The FIDE World Cup is a knockout tournament which is being played in Tromso, Norway, and which concludes on September 3. It began with 128 players representing some of the finest on the planet.

Notable absentees were Anand and Carlsen who are in fact preparing for their world championship clash in November. The winner and runner-up of the World Cup 2013 will qualify for the Candidates Tournament of the next World Championship cycle.

A number of strong players were eliminated leaving Vladimir Kramnik and Dmitri Andreikin to contest the final of the rigorous World Cup. Kramnik annihilated Maxime Vachier-Lagrave and Andreikin disposed of Evgeny Tomashevsky.

Despite playing Black, Kramnik played confidently, quickly and aggressively and immediately took advantage of White’s awkward placement of his pieces. In only twenty moves, White’s position had collapsed.

The biggest chess match in the new millennium ‒ the world chess championship between Viswanathan Anand of India and Magnus Carlsen of Norway begins on November 7 in Chennai, India. During an interview with Ashok Venugopal, Anand was asked whether he felt that after winning five championship titles he had an edge over Carlsen? “Surely, the matches have taught me something. But each match for me is a new challenge. I close the chapter on the previous match and approach this as a new challenge.”

The biggest chess match in the new millennium ‒ the world chess championship between Viswanathan Anand of India and Magnus Carlsen of Norway begins on November 7 in Chennai, India. During an interview with Ashok Venugopal, Anand was asked whether he felt that after winning five championship titles he had an edge over Carlsen? “Surely, the matches have taught me something. But each match for me is a new challenge. I close the chapter on the previous match and approach this as a new challenge.”

How motivated are you to win this one as it is being played at your home venue?

“I think I would be motivated if the match was played on the moon. Being in Chennai, your heart and head keep telling you to win.”

Does it worry you that in recent tournaments you have not been up to your best?

“Surely it does, but I have had worse results before previous matches. I would say that except for Tal [the 2013 Tal Chess Tournament], I actually did play reasonably well. But now it’s only the twelve games and Magnus that matters.”

Your views on Carlsen as a player?

“He is tenacious. Lots of talent and extremely ambitious.”

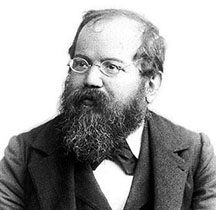

Bobby Fischer named his Ten Greatest Masters in History in the 1960s. We therefore continue with the third such master as named by Fischer.

Wilhelm Steinitz 1836-1900

“Steinitz was the first chess player to be called world champion, a title he claimed after his 1865 match with Anderssen. He is the so-called father of the modern school of chess: before him, the King was considered a weak piece, and players set out to attack the King directly.

Steinitz claimed that the King was well able to take care of itself, and ought not to be attacked until one had some other positional advantage. Pawns ought to be left back, Steintz claimed, since they can only move forward and can’t retreat to protect the same ground again.

“Steinitz was a year older than Morphy. Those two great players met only once in New Orleans, according to reports, and unfortunately they neither played chess nor discussed it.‒ where Morphy was usually content to play a book line in the opening ‒ Steintz was always looking for some completely original line. He was a man of great intellect ‒ an intellect he often used wrongly.

“He understood more about the use of squares than did Morphy and contributed a great deal more to chess theory.

It is also possible that Morphy might have had his own theories but they were never put in writing.

Rather than venture a beautiful combination, Steintz would often win a piece by pinning it. Unlike many other players‒ notably Morphy ‒ Steinitz didn’t mind getting himself into cramped quarters if he thought that his position was essentially sound.”

Steinitz v von Bardeleben

Steinitz v von Bardeleben is one of the most famous games in chess history. The diagrammed position was reached after move 25. Rxh7+ . At that point, von Bardeleben refused to play on. In doing some research on this famous game I came across a quote that was presented by Chess Notes writer Edward Winter.

“But Bardeleben didn’t resign. He stared at 25. Rxh7+, shot a glance at Steinitz and without a word got up from his chair and left the room. He didn’t come back. Tournament officials searched and found Bardeleben pacing angrily. No he wouldn’t return to the board so that outrageous Austrian could mate him.”

So Steinitz had to wait until Black’s time ran out before he could claim the win by default. Not only did Steinitz claim the win, but he demonstrated the final ten move checkmate that he had in store for Bardeleben. Research also brought one Richard Griffith to the fore, the originator of the classic Modern Chess Openings. Here are his comments in relation to the Steinitz win:

“I was a steward at the big international tournament at Hastings in 1895 and was on duty when that wonderful game between Steinitz and Bardeleben was played. Bardeleben seeing he had a lost game left the room, and Steintz sat at the board for fifty minutes before he could claim the game on time. He then showed the spectators how he won in every variation. The applause was difficult to stop.”

Here is the game.

William Steinitz – Curt von Bardeleben

Hastings, 17 August 1895

Giuoco Piano

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 c3 Nf6 5 d4 exd4 6 cxd4 Bb4+ 7 Nc3 d5 8 exd5 Nxd5 9 O-O Be6 10 Bg5 Be7 11 Bxd5 Bxd5 12 Nxd5 Qxd5 13 Bxe7 Nxe7 14 Re1 f6 15 Qe2 Qd7 16 Rac1 c6 17 d5 cxd5 18 Nd4 Kf7 19 Ne6 Rhc8 20 Qg4 g6 21 Ng5+ Ke8 22 Rxe7+ Kf8 23 Rf7+ Kg8 24 Rg7+ Kh8 25 Rxh7+ [Diagram]. Game abandoned. 1-0.