Mark this for a mercy; that here

birds, even here, sustain

the wide and impossible highways

of warm current, divide the sky;

mark this- they all day have

amazed the air, that it falls apart

from their heavy wings in thin wedges

of sound; though the dull black earth

is very still, sweating

a special sourness

they make high over the hard thorn-trees

their own magnificent turning,

they chain all together

with very slow journeys to and fro

the limits of the dead place;

smelling anything old and no longer quick.

Even, here though the rough ground

offers no kindness to the eye

nor the rusting engines could not ever

have intended an excellence of motion

and the stones have fallen in strange attitudes

and the boxes full of dried stain papers

above the harsh barrows of land and metal

great birds pursue a vigilant silence

The ceremony of their soaring

have made a new and difficult solace

there is no dead place or dying so terrible

but weaves above it surely, breaking

the fragile air with beauty of its coming,

a comfort as of crows…

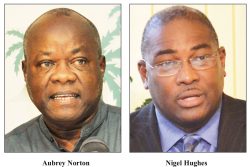

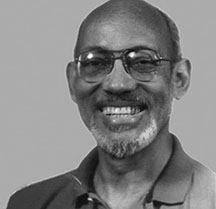

A poem like ‘A Comfort of Crows’ is not what Dennis Scott is best known for, yet it is not alien to those common characteristics of poetry and theatre that have made him one of the most outstanding poet-dramatists of the Caribbean. Dennis Scott (1939-1991) of Jamaica, is foremost in the region’s literature for the quality of his work, but also very importantly for its impact, because he has been one of its most influential dramatists and poets. Firstly, he was among that generation of poets that critic Edward Baugh identifies as giving a defining voice to Caribbean poetry at the end of the 1960s. After the achievements of Walcott and Brathwaite it was Scott along with Mervyn Morris, Anthony McNeill and Wayne Brown who Baugh referred to as registering the arrival of a confident and representative regional poetry arising in that generation.

Added to that was the shaping of his own distinctive voice and style which almost immediately became very influential. Both Scott and Morris are known for contributing the Creole voice and oral linguistic qualities to the poetry that developed in the early 1970s. One of the defining poems of this type is ‘Dreadwalk’ which uses not only the creole voice, but the linguistic qualities of ‘dread talk.’ At that time among the local elements that were helping to define the poetry were the Creole language, the oral qualities arising from both the spoken voice and the oral traditions, a rising African consciousness, a proletarian orientation, performance, the influence of reggae (dub) on poetry and the mainstream acceptance of Rastafari. These same factors led to the creation of Dub Poetry which started in Jamaica and developed in England led by Linton Kwesi Johnson. But outside of Dub Poetry itself, mainstream poets who worked in Standard English were very close to these developments and shaped their own verse using creole and Rasta voices creatively. Various personae in poems by Morris and Scott use dread talk, and this emerged from that time and that movement. But more than that, Scott and Morris became quite influential where the spread of these elements in West Indian poetry were concerned.

These same factors led to the creation of Dub Poetry which started in Jamaica and developed in England led by Linton Kwesi Johnson. But outside of Dub Poetry itself, mainstream poets who worked in Standard English were very close to these developments and shaped their own verse using creole and Rasta voices creatively. Various personae in poems by Morris and Scott use dread talk, and this emerged from that time and that movement. But more than that, Scott and Morris became quite influential where the spread of these elements in West Indian poetry were concerned.

One of the most definitive poems is ‘Uncle Time’ by Scott which translates Old Father Time into a Caribbean figure encompassing the passage of time itself, the erosion of the landscape, ageing, bitter experiences and a cunning Anansi figure.

Scott’s influence was also very strong in the theatre. He trained as a dancer, but developed more definitively as a playwright and director. The play ‘An Echo in the Bone’ (1974) is a powerful work whose post-modernistic style was particularly striking and innovative at the time, making an impact and setting a trend in the way theatre developed. Added to that was the way it used the form of the wake or the nine night as a tradition with spirit possession, visitations from the past and the purging of ills. ‘Dog’ (1977) was another in a similar form with as resounding an impact as ‘Echo in the Bone.’

Scott was also responsible for much of the development of the Jamaica School of Drama, which was the only institution of its kind in the Caribbean for several years and trained several of the region’s theatre practitioners. As a director, though, his work made its mark in other areas because he was a part of the rise of the professional theatre in the Caribbean as well. He worked with Trevor Rhone at the Barn Theatre and it was his direction of Smile Orange and School’s Out that drove the rise of a popular theatre of social realism and the theatre as a profession.

The impact of Scott’s work seems never ending when one considers the creation of famous Caribbean poems about birds, of which ‘A Comfort of Crows’ is one. But it is among the lesser known, since the poem ‘Bird’ has been so much more far reaching, a poem matched by Olive Senior’s ‘Birdshooting Season’ – both sensitive and ironic.

It might therefore be slightly off the map in the chronicles of Dennis Scott’s great achievements, except for its neatness, mystery and the sheer power of its quality. It is about carrion crows and may be reminiscent of AJ Seymour’s well known work, or even that of Wordsworth McAndrew. But it assumes a superior quality of its own with its mysteries and the atmosphere and setting it creates in which the crows (Jamaica’s jankro) circle, creating a beauty of black images against the sky. The poem gives a visual image of large groups of them etched against the bright sky – in the poem the way they “amaze the air” and “divide the sky.” They have “their own magnificence.”Yet, what is indeed typical of Scott, is the depth of these descriptions and the irony of these visual effects. There is a darker side. They hover over “a dead place” providing “a comfort” and “breaking / the fragile air with beauty.” Scott repeats the phrase “even here” in his description of unpleasant surroundings – it is not a cheerful or beautiful place. These are birds of carrion, associated with death and the ugliness of their appearance when seen close up. This place might be a garbage dump, a “la-basse” or a “dungle heap” that they frequent, or a cemetery. It is in such unsavory surroundings that the poet remarks how “even here” one could never have “intended an excellence of motion” or any idea of “comfort.”

The poem thrives on those ironies and the contrasting idea but the

co-existence of ceremonial dignified soaring and unpleasant images of squalor. The poem is full of metaphors and remarkable observations that cause the poet to remark and alert his audience to “mark this” (repeated) and “even here” (also repeated). There are conflicting images against a place that offers “no kindness to the eye.”

Those depths of thought and vision with an ironic approach, and that thoroughness of crafting, whether it be drama or poetry, are not alien to the work of Dennis Scott.