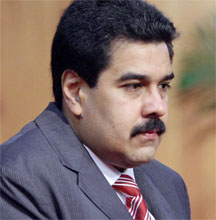

BUENOS AIRES — Beleaguered Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro may be able — or not — to remain in power for the remainder of his term, but Venezuela’s influence elsewhere in Latin America seems to be diminishing as rapidly as the country’ s dwindling foreign reserves.

Last weekend, the Venezuelan government lost a new potential ally in the region when leftist candidate Xiomara Castro — the wife of Venezuelan-backed deposed Honduran president Manuel Zelaya — came in a distant second in Honduras’ presidential elections.

According to official results, the right-of-centre president-elect, Juan Orlando Hernández, won by more than five percentage points. Castro disputed the results, but international observers ratified Hernández’s victory, and even Nicaragua’s President Daniel Ortega — one of Venezuela’s closest allies — congratulated Hernández for his victory.

Weeks earlier, in Argentina’s October 27 legislative elections, President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner — a populist who was very close to late Venezuelan strongman Hugo Chávez and is friendly with Maduro — failed to win a congressional super majority that would have allowed her to change the constitution and run for a third term in 2015.

Weeks earlier, in Argentina’s October 27 legislative elections, President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner — a populist who was very close to late Venezuelan strongman Hugo Chávez and is friendly with Maduro — failed to win a congressional super majority that would have allowed her to change the constitution and run for a third term in 2015.

Fernández returned from a month-long medical leave in late November with a videotaped message in which she appeared with a little dog named Simón, after Venezuelan independence hero Simón Bolivar, which she said was a present she had just received from Chávez’s brother Adán.

But aside from that symbolic gesture, Fernández’s financially-strapped populist government seems to have little hope of getting help from Venezuela as it did between 2005 and 2008.

On the contrary, after her electoral defeat, Fernández seems to be making a sharp turn to the right.

Last week, the Fernández government struck a deal to indemnify Spain’s oil giant Repsol, which it had expropriated in 2012 and threatened not to pay a cent. Argentina, which had triumphantly hailed the expropriation as a “recovery” of its national sovereignty, will now pay more than $5 billion for the takeover. In another political u-turn, Fernández is now speeding up negotiations with the Washington-based International Monetary Fund to repair Argentina’s damaged ties with international creditors.

In recent years, Fernández, much like Chávez, had regularly lashed out against the IMF.

While Fernández clings to her 1970s leftist rhetoric, the end of the boom in commodity prices that allowed her government to buy millions of votes with cash subsidies in recent years is forcing her to seek domestic and foreign investments. The most common phrase you hear in Buenos Aires’ political circles is, “Se acabó la fiesta” (The party is over).

In Central America and the Caribbean, Petrocaribe — the Venezuelan institution that provides subsidized oil to friendly countries — has raised from 50 per cent to 60 per cent the cash payments it demands from member countries and is also raising interest rates on their long-term oil debts. In early November, Guatemala announced its withdrawal from Petrocaribe, saying that the new payment conditions were no longer attractive.

“Over the past six months, the United States has surpassed Petrocaribe as the main supplier of fuels to Central American and Caribbean countries,” Jorge Piñon, an oil expert with the University of Texas at Austin, told me last week. “Things have changed very fast.”

Earlier this year, Venezuela lost another potential ally when right-of-centre Paraguayan President Horacio Cartes won that country’s presidential election.

Even some of Latin America’s best-known Chavista ideologues, such as German-born Mexican leftist Heinz Dieterich, who is credited with having coined Chávez’s term of ‘Socialism of the XXI Century,’ are distancing themselves from Maduro. Dieterich made headlines last month when he described Maduro as a “fraud.”

My opinion: You don’t have to be an enlightened political scientist to forecast a continued decline of Venezuela’s political and economic influence in Latin America. As hard as Chávez tried and now Maduro tries to disguise it with ideological slogans, their ‘Socialism of the XXI Century’ was nothing but an authoritarian populist vote-buying scheme that worked when Venezuela’s oil prices were at all-time highs. But oil prices have fallen, and Maduro has run out of money to keep giving away to win votes. Venezuela’s foreign reserves have plummeted from an all-time high of $42 billion in 2008 to $20 billion today.

The Venezuelan economy is in ruins, with inflation surpassing 50 per cent a year — one of the world’s highest rates — and growing food shortages. The Venezuelan fiesta is over, and you can feel the ripple effects with various degrees of intensity in much of Latin America.

© The Miami Herald, 2013. Distributed by Tribune Media Services.