Recalling chess positions which existed previously, is critical for assessing a current position that you are playing. They can help you to make an accurate assessment of an intricate position. Ever since chess was invented in 570 ad (or was it discovered ?) in the north-eastern part of India, remembering similar positions to the one which is being played can prove invaluable for winning a game. Research has indicated that in manuscripts from the early 7th century, a game called ‘Chaturanga’ (which later changed to ‘Shatranj’) is mentioned, a precursor to chess as we know it today. Naturally, we cannot be sure that there were no earlier forms, but the evidence seems to suggest that the game was invented from scratch by a single person in this area of India at around this period of time.

No one knows the name of that ‘single person,’ but we know for certain that it took a brilliant mind to create a game such as chess. Kings, queens, presidents and prime ministers, teachers, investors, businessmen, laymen, etc, continue to be fascinated by the game. It boasts an extraordinary number of possibilities. The original chessboard was mathematically revolutionary. A common theory is that India’s development of the board and chess was likely the consequence of India’s mathematical enlightenment involving the creation of the number zero.

The rules of Shatranj were very similar to those of modern chess. The game was played on a board with 64 dark and light squares, with pieces which we would find quite familiar. It was based on the army formation of the period. There was an infantry (padati, today’s pawns), elephants (hasti , our bishops) the cavalry (ashwa , the knights) , chariots (rat-ha , today’s rooks) and a vizier or counsellor (mantra), which later became a queen. The elephants could only move two squares diagonally, and jump over pieces; the vizier moved one square in any direction. But everything else was much the way it is today.

Wars at the time were decided either by the complete annihilation of the enemy army or by the capture of the enemy king. This was also reflected in Chaturanga. The most important piece was the rajah or king, whose survival or demise decided the victory or the loss of the game. When the Persians took over the game they called this piece the ‘Shah’ and ended a game with the words “Shah Mat,” the king is defeated. This is still retained in the word ‘checkmate,’ which comes from 7th century Persia.

the victory or the loss of the game. When the Persians took over the game they called this piece the ‘Shah’ and ended a game with the words “Shah Mat,” the king is defeated. This is still retained in the word ‘checkmate,’ which comes from 7th century Persia.

The Mansuba

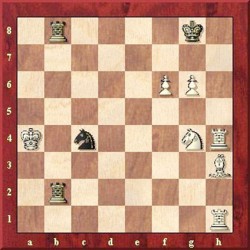

When the Arabs stormed southern Europe in the 9th century, they brought the game of chess with them. They also introduced the first ‘mansuba’ which consisted of composed middle or endgame positions or puzzles with well-defined tasks, eg, white to play and win. There were often stories and legends surrounding the ‘mansubat,’ someone who is held in high esteem. One of the best-known is ‘Dilaram’s mate.’ According to Chess Base Magazine , we can find it in a 15th century chess book by Firdewsi at-Tahihal, who incidentally also authored the longest poem in history (with almost a million verses, which took him 50 years to write). But the position (puzzle) and story originated in the 10th century and probably came from the Arab chess teacher as-Suli (?).

The story is that a chess-addicted prince, Murwardi, had wagered and lost his entire fortune in an intense chess session. In his desperation, he offered his beautiful wife Dilaram as stake, and was losing the game. In the diagrammed position, his wife called out to him: “Oh Prince, sacrifice your … and not your wife.” This her husband duly did and saved her with an extraordinary combination!

a 1958 Soviet postage stamp.

In current news, the Women’s World Championship Match 2013 has begun between World Champion Anna Ushenina of the Ukraine and challenger Hou Yifan of China from September 11- 27 in Taizhou, China.

At the time when the game was played, the Bishop could have jumped over the Knight, if it became necessary. The ‘Alfil’ or Bishop, could move only two squares diagonally, and as I said, had the capacity to jump over other pieces to get to its desired square. In this position for example, the Bishop can move to f5 if necessary. White to play and win!

Yifan won the first game in a Queen’s Indian playing Black.

Mikhail Tchigorin

Added here are Bobby Fischer’s comments in relation to his Ten Greatest Masters in History, the fifth in the list of ten.

“The Russians call Tchigorin, who has been dead for sixty years, the father of the Soviet style of chess; he was, in fact, one of the last of the Romantic School and a good all round player in spite of the fact that almost all of his opening novelties have long been discarded.

“Tchigorin, who was beaten twice by Steinitz, was the finest endgame player of his time, although judging from his notes, he often over-evaluated his position. Steinitz and Tchigorin were rivals ‒ they represented respectively the new and the old schools. After defeating Tchigorin, Steinitz , although 50 years his senior , wrote happily: ‘Youth has triumphed’!

“Tchigorin had a very aggressive style, and was thus a great attacking player. He was always willing to experiment and as a result was often beaten by weaker players. He was easily discouraged, a fact that held him back from even greater heights. He was not really an objective player; at times he would continue playing a bad line even after it had been refuted. In the latter years of his career, after trial and error, he gave up trying to refute Steintz’ lines and began playing them himself.

“Tchigorin was the first great Russian chess player, and still is one of the greatest Russians of all time.”