Mark Plew has worked in Guyana for the past twenty-five years. He serves as a member of the Science Advisory Board, Walter Roth Museum of Anthropology and as Associate Editor of the museum’s journal Archaeology and Anthropology. He has had a long affiliation with the University of Guyana’s Amerindian Research Unit and is Director of the Denis Williams Summer Archaeological Field School.

By Mark G Plew

Professor, Department of Anthropology

Boise State University

Recent years have seen our knowledge of Amerindian prehistory increase significantly. Based upon the work of Smithsonian archaeologists Evans and Meggers in the early 1950s and the extensive body of work by Guyanese archaeologist Denis Williams we have a basic outline of the chronology and material culture of past Amerindian cultures. Evans and Meggers and Williams provide broad synthesis of the prehistory—a synthesis that goes beyond the specific accounts offered by 19th and early 20th century writers like im Thurn, Roth and others.

Beginning in 1997 I began a series of investigations designed to build upon earlier studies and expand our understanding of the diversity of Guyana prehistory. In this context I have worked with a number of colleagues and students. Some of this work has been conducted as part of the Denis Williams summer

archaeological field school programme that trains local students in basic methods of data recovery. Beginning as a joint Walter Roth Museum of Anthropology and University of Guyana programme more than 40 students have participated in projects reported here. These efforts have been facilitated by a number of individuals that include Jennifer Wishart—long-time colleague of the late Dr Williams, Gerard Perreira and Louisa Daggers—all formerly of the Walter Roth Museum of Anthropology. Strong support has been provided by Dr Frank Anthony and the Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sport.

Paleoindian period

Guyana prehistory is divided into three major periods during which prehistoric peoples expanded into different regions of the country and practised varied subsistence strategies. The first period which may date as early as 12,000 years ago is often referred to as the Paleoindian period during which time late Pleistocene (Ice-age) peoples engaged in the hunting of large animals such as the giant ground sloth. It is likely that during this period peoples passed through southern-eastern Guyana into northeastern Brazil—a time during which the Rupununi and Sipalwini savannahs of Suriname would have served as corridors for migration. Notably, however, no definite Paleoindian sites document a pattern of big game hunting. More likely, late Paleoindians in the savannahs of southern Guyana were generalized foraging groups that used multiple resources and moved about with regularity. This type of settlement/subsistence is now widely accepted as the strategy most common among Late Pleistocene peoples. Though little is known of these peoples, they produced well-crafted, triangular-bladed projectiles sometimes made from quartz. Such points have been found near the Ireng and Cuyuni Rivers and have been more recently reported from Mariwau in the south Rupununi.

Archaic period 7-800 bp – 3500 bp

Beginning around 7,000 years ago modern conditions emerge giving rise to regional patterns. What is known as the Archaic period begins about 7-8000 years ago and persists until about 3500 years ago when horticulture becomes the common pattern of subsistence. The Archaic is widely thought of as a period when multiple resources were used and during which there was considerable regional variation.

In the northwest, along the coast and around the swamps of the Pomeroon, numerous shell middens (accumulations of refuse) reflect the extensive use of a variety of shellfish that include snails, mussels, oysters, crabs and conchs as well as birds, fishes and mammals. By analogy it is presumed that a range of plants including palm were utilized by local groups. These periods are correlated ‒ as is the Paleoindian Period ‒ with episodes of increasing and diminishing sea levels which alternately left significant portions of the coast inundated.

These environments changed over time resulting in the presence and absence of different invertebrate species adapted to different water conditions. The oldest of the shell middens date to around 7000 years ago—the oldest the site of

Piraka on the Pomeroon dating to about 7300 years ago. Recent investigations of the newly discovered Wyva Creek midden located on a tributary of the Waini River has produced the remains of porpoise and giant rockfish and large freshwater fish suggesting as do recent excavations at Siriki shell mound that resources other than shellfish were commonly utilized by Archaic peoples.

Mounds served as living areas and as locations for burial. Recent investigations at Sirki shell midden identify what appear to be as many as four separate occupations of the mound. Siriki, the largest of the shell middens also produced the highly fragmented remains of nine individuals including adults and sub-adults. Most appear to have been male between the ages of 20 and 40. Radiographic imaging of the remains showed no Harris Lines—these are indicators of arrests in development marking periods when resources were limited.

Of further note are radiocarbon dates that date the early occupations of the mound to around 4700 bp (before present) and a very recent date of 270 bp. The latter date suggests that mounds may have been used as living platforms and perhaps for burials in relatively recent prehistory.

We have recently developed a typology of shell mounds. These include conical mounds like Pirika and Waramuri, accumulations of shell refuse on hillocks and or other prominences like Barabina and Kabakaburi and flat-topped ‘loaf-shaped’ mounds like Wyva Creek and Siriki.

Alaka Phase (Archaic)

The Archaic in the northwest is referred to as the Alaka Phase which dates between 1950 and 1450 bp. The mounds dating to this time period range up to 80 x 30 metres and are between one and fifteen metres in height. The toolkit associated with the earliest populations include simple percussion made choppers, hammerstones and picks produced from andesite, quartz and schist. Archaeological features of the early Archaic Alaka Phase include fire-cracked rock, concentrations of lithic (stone) debris, hearths, storage pits, postmolds from structures and burials. Though generally considered a pre-ceramic phase (ie before pottery started to be made) Evans and Meggers suggested that the later part of the Alaka Phase was an “incipient ceramic” phase associated with a few crudely made shell-tempered sherds of the type Wanaina Plain—and an indicator of early horticultural activity. Recent investigations at Kabakaburi corroborate Evans and Meggers’ observations regarding the presence of some pottery in very late Alaka Phase contexts and raises a question regarding traditional cultural historical assumptions regarding the presence of pottery as an indicator of horticultural activity.

Abary Phase (Archaic)

The archaeology of the northeastern Guyana while not well known is characterized by the Abary Phase defined by Evans and Meggers and by the Hertenrits culture defined by Boomert in Suriname. The Abary Phase is comprised of sites between the Abary and Berbice Rivers and is a forest pattern utilizing both interior and perhaps coastal resources. The settlement pattern includes seasonal use of primary and secondary waterways allowing for the utilization of seasonally varied landscapes and resources. The pottery types, Tiger Island, Taurakuli and Abary Plain are distinguished by sherd and sand temper. The second pattern includes what Boomert has defined as Hertenrits culture. While settlement, subsistence and material culture is similar to the Abary, the presence of habitation mounds and raised fields is notable.

Typical of the Hertenrits pattern is the Joanna Mound on the Canje River. Measuring 90 metres in diameter and rising some 2. 5 metres above ground level the mound is encircled by a moat-like feature. Additionally interesting are raised field features found in the vicinity of Fort Nassau on the Berbice River. The presence of raised field mounds suggest significant horticultural activity within the area. The recent ‘Berbice Project’ conducted by Neil Whitehead, Michael Heckenberger and George Simon document terra preta or Amazonia Dark Earth sites (habitation sites) and agricultural earthworks dating to c 5000 years ago—amongst the oldest in the Amazonian region.

In the central Guyana rainforest, recent explorations into the archaeology of Iwokrama have documented Archaic and Horticultural occupations that include habitation sites, manufacturing stations, groundstone basins and pollisoirs (grinding surfaces) and petroglyphs. Though no evidence of Paleo-indians has been identified, their presence in surrounding areas is known. It seems likely that Paleoindians utilizing the northern Rupununi would have intruded into the Iwokrama forest.

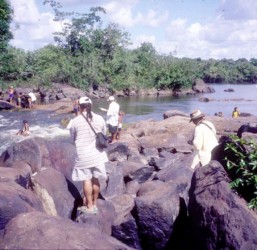

The Archaic Period, which dates between 7,000 and 3,500 years ago, suggests a pattern of broad spectrum foraging. On the Essequibo, Archaic period sites include petroglyphs, sharpening grooves and a chipping station. Petroglyphs belong to the Enumerative and Fish Trap Petroglyph Tradition described by Williams and occur at many sites including Kurupukari Falls and Cuneiform Rock-1. On the Siparuni River, Archaic petroglyphs and large numbers of artificial stone depressions and sharpening grooves are located at Electric Eel Rock, and Tapir Rock.

On the Burro Burro River, Archaic petroglyphs, artificial depressions and an Archaic chipping station have been found along artificial depressions and sharpening grooves and

many thousands of pieces of quartz debitage (waste produced during the making of stone tools) as well as choppers at Inscription Rock. The Archaic settlement of Iwokrama indicates the use of a variety of locations within the forest and along the rivers and a range of site types suggesting that Archaic peoples were both processing local products and manufacturing stone tools.

The settlement pattern of the Archaic is one in which sites were situated along major river courses and near falls, and rock outcrops. Local foraging populations utilized the fisheries and other forest resources using stone tools produced from locally acquired materials. The recent discovery of aboriginal sites along tertiary drainages at some distance from major rivers may indicate a more extended forest occupation.

The Horticultural Period in Iwokrama dates between 3,500 bp and the Historic period. Excavations at sites on the Essequibo River, particularly those from Errol’s Landing document a wide range of ceramic bowl and globular vessels. Though the majority of ceramics are undecorated (+90%), decorated wares include the use of red-on-white painting, incisions, punctation (noding), brushing, stamping, modelling and fingernail incisions. The recovery of early Polychrome Horizon Style ceramics may prove significant in understanding the origins and distribution of this ware in Guyana and the region. Recent discoveries near Toka Village indicate that similar wares were being produced locally or traded between the Iwokrama area and the north Rupununi. The settlement pattern in Iwokrama is one in which horticultural villages/encampments were located on larger river terraces and near falls and estuaries and suggests a continued emphasis upon fishing during the horticultural period. Recent excavations at Errol’s Landing note the presence of Taruma Phase materials.

To the south, the archaeology of the Rupununi Savannahs suggests as noted, a possible early Paleoindian presence as evidenced by paleo-type points found near the Ireng River and recently from the vicinity of Mariwau in the south savannahs. The Archaic pattern is assumed to date as early as 7000 bp and is characterized by a range of chipped and portable groundstone artifacts and features that include grinding surface/depressions and sharpening grooves (pollisoirs) that are found along river and stream beds. A typology of these features has been recently established and that identifies shallow circular to oval basins, broad and elongated grooves and shallow trough like features set end-to-end. Geometric rock alignments, stone piles (cairns), and circles are common. The Archaic is also characterized by extensive evidence of petroglyphic rock art that include sites at Aishalton and Makatau Mountain where 30 petroglyph sites include bimorphic and geometric motifs with elements described by Williams as being inscribed using a broad line and deep groove technique which often combined dots and furrows placing them in settings with bimorphic and geometric motifs. Recent surveys in the south continue to identify rock art sites.

Rupununi Phase pottery

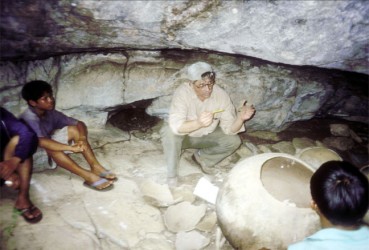

The Horticultural Period in the Rupununi is associated with the first presence of pottery and is associated with the Rupununi Phase (Evans and Meggers 1960). The phase thought to be associated with the historic Makushi and Wapishana is believed to date from the end of the 18th century and often contains 18th and 19th century European trade goods. A recent radiocarbon date from residues from the interior surface of a vessel collected by Evans and Meggers appears to confirm the recent dating of the phase. Two pottery types, Rupununi Plain and Kanuku Plain constitute the majority of the ceramic inventory. Forms include deep bowls with steep walls, globular bowls and jars with rounded walls and incurving and rounded lips and carinated vessels forming round to sloping shoulders. A few sherds include decoration in the form of appliqué, punctuates, white paint and white and red slips. Ceramic artifacts include pottery rests, disks and anthropomorphic figurines. Chipped and groundstone artifacts include anvils, choppers, grooved axes, hoes, manos, metates, hammerstones and stone bowl fragments. Near Moco-Moco the first known cairn burial (burial within stacked stones) was discovered containing the remains of an adult male dating to the Rupununi phase. Other notable burial locations have been recently documented at Shiriri Mountain and in the vicinity of Shulinab where sealed and open burial urns have been found in rockshelters in association with pictographic (painted) rock art. These sites represent the first documented pictographic sites in the region. The motifs are very similar to those described by Reichle-Dolmotoff for the Tukano whose shamans produced distinctive rock art patterns under hallucinogenic influence. The Shiriri Mountain site also provides the first evidence of cremation as a form of disposal of the dead.

The settlement pattern includes habitation sites (open villages), manufacturing stations, fishing sites, ceremonial sites (rock alignments), cemetery sites and rock art locations. Most recently, surveys at Karanambu have identified large lithic reduction stations that have heretofore not been recorded in the Rupununi. These sites cover many square metres and are characterized by extensive cores and lithic flakes associated with the manufacture of stone tools. Recent investigations suggest a broader range of activities and site types within the area as evidenced by the elaborate cemeteries at Shiriri Mountain and hilltop villages near Toka. The diversity of Rupununi settlement reflects the varied nature of the savannah environment in which Amerindians utilized open terrain along streams and rivers for habitation, adjacent bush islands for farming or gardening and higher elevations within the mountains for ritual practice and for cemeteries.

Recent investigations of the prehistory of Amerindian cultures continues to document a broad range of variation in human land use that spans several thousands of years and is characterized by a variety of settlement-subsistence patterns that include the rainforest and the mixed resources of the savannahs. Within the range of environmental setting we find much evidence of sub-regional strategies as exemplified by the shell middens of the northwest and the extensive agricultural development in the Berbice region. The material cultures of the past are equally diverse and demonstrate considerable local innovation. Future investigations must seek to more widely identify the distribution and range of site types within major physiographic and environmental areas and conduct excavations which permit the development of more detailed chronologies. This work must also collect paleo-environmental data relating to past environmental change as the basis for assessing long-term variations in procurement strategies. Continued exploration of the Amerindian past will position Guyana to contribute significantly to a better understanding of the archaeology of the Guianas and adjacent areas.