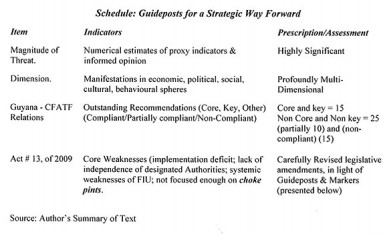

The Schedule below summarizes the key features of the strategic guideposts for a way forward presented in the two previous columns. These have been designed to address the current impasse facing Guyana and the Caribbean Financial Task Force (CFATF). Together they seek to contend with the legislative part of Guyana’s outstanding obligations the CFATF (and by extension the global Financial Action Task Force – FATF). These guideposts provide dynamic guidelines for not only resolving the immediate stalemate but hopefully also providing the basis for a strategy designed to reform anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism and proliferation into the medium-term and long-term.

As the Schedule indicates, these guideposts are rooted in the acknowledgement of 1) The considerable scope and scale of the money laundering threat in Guyana 2) The profoundly multi-dimensional nature of that threat, covering as it does political, economic, social, cultural and behavioural spheres of life 3) The tension, which exists between the government and the opposition following the former’s call for immediate action due to the perceived threat of external sanctions by the CFATF and FATF 4)The core weaknesses of the current money laundering legislation (Act 13 of 2009).

Following on these guideposts, I next provide some specific markers that I believe the Members of the Special Select Committee on Money Laundering should apply to the legislative amendments before them. The first set of these markers should focus on incentivizing the frontline regulatory/oversight bodies and others that are engaged in countering money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism and proliferation.

Marker 1: Earmarking Seized Assets for Frontline Bodies

Marker 1: Earmarking Seized Assets for Frontline Bodies

Key among the glaring weaknesses observed with the existing intelligence and enforcement authorities in Guyana are the limited resources they have to fulfil their functions. It is therefore, recommended that the Committee should consider in detail, and then apply, a legislative schedule for rewarding those bodies (and their personnel) with part of the proceeds of assets seized from money launderers and terrorist financiers. This will not only incentivize the frontline bodies, but it will help create a basis for the sustained financing of these bodies.

However, it should be made clear that this is a recommendation aimed at generating supplementary resources for the frontline agencies and personnel. It would be ill-advised to make them depend on this for their regular resources. It is vital for personnel of the regulatory and oversight regime to be principally motivated by their professional training and obligations to protect the rule of law and stamp out financial crimes.

However, it should be made clear that this is a recommendation aimed at generating supplementary resources for the frontline agencies and personnel. It would be ill-advised to make them depend on this for their regular resources. It is vital for personnel of the regulatory and oversight regime to be principally motivated by their professional training and obligations to protect the rule of law and stamp out financial crimes.

Marker 2: Earmarking Proceeds for the

General Public

The second marker directly follows on the first, and its rationale is basically the same. Members of the public or persons who “tip off” the Competent Authorities should be similarly incentivized out of the proceeds from seized assets. It goes without saying that for both Markers 1&2, legislative rules and not executive discretion should be the basis for rewarding those who fulfil their civic responsibilities in this regard. Legislation is preferred over executive discretion, since the rules governing the disposition of part of the proceeds from seized assets to those directly engaged in anti-money laundering, and combating terrorist financing should be law-governed, and not the product of executive fiat. This is recommended also to protect against abuse, which can readily occur if the process is not defined in law.

Marker 3: The Technology Gap

The second set of markers the Committee should keep in mind relates to the likelihood (for all sorts of reasons that directly or indirectly relate to available resources) of a widening gap in IT technology available to money launderers and financiers of terrorism and Guyana’s Competent Authorities. Worldwide this tension between the capacity of states and criminals generally plays a central role in determining criminal outcomes.

Criminals seek to harness innovation and ingenuity to their cause since they recognize that these attributes enhance their ability to game the Authorities. The Authorities therefore cannot risk falling behind and allow a significant technology gap to emerge. And, since the best general motivating force making for the availability of their skills is willingness to pay, the Authorities have to be in a position to recruit these skills for themselves. Here again the proceeds from assets seizure can help.

Marker 4: Cost of Compliance versus Non-Compliance

The general economic expectation is that those affected by regulatory regimes would, if they were rational, weigh the probabilistic cost of their compliance against the costs of their non-compliance. Committee Members therefore, need to weigh the outcome of this calculation as they proceed to approve legislation. The more definite are the penalties and costs of non-compliance, the more likely economic agents are to seek to comply; the risk-reward relation is not skewed in their favour. This therefore, means that as a general rule, the less ambiguous are the rules and regulations and also the more precise and certain are the penalties for non-compliance, the greater is the likelihood of compliance.

Next week I shall examine the remaining markers.