There are nine nations of Amerindians living in this country today, although they do not represent the sum total of those who have always been here. They are the Waraus, Arawaks and Caribs, who for the most part are found in coastal areas and the coastal hinterland; the Macushis and Wapishanas, located in the North and South Rupununi Savannahs respectively; the Akawaios in the Mazaruni; the Patamonas in the Pakaraimas; the Arekunas on the border with Venezuela; and the Wai-Wais in the far south of the country.

It is customary to classify Amerindian nations according to the languages they speak. In fact, some of the discoveries concerning the very early movements of Amerindian peoples have come from linguists involved in research into the spread of languages.

Three linguistic groups are represented in this country. The first of these is Warauan, which many linguists thought to be entirely independent with no relatives on the South American continent, although not all are convinced of this. The second is Arawakan, taking its name from the Arawaks (Lokono), but which in this country also includes the Wapishanas. Having said that, an Arawak speaker can no more understand a Wapishana than could an English speaker a German; the languages are related, but have evolved apart over the centuries.

All other nations in this country speak various tongues associated with the Cariban family of languages which takes its name from the Caribs – or True Caribs, as they are sometimes called.

Spaniards and Arawaks

Not all of the nations we know today were necessarily here when the Europeans first showed their faces along this shoreline, although some of them certainly were. It was the Spaniards who first started appearing off the coast of what is now Guyana, very early in the 16th century. At this point, the Guyana coast seems to have been very much the province of the Arawaks, with the exception of the Waini River and parts of the Barima which were in the hands of the Caribs.

Spanish visits at this stage were very sporadic, although that did not mean that some of our Arawaks were not in contact with them.

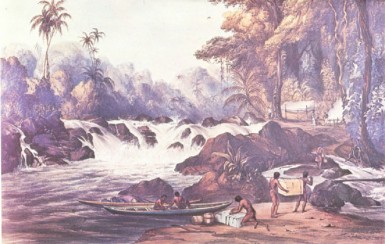

The Spaniards had occupied the islands of Margarita, Cubagua and Coche off the coast of Venezuela, where they treated the local Amerindian inhabitants appallingly. Spanish interest in these barren isles centred on their pearl fisheries, but while they supplied wealth for the conquistadors, nothing much grew on them, and food supplies largely had to be imported. Some Arawaks may have made contact with the Spaniards there as early as 1510, and eventually, the European inhabitants of Cubagua became dependent on the Arawaks for their basic supplies. Members of the nation from Trinidad and the Orinoco as well as Essequibo would travel in their piragas to the Pearl Islands, as they were called, with foodstuffs and various other items to barter.

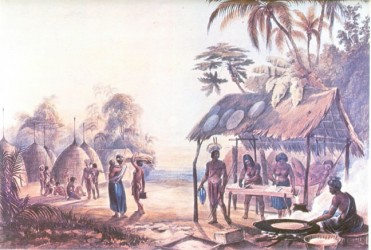

There were hitches in the relationship during the 16th century, but for a large part of it trade between the two sides proceeded tolerably smoothly. There are references in the Spanish sources to the Arawaks on one occasion rescuing the islands from near starvation by bringing in 600 loads of cassava bread and other foodstuffs, while at a later stage it was said that in times of drought the Arawaks could produce 2,000 loads of cassava bread at a month’s notice.

And what did the nation get in return? Most important, for a time they became the effective regional distribution agents for iron goods such as knives and axes, which were highly prized in stone-age cultures. In addition, during a period when the Spaniards were facing a labour shortage consequent on their terrible abuse of the indigenous population, the Arawaks were guaranteed immunity from enslavement, further evidence of the dependence of the conquistadors on them for their provisions.

Towards the end of the 16th century there was a hiatus in this relationship caused by the appearance of a different group of Spaniards in the region, this time in the Orinoco region of modern Venezuela. These had a very tense relationship with their compatriots in Margarita and Cubagua, who thought the newcomers were trespassing in their sphere. These new conquistadors were led by Antonio de Berrío, who was eventually to be captured by Walter Ralegh, and who fed the Englishman a fanciful story of El Dorado which Ralegh believed. It is owing to this encounter that El Dorado and the fabled city of Manoa on Lake Parime came to be sited by cartographers in our Rupununi for almost two centuries.

In contrast to the Spanish-Arawak arrangements in the Pearl Islands, Berrío treated all the nations he encountered along the littoral to the east of the Orinoco with great brutality, including the Arawaks, and despite one or two attempts by the Pearl Islanders to maintain contact with the latter, that trading link effectively came to an end.

By this time, of course, other European nations like the English, Dutch and French were intruding into the New World, and the fact that these tended to be hostile to the Spaniards but were equipped with the same weapons emboldened the indigenous nations to start confronting the latter. Ralegh in particular regarded all human beings everywhere as political animals, and he treated the nations in this part of the world as if they were engaged in the same kind of intrigue that he was familiar with from the Elizabethan court. He made extravagant promises to them that in a grand alliance with the English, they would drive out the Spaniards from the region, and some of them, at least, believed him. More typical perhaps was the view of one leader who was recorded by one of Ralegh’s captains as observing ruefully that in order to get rid of the Spaniards they would probably have to put up with other Europeans in their land.

In the early 17th century the Arawaks were in effective revolt against the Spanish, although there was no unified action as such. For their part, the Essequibo members of the nation attacked some Orinoco Spaniards who came into the river to trade in 1619, and the Spanish governor of Santo Thomé in Orinoco was so angry about it that he sent a military force to punish them. He made the mistake, however, of returning a second time, but on this occasion the English were in the river trading with the Amerindians and they captured the Spanish commander, causing all his compatriots to flee. It was the last time the Spaniards were to enter the Essequibo.

The Dutch

The European nation which eventually established itself here was the Dutch. There is a brief reference to the Spaniards trying to set up a fort in the Barima in 1530, but that was Carib country, and the Caribs wasted no time in eliminating it. The Spaniards did not come back.

Exactly when the Dutch founded the colony of Essequibo is by no means certain, but it may have been in 1616, and if not, they were certainly here by the early 1620s. More is known about the establishment of the colony of Berbice, which dates back to 1627. What can be said is that the Dutch did not come alone; they brought a small number of Africans with them – six in the case of Berbice.

From the beginning, they seemed to have maintained good relations with the Amerindians, and the reason is not far too seek: they were heavily outnumbered for one thing, and from a 1629 account of a ship’s captain who visited Berbice, they were entirely dependent on them for their food supplies. As the Dutch entrenched themselves, they also demonstrated that unlike the Spaniards, they had no interest in converting the indigenous population or interfering with their lifestyle.

In addition to this, in the earlier part of the 17th century the Dutch were prepared to fight the Spaniards, and in conjunction with a variety of Amerindian nations, in 1637 they razed Santo Thomé – the Spaniards’ only little settlement in the lower Orinoco – to the ground.

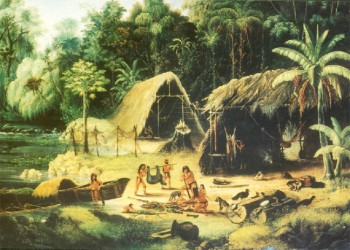

But the cultural influences were not all one way, with only the habits of the Amazonian nations being changed by the adaptations to European ironware and the inevitable beads; the Dutch too adapted their ways to those of the indigenous people, eating their food – particularly cassava bread – drinking their alcoholic beverages, travelling in their canoes, sleeping in their hammocks, and copying some of their bush practices.

What the Dutch did do was introduce a certain stability into local inter-tribal relations, which may have encouraged the Waraus to move out of the Orinoco delta along the Guyana littoral. (According to their own traditions recorded by WH Brett in the 19th century, they had once lived here before, but had been driven back into the delta by the Caribs.) In addition, the ancient hostility between the Arawaks and the Caribs came to an end.

The Caribs

The most numerous nation in Essequibo, at least – although not in Berbice where the Arawaks were probably the dominant group – was the Caribs, who played an active role in the early history of the colony. Unlike the Arawaks who had had a trading relationship with the European inhabitants of the Pearl Islands in the 16th century, Carib relations with the Spaniards were hostile from the beginning, and their first clash occurred as early as 1530.

By the 17th century, a hatred of the Spaniards had become deeply embedded in the Carib national psyche and they attacked Spanish mission settlements without any incitement from the Dutch because they saw them (correctly) as the instruments of Spanish penetration in the region. Their hostility arose from the fact that the Spaniards first attempted to enslave them wherever they encountered them, and then later rounded them up into fortified missions.

The Caribs were eventually to acquire firearms, and their proficiency with these as well as their familiarity with European battle tactics was attested to by both the Dutch and the Spaniards. In the larger Carib strategy of keeping the Spaniards at bay, the Dutch had an important role. They were a source of firearms and ammunition, they were a source of trade goods and they provided a safe haven in the rear when the Caribs had to retreat.

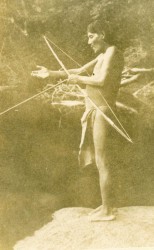

The Caribs lost the war with the Spaniards to the north of the Orinoco where they were forced into missions, but the great swathe of Caribs to the south of that river put up much fiercer resistance. But before the Spaniards began to get a grip on the Orinoco after 1750, the Essequibo Caribs and their Orinoco compatriots who had now replaced the Arawaks as the distribution agents for European goods among the nations of the region, fought to maintain their trade monopoly with the Dutch. They embarked on a long trade war with the Caberre of the Middle Orinoco, and at a later stage also stopped the Manaos of the Rio Negro in Brazil from making contact with the Dutch for the purposes of trade.

The Caribs were subservient to no one and their Uils or chiefs insisted on sitting down when they went to talk to the Dutch governors of Essequibo. They addressed the latter as “mate” or “brother” and refused to allow the Dutch overall command of their warriors when they went on joint expeditions with them.

That Guyana is the shape it is today owes not a little to the Caribs because of their alliance with the Dutch and their determination to keep the Spaniards out of the Dutch sphere. However, the Caribs also had a less savoury reputation as the slave traders of the region, since from the end of the 17th century onwards their main item for exchange was members of other tribes. There was not much of a market for Amerindian slaves in what is now our Guyana ‒ although there were far more of them in Essequibo than in Berbice ‒ so most of them were sold in Suriname. It is from the Dutch slave-traders, in fact, that the Caribs usually acquired their firearms, although in special circumstances like revolt on the plantations the Dutch authorities would issue them with guns.

There were four protected nations (called ‘Free Nations’) in Essequibo, Berbice and later, Demerara, namely, the Caribs themselves, the Arawaks, the Waraus and the Akawaios. No member of these groups could be enslaved, although the Caribs had longstanding hostile relations with the Akawaios, and on occasion sold any captured members of this nation in Suriname, where they did not enjoy protected status.

In practice, however, more groups than these had immunity from enslavement if they lived within the Dutch sphere; it was the nations from outside it which were most at risk from Carib raids. Amerindian slaves in Guyana were mostly women and children, the women being used in household tasks and in the preparation of cassava bread. The men would be employed to clear bush prior to planting the fields and in hunting and fishing for the plantation. They were subject to the same draconian penalties as their African counterparts, although that did not prevent fairly frequent attempts at escape, particularly in Essequibo.

The Amerindians are particularly associated with the recapture of African slaves in the public mind, although this is only true towards the end of the Dutch period, when they ceased to be important to the authorities as a source of trade items such as annatto (which was exported to the Netherlands to colour Dutch cheese), or food supplies, and were only wanted as custodians of the plantation. In addition, it must be pointed out that when the Caribs went out to recapture runaways, they made no distinction between Amerindian and African runaways.

Amerindian slavery was finally abolished by the Dutch in 1793, forty years before the Emancipation Act liberated the African enslaved.

Revolt

Immunity from enslavement did not mean that the relationship between the Dutch and the free nations was always a smooth one. There were constant complaints in Berbice and Essequibo about the maltreatment of members of the four nations by the planters in particular, a problem the authorities never succeeded in stamping out.

Then there was the case of the Arawak uprising which occurred in Berbice in 1687 and where the Amerindians were joined by some of the Africans on the plantations. Little is known about its origins, although it may have had to do with exploitation and maltreatment. It is thought that at least some of the Arawaks involved decamped to Trinidad after it was put down, presumably to evade reprisals from the authorities.

The last free tribe revolt occurred in Essequibo and Demerara in 1755. It was fairly small scale because on this occasion the Akawaios – the nation involved – were very selective about their targets, attacking only those plantations where they felt they had been cheated or badly treated. No reprisals were taken against them, because, among other things, there was some feeling on the part of the governor that they had had just cause, and the rebellion simply petered out.

Other nations Akawaios

Of the other nations familiar to us nowadays, the Akawaios had a more extensive settlement pattern than they have today, being found in the Essequibo, Mazaruni, Cuyuni upper Demerara and upper Berbice. As mentioned above, they were enemies of the Caribs, the friction possibly arising because they lay across Carib trade routes. Since they had good relations with the Arawaks, the Dutch used the latter as peacemakers between the two whenever hostilities arose.

Some Akawaios lived behind the plantations in the Cuyuni and would hire themselves out as workers for special tasks. Like all the other nations dealing with the Dutch they provided all kinds of things, including salted manatee and parrots. In addition, of course, they grew and prepared annatto for the Dutch – it had to be made into little balls and set in crab oil to preserve it on the long journey to Amsterdam.

Warraus

The Warraus were the boatbuilders of the region, and lived on the swampy coastlands in houses on stilts. They probably disappeared from there after the planters began moving their cultivation downstream at the end of the Dutch period. But their main service was in providing salted fish for the government plantations. They had a fishery in the Orinoco which supplied the Essequibo plantations, and in the case of Berbice, they fished twice a year in the Canje. It represented an important cost saving for the authorities in both colonies.

Macushis and Wapishanas

The first contacts with Europeans the Machusis and Wapishanas would have made would have been with the Portuguese in Brazil. They encountered the Dutch only indirectly and at a late stage, after they began to filter into Guyana somewhere between the beginning and middle of the 18th century, crossing the river into the northern Rupununi savannah from Brazil.

At some later point, the Wapishanas started to migrate to the south savannah across the Kanuku Mountains, giving the arrangement which obtains today, with Macushis only in the north and Wapishanas alone in the south.

The reasons for the migrations are not altogether clear, but most likely relate to the need to find a more secure habitat away from powerful slave-raiding nations like the Manao and related tribes from the Rio Negro, and the Caripuna of the Rio Branco. Even in Guyana the two nations fortified their villages against attack.

During the last quarter of the 18th century the Portuguese started rounding up the tribes of the Rio Branco and forcing them into mission settlements. Serious uprisings in these settlements in the 1780s, in which the Brazilian branches of the Macushis and Wapishanas played leading roles, brought far more refugees into our Guyana. In fact, the word ‘Toshao’ which is employed now all over Guyana in place of ‘Captain’ was brought here by the two nations from the Portuguese missions. It is originally a Tupí word from the Amazon used in Lingua Geral, the language created by the missionaries there for use in their missions.

Arekunas

The Arekuna began most likely to appear in what is now Guyana after 1770. Spanish Capuchin missionaries were rounding up Arekuna far up the Caroní and Paragua Rivers in what is now Venezuela, and placing them in the missions on the Orinoco. Quite clearly, some sectors of the nation sought to avoid this fate by moving into the Dutch sphere.

Patamonas

Next to nothing is known of the Patamonas in the early Contact period at the present time. Nowadays they are domiciled in the Pakaraimas, and presumably they were there too when the Dutch arrived. They were certainly there at the beginning of the 19th century when William Hilhouse saw them and referred to them as the “mountaineers” among the Amerindians.

They are, of course, closely related to the Akawaios, speaking a language which is similar. The late Dr Desrey Fox, herself an Akawaio, said that tradition had it that the Akawaio were a breakaway segment of the Patamonas.

Wai-Wais

The Wai-Wais who live in the far south are the most recent of the Amerindian arrivals here, and would not have known the Dutch, although they might have encountered the odd Dutch trader in Brazil, their original domicile.

It is not absolutely clear when they arrived, although it seems to have been early in the 19th century, in addition to which nothing much is known about why they moved. It may have been connected to Portuguese pressure in the Rio Branco area, or pressure from another nation.

Spanish Arawaks

There is one special group living in Moruka who came as a consequence of the Venezuelan war of Independence in the early 19th century. They are known as the Spanish Arawaks, because they intermarried over the years with the Arawaks living in the area, but the original group had various tribal origins.

In 1817 the Catholic missions of the Orinoco were destroyed, and some of the inhabitants settled as refugees in Moruka. They were Roman Catholic of course, they spoke Spanish, and they eventually learned Arawak, the language of those among whom they lived.

The oldest generation to this day speaks both Spanish and Arawak as well as English. Their first interactions with the British authorities here were directed towards securing a priest to minister to their spiritual needs.