By Al Creighton

This is an edited version of three features which appeared in Sunday Stabroek on October 24, October 31 and November 7, 2010.

Among the most exciting developments in Guyanese art over the past quarter of a century has been the rise of Amerindian art. It is not that it had no real presence or recognition before that, it is more that certain factors drove it into prominence, and a number of important new directions in the artists’ preoccupations caused Amerindian art to come into its own and make a resounding impact over the last twenty years or so.

Looking back at the history of Amerindians and art in Guyana, one finds archival pieces; and several drawings, paintings and pictures of Amerindians in traditional settings, giving an impression of artists and travellers’ interest in romanticism, if not exoticism. Added to that is, of course, anthropological documentation. There is also prehistory, and the still physical presence of petroglyphs and rock paintings which, further to that, have been a major source of influence for the use of Amerindian motifs in modern art.

That was certainly strong in artists who were Amerindian, such as Stephanie Correia, who used them in ceramics and then explored mythical material in paintings. But the strongest explorer of these motifs was not Amerindian at all, but foremost Guyanese painter Aubrey Williams. Another of the most prominent Guyanese artists for decades before 1990 was Marjorie Broodhagen of Dutch and Amerindian ancestry who used motifs and created a famous tapestry owned by the University of Guyana, but who also had other wide interests. And then there was the rise of the distinctive features of Amerindian art which started in the 1980s.

There were important contributory factors to this rise. One of these had to be George Simon, whose work was already on the highest levels of national art by that time, but whose interests in mythology, spirituality and indigenous traditions deepened and even exploded after that period.

Another factor was the emergence of his brother Oswald Hussein, who rocketed to national prominence with the discovery of the sheer power, the excellence and uniqueness of his sculpture in the late 1980s. He made the greatest impact registered by any one individual and rocked the exhibition halls with startling pieces not seen before, winning the major prizes in the national exhibitions. The other major impact made by an individual was Winslow Craig’s arrival in the 1990s when he moved out of art school straight into the most hallowed corridors of national art because of his excellence and outstanding presence.

The single event responsible for the world really taking notice of Amerindian art as a major subject and its rise to its present power was the exhibition of six men identifying themselves as ‘Lokono Artists’ at the Venezuelan Cultural Centre in 1998. This was a group led by Simon out of St Cuthbert’s Mission that included Hussein, Linus Klenkian, Telford Taylor and Roaland Taylor. This group of sculptors and painters for the first time put on show in one place some of the most important characteristics of the art that had emerged. This work, much more than any other exhibition before it, was influenced by those ingredients and exhibited those factors that give meaning to Amerindian art. The Lokono are Arawaks and these artists showed the close relationships between them and their environment, between their environment and the art. It represented the spiritual beliefs, the closeness to nature in the spiritual presence in the things of nature, the forest, the birds and other animals; the mythology and the way men can transform themselves into forest animals and how spirits take the form of birds and other animals.

The show by Six Lokono Artists was the most important exhibition of Amerindian art up to that time and established the arrival of this brand of work and its prominent place in Guyanese art. There was first of all the identity. This was foregrounded by the men through the unmistakable ethnic identity in the exhibition’s title. That was taken a bit further in the choice of language, that is in the use of ‘Lokono’ rather than the better known name ‘Arawak.’ This communicated a greater depth of meaning made more significant by what was contained in the works themselves. That was the groundbreaking exhibition not because it was the first to put Amerindian art or the peculiar characteristics of it on show, but because of the statement that it made.

Of particular note is the way sculpture is used. Linus Klenkian has spoken about collecting wood for his art and gives meaning to the closeness between the medium and the forest in addition to the way the images that are created reflect the forest environment.

Wood carving influenced by the spiritual is well known among intuitive artists in Jamaica, and this was escalated into prominence by Malika Kapo Reynolds, for example, decades ago. Very intricate motifs are also one of the great hallmarks of Guyana’s Philip Moore, but more than in any other art in the Caribbean, there is a profound empathy in the tales told of the forest in Guyanese Amerindian sculpture. It is informed by the ethos, the cosmos, myth and spiritual beliefs.

Nature is not only trees, birds, and animals, but a oneness between these, the environment and the spirit of man. The animism and folklore recorded in the writings of Walter Roth find visual expression in the prevalence of mythical birds, bird-shapes and grotesque bird-like images in the sculpture. The same goes for animals such as serpents, jaguars, mythical and grotesque animal images. These abound because of the belief that given the learned skills, man can transform himself into these creatures and achieve empathy with the forest. Human spirits can take the form of animals.

This is important in hunting, in the skills of hunters and their beliefs. It is said that in some Amerindian nations when men go hunting they do not eat any of the meat from the game they bring home for fear that those animals might be the spirits of their own ancestors. (It is all right for them to eat from what others have killed.)

As was so fascinatingly fictionalised in Pauline Melville’s Ventriloquist’s Tale, hunters can learn to become one with the environment, to acquire the skills of ventriloquism and shape-shifting.

But dominating these particular beliefs is the presence of Kanaima. Mythology has it that Pia (who became the good medicine man – the piaiman) and Kanaima (who became the malevolent, cruel kanaima) were twin brothers, alter-egos who grew into opposites of each other and opposing human forces. However, many have emphasized that kanaima exists and he is not a myth, but a man. Just like the hunters, men can learn to be kanaima, take the shape of the jaguar, whistle like birds and hunt down their foes or prey. They are often assassins who pursue their victim relentlessly.

These personalities are frequently reflected in the sculpture as in ‘Shaman and his Medicine’ or in ‘Snake Walking Stick,’ both by Roaland Taylor, as well as in Valentine Stoll’s ‘Male and Female Deer,’ ‘We Are One’ or Arapaima by Oswald Hussein. Another pertinent form arising from this may be found in Telford Taylor’s totem poles and the much smaller totem pole ‘Good Spirit’ by Stoll. Hunters and kanaima find representation in ‘Hunter’s Visage’ by Winslow Craig, ‘Jaguar Attacking’ and ‘Native Hunter’ by Stoll.

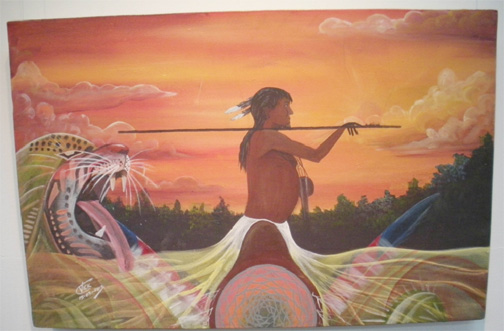

Among the painters there is much use of what George Simon calls “transformations,” which relate closely with both the protean kanaima and the various spiritual onenesses. His student from the University of Guyana, Anil Roberts, employs it in ‘Nature Love’ (2010). It appears to be a detail from the magnificent mural ‘Palace of the Peacock: Homage to Wilson Harris’ on the university campus. Roberts goes into nature, but depicts the oneness of man and the landscape in the way he merges the figure of a girl with a waterfall, a river, a lotus flower and an eagle, punctuated by petroglyphs. The body of a girl becomes the Kaieteur Falls in keeping with images from Harris’s novel in which a female figure appears clothed in the mist of the falls which transforms itself into an illusion of a woman wearing a garment made out of her own hair.

The leading sculptor Oswald Hussein is very much a living symbol of the art. A native of St Cuthbert’s village, he has achieved empathy with his environment and identifies himself with the forest and the landscape.

He feels that his spirit and the natural environment are one. He explains that long ago he had always wanted to be a jaguar or an eagle. For him the forest was a way of life and in order to create the art he wanted he had to discover himself. Nature is reflected in his work because it has become “the temple of [his] body” and his art is who he really is. He relates how he once saw wood floating in the water looking like a crocodile. He carved it and to him it was an invitation from the water spirit to sit on a live crocodile. This ‘crocodile’ experience inspired him to “explore ideas and forms and put life into an ordinary bit of wood”; but actually what he was doing was “seeing the life in it” and “bringing

that life out.”

Interestingly, although Oswald Hussein is not an intuitive artist, this kind of atavistic spirituality is what lies behind the striking force of his work. He was the first of the Amerindian sculptors to put spirits into the forest and animals, producing sculpture which is alive with the Arawak psyche. More than any of the others Hussein’s work startles with the fearful and the grotesque because of this close relationship he feels with the spirits of the forest. This personal conviction lends his work a defining quality of Amerindian art.

Hussein goes on to declare “I like thunder and lightning. I use nature as something that gives strength.” Before he could create those works depicting thunder and the house of the jaguar, “I had to find myself first. I believe in what I am doing.” He relates to the environment and “live[s] directly with nature. I feel I could turn into something.”

Unlike Hussein, Winslow Craig does not feel that personal closeness to his native environment, although he has never been divorced from it. He is indeed influenced by the environment. “I was born in the bush, grew up in the bush” and his work reflects his early life. But he is not immersed in mythology and legends, and feels that he uses them only superficially. What is more important to Craig is that his work “reflects all humanity.” His work “reflects all of who I am. I am a mixture, I am Amerindian, but my work does not reflect me as an Amerindian.”

That declaration is both borne out and not supported by Craig’s art. His ‘Strength of the

Harpy: Vision and Claw,’ ‘Hunter’s Visage’ and ‘Embrace’ are very much within the general Amerindian preoccupations. But for the most part those spiritual and traditional elements tend to give way to a certain universality. His style is more highly polished, more classical and much more realistic than Hussein’s. He seems to strive after a studied, dispassionate excellence. When he moves off into working in metal, a craft he developed in New Zealand, what is definitely reflected is his universal interest.

Yet an important factor in Craig is his preoccupation with social issues and the depiction of social realities, particularly his interest in “dark situations.” Artists, he believes, need to look at the realities that are placed before them. Craig’s importance then, is the high place he has earned in Guyanese art and his national achievements as a sculptor of Amerindian extraction.

As a kind of a balance between Craig and Hussein, yet much too important and far too accomplished to be looked at in that way, George Simon’s interests are as wide as the cultures of the world and as deep as his Amerindian identity. He has paid attention to his native background; he has researched Amerindian mythology and spirituality and at one time had a personal interest in shamanism, but has developed a serious interest in “the myths, religion and culture of others”. This is represented by his tendency of late to show mixtures and mergers in his paintings. For example, he paints the Haitian goddess Simbi in a Pakaraima savannah setting.

In his work during 2009 and 2010, he seems unable to confine himself to a single theme or a single culture in any one painting. In the ‘Homage to Wilson Harris’ that he produced together with colleague Philbert Gajadhar and student Anil Roberts, he enters an intertextual engagement with Harris’s novel. But the work is steeped in Amerindian motifs which are blended with details from the novel. One of the motifs is “eyes.” This is linked to the hawk or eagle eyes of kanaima, the eyes of the jaguar and the notion that the forest has eyes. There are several eyes in the peacock’s tail.

His preoccupation with the jaguar allows him to explore a very Amerindian subject because of that animal’s associations with kanaima, with the hinterland environment and with myth. His painting ‘Golden Jaguar Spirit’ (2010) sees the jaguar as “a shamanistic animal” with attributes of spirituality. The marks on the body of the jaguar are eyes, but they are also petroglyphs as well as the leaves of the forest. Here he alludes to the changing forms as from kanaima to animal, as well as the merging and the oneness among animal, forest, spirit and man.

He explores the female figure in his “transformations,” mixing cultures, religions and goddesses, moving among Voodu, Hinduism, African and Amerindian goddesses. Simon also has a keen interest in the serpent and its importance in his own culture, but also brings in the flying serpent-dragon of the Chinese, the mythical Mexican bird-serpent and the female energy in the camoudi from which the Caribs descended in one of the myths.

Simon is decidedly too original and innovative to be typical of anything, but he very eloquently demonstrates some of the most exciting developments in Guyanese Amerindian art. More than that, he is a leader in charting its directions.