Marginal role

Cooperatives, though useful, are not a noticeable tool in Guyana’s economic development. Guyana is not the only country where cooperatives, after being a central focus, ended up playing a marginal role in the society. Estonia, Latvia, Poland and Romania are examples of countries in which cooperatives were once a significant part of the economy and currently play a marginal role. The reputation that cooperatives had in these countries reportedly was not a good one, even though their value is well appreciated. While many are slowly returning to the cooperative business model, already rich developed and emerging countries have been taking advantage of it for centuries.

Born out of crisis

Anyone who followed the story of cooperatives over the years would come to realize that cooperatives are quite a phenomenon in the agricultural sector of the major economies of the world. As noted by Thomas Gray (2012) writing in the Rural Cooperatives magazine published by the US Department of Agriculture, “Cooperatives have had a long history of being able to respond to farmers’ needs to gain higher prices and more favorable terms of trade and power in the market place. Farmers marketing together are often able to realize better prices and terms of trade through cooperative organization.” At different times and in different parts of the world, cooperatives have been used to forestall unemployment. They have been used to avoid starvation and they have been used to survive depressions. Cooperatives have made many communities in Europe and North America better and, through strategic alliances, helped to change the economic and social fortunes of their people. The evidence to support the assertion that co-operatives are usually born out of a crisis or usually are the best response to a crisis could be found in a study conducted by the ILO entitled ‘Resilience of The Cooperative Business Model in Times of Crisis.’

The report contains many examples to support the general thesis as reflected by its title. It pointed out that, after the eventual collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Finland experienced a severe recession that led to unemployment reaching upwards of 20 per cent. The unemployed responded by forming about 1,200 workers’ cooperatives. Similarly, in Argentina in 2001, after a financial meltdown and thousands of bankruptcies, workers took over about 200 firms and started running them as cooperatives. Before and even after those events, other acts of turning to cooperatives for help occurred. The ILO report in reference pointed out that during an agricultural depression in 1860 in Germany, Raiffeisen, a social reformer, realized that struggling farmers needed credit to modernize production and gain access to markets for their produce. He designed the rural co-operative bank. It is now an integral part of the German economy.

During the Great Depression in the USA, a cooperative bank was set up to provide farm credit to help save farming communities. The US also decided to embrace agricultural co-operatives in a major way, and created special legislation and institutions to exempt cooperatives from antitrust rules, as well as to protect and support them in their formation and in their operations. In the 1840s in Britain, a period of desperate economic hardship, retail consumer cooperatives were formed in an effort to stave off starvation. The formation of the cooperatives is also credited with preventing Britons from migrating en masse.

Not small

Not small

When people begin to pay attention to the cooperative business model, one of the things that they discover is that the cooperative sector is not small. The World Council of Credit Unions reported that it has a membership of 49,000 credit unions from 96 countries with a total of 177 million individual members. The International Raiffeisen Union, a German inspired institution, points out that 900,000 cooperatives with around 500 million members in over 100 countries are working according to the cooperative banking principles. To give further emphasis to this point, in Europe, there are 4,200 local co-operative banks and 60,000 branches that account for 20 per cent of the financial market share. The banks serve 45 million members and over 159 million customers. Taiwan Cooperative Bank is the second largest bank in Taiwan and in Canada, Groupe Desjardins controls a 39 per cent market share in residential mortgages, a 47 per cent market share in farm credit and 44 per cent in personal savings in the Province of Quebec. Given the scale of their operations, it is not surprising that the International Cooperative Alliance reported that the 300 largest cooperatives in the world have a combined output that is as large as that of Canada’s. Expressed in numbers, the 300 cooperatives are responsible for US$1.7 trillion of economic activity.

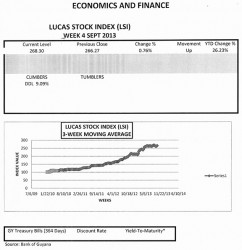

The Lucas Stock Index (LSI) rose by 0.76 percent in exceedingly light trading during the fourth week of September 2013. Trading involved one company in the LSI with a total of 1,666 shares in the index changing hands this week. As a result, there was one Climber and no Tumblers. The Climber was Demerara Distillers Limited (DDL) which rose 9.09 percent on the sale of the 1,666 shares.

Largest banks

A second thing that people discover is that some of the largest banks in the world are cooperatives. For example, Rabobank is the largest agricultural bank in the world. It was founded over 115 years ago by Dutch citizens who had no access to bank financing. Rabobank continues to enjoy member support from as much as 50 per cent of Dutch citizens. Another example is the Norinchukin Bank of Japan. The Norinchukin Bank is the third largest bank in Japan and is identified as the 31st largest bank in the world. It has 16 subsidiaries involved in a variety of areas including, training, research, fund management, building management, asset management, systems development, credit cards and mortgages. The largest shareholders of the Norinchukin Bank are the Japan Fisheries Cooperative and the Japan Agricultural Co-operative Society to which 90 per cent of Japanese farmers belong.

Beyond national boundaries

Cooperatives are investing beyond national boundaries even though they might modify the business model to carry out their work in foreign countries. Evidence of foreign investment by cooperatives could be seen in the business profile of CHS, Inc, the largest cooperative society in the USA. CHS is often described as a mixed type cooperative because it derives between 25 to 75 per cent of its income from farm supply sales and marketing of products of other cooperatives. Based in St Paul, Minnesota, CHS does business in 65 countries and has offices in 24 of them in which a total of 1,000 persons work. Its first overseas office was set up in neighbouring Brazil 10 years ago. Ever since adding the overseas strategy to its cooperative business model, it appears that CHS has been opening an average of two to three offices per year. A Rabobank could be found in at least 60 countries around the world and is present on every continent. The Norinchukin Bank also has a global footprint with offices in New York, London, Singapore, Hong Kong and Beijing.

The rich and powerful

From the foregoing comments, one thing that is obvious is that the rich and powerful countries have used and are using cooperatives the most to their advantage. In the USA, the country with the largest economy and regarded as the most market oriented, 86 per cent of all dairy products are produced by cooperatives and 94 per cent of all such products are marketed through cooperatives. And, this is something that all Guyanese might want to think about with respect to Amaila Falls or any future hydropower project and electricity supply in Guyana. Today, half of the total electric lines used to distribute electricity across the entire USA are owned by cooperatives. Further, the most common form of apartment ownership in New York is the cooperative. In fact, the USA is replete with stories about workers converting investor-owned businesses into cooperatives or about cooperatives buying out investor-owned businesses that ran into trouble since the financial crisis of 2008.

In Singapore, a country with one of the highest per capita incomes in the world, nearly two-thirds of all supermarket trade is done through cooperatives. And in Kuwait, a country of no ordinary means, 75 per cent of all retail trade is done through cooperatives. The average market share of the agricultural cooperatives in Europe is 40 per cent, though it is much higher in some member countries where it reaches as much as 70 per cent. In a European Union commissioned report entitled ‘Strategies for Cooperatives’, it is reported that the cooperative financial sector in Europe provides as much as 30 per cent of the financial needs of small and medium sized enterprises that are not cooperatives. The report also gives an indication of the reach of European cooperatives. There are as many as 46 transnational cooperatives in Europe, meaning enterprises with members in more than one EU member state.

Survival rates

Once formed, cooperatives tend to outlast most investor-owned businesses. A Canadian study revealed that cooperatives have a 60 per cent survival rate compared to 40 per cent for investor-owned businesses during the first five years of existence. The survival rate improves to twice that of investor-owned businesses when measured over a 10-year period. These survival rates are no fluke. They are partly the result of the nature of the cooperative business model and partly the result of good management. The two critical ingredients in a cooperative business model are participation and cooperative education. Even as we speak, many innovations are taking place in the cooperative movement as a result of the intense investment in cooperative education in Europe and North America. At the centre of all the changes is the self-development of individuals that is built on a platform of community involvement and community values.

Dire financial circumstances

The lessons about the effective use of cooperatives in the rich and powerful nations could be valuable to Guyana. The formation of cooperatives is often seen as the best response to a crisis and there is one in Guyana as could be ascertained from the budget presentation of 2013. Therein, it was stated that about 59,000 or 24 per cent of active employees qualified for exemption from income tax. Assuming that all affected employees earned the maximum exemption of $600,000 per year, then nearly a quarter of the active labour force shared in less than seven per cent of the total income generated by the economy last year. Assuming further that each worker is responsible for a household of two persons, as many as 118,000 Guyanese or 15 per cent of the population could most likely be in very dire financial circumstances.

Elwood

Further, like farmers elsewhere, Guyanese farmers are experiencing the cost-price squeeze with the result that the ‘non-traditional’ agricultural sector is in crisis. While it might not look the same as before, poverty exists and its effects are deepening. Something must be done to arrest this descent into desperation. To do so, we must offer people hope and one of the best ways of accomplishing such a goal is to bring people to the altar of cooperation. Examples of hope are all around us. But, my mind ran on the town of Elwood in the State of Nebraska in the USA. In January last year, the only grocery store that it had, closed its doors. Without a grocery store, Elwood faced the prospect, like many of our villages, of a diminished quality of life, stagnating or even dying since it would have been unable to attract new residents. As noted earlier, cooperatives have proven time and again that they are the best response to a crisis. And that is what Elwood did. It formed a cooperative and reopened its grocery store, thereby saving its community. Guyana must have the willingness to do like the community of Elwood to succeed and it must do so quickly.