant representation of the Amerindian heritage. And it is important not only because of the unimaginable prevalence of these names, but because many of them have spiritual, mythical and historical meaning arising from the Amerindian world picture. It then becomes impossible to separate these from the country itself. There is nowhere you can go, you cannot study a map, without confronting the culture, the beliefs, mythology, languages and cosmic vision of Guyanese Amerindians.

These things are highly visible and obvious, but invade far beneath the superficial into what is not necessarily commonly known. Other parts of the heritage include the little known cultural and scientific resources in Amerindian ethnobotany, ethnomedicine, the uses of plant species. Much of the national patrimony in these and other areas is the product of Amerindian knowledge and scientific practices.

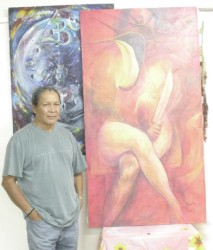

Additionally, many other cultural treasures belong to that heritage, including some that lend fame to the country. Among these are the petroglyphs, and timehri. These are rock carvings, engravings and paintings found in a number of locations in Guyana such as Aishalton and Imbaimadai. These are the source of the name of the main international airport – Cheddi Jagan International Airport, Timehri, and the place where it is located. Again, these are of spiritual and ritualistic significance to the people who created them. They further provide a source of material and inspiration for modern and contemporary Guyanese artists who have used them extensively in paintings, drawings and designs.

The rock drawings themselves are among the ‘Wonders of Guyana,’ but they are an extensive part of contemporary Guyanese art. They have been very seriously explored in paintings by major artists such as Aubrey Williams whose murals based on them enhance the walls of the airport. Other artists of Amerindian extraction like Stephanie Correia often use motifs taken from the rock drawings in various artworks, so they have made extensive contributions to Guyanese art.