Introduction

Many tend to believe, including yours truly, that if we can just chart a new constitution to promote some form of power sharing, establish the Public Procurement Commission, re-establish the Ombudsman, and similar good institutions the country could be on the path of economic certainty and national unity. However, we often tend to ignore the private sector’s performance as one of the key links in the chain of national unity. It is much more difficult to share and craft good laws if the economy is not growing; indeed, it is hard to share a stagnant pie or a shrinking roti among growing family members increasing in numbers. Bad economic outcomes and skewed income distribution strain social relations and increase the likelihood of conflict.

Moreover, public sector workers will be able to experience better salary growth if the private sector is productive and growing. The success of the entire country depends on the success of private businesses. In turn, private businesses have a social responsibility and not just one of maximizing profits as the American-British corporate governance framework dictates. The private sector can play a role in democratic consolidation, instead of being an instrument of the elected oligarchs.

A common feature of the Jagdeo Administration was the creation of a subservient private sector. The PPP under Jagdeo set out to engineer the “newly emerging private sector” (NEPS), some of whose members today appear to have coalesced under the umbrella of the Private Sector Commission (PSC) making this body very partisan . We should note, however, that the PSC is not the private sector. Those in the NEPS are favoured by the state and receive special concessions and privileges. The political elites, in turn, receive side payments or off-the-book payments (or rents to use the economist’s term). This does not augur well for national unity or long-term economic growth. Stifling non-conformist businesses implies productivity is not as high as it could be or some innovations are being thrown out the door.

Constraints facing private businesses

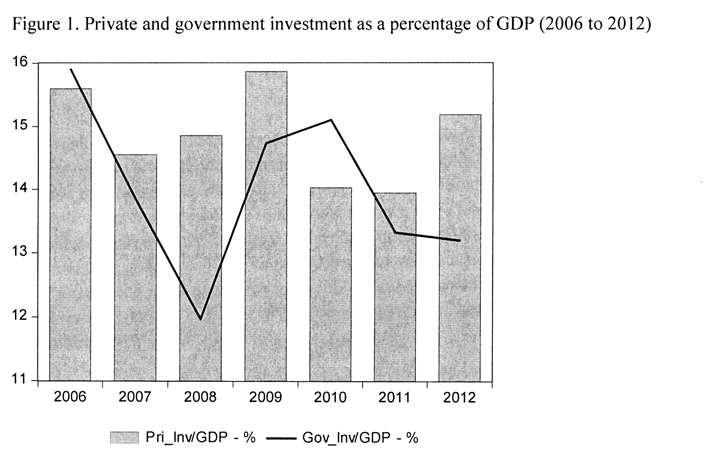

Private businesses already face numerous constraints. The political constraints merely increase the cost of doing business in Guyana, thus causing the private investments to stagnate (see chart below). In spite of the favours the NEPS receive, the World Bank ranks Guyana at 115 in cost of doing business out of a total of 189 economies for 2013. Some of the factors the World Bank measures when calculating the cost of doing business index are: (i) ease of obtaining construction permits; (ii) reliability of electricity; (iii) ease of getting credit; (iv) investor protection; (v) tax rates; (vi) ability to trade across borders; (vii) contract enforcement; and other factors.

Some might be tempted to conclude that the proposed Amaila project would have solved the problem of unreliable and high price electricity. This was far from certain, however. For starters the hydro volatility – fluctuations in the amount of electricity generated by the plant owing to changes in water flows – implies that GPL would still have to run diesel engines during the dry season. Therefore, Amaila would not have taken Guyana completely off of fossil fuel as some have argued. Second, serving as the intermediary between Sithe and the consumers, GPL would have had to spend millions of US$ to get its act together to pass on the fairly low wholesale electricity price to consumers. The feasibility study done by the Argentine consultancy also did not factor into the final price of electricity the need to continue running engines using bunker fuel.

Numerous other constraints are faced by private businesses; for example limited pool of human capital, lack of physical security, high cost of finance, credit rationing to new and non-traditional businesses, poor infrastructure like the lack of a deep water harbour, poor sequencing of key infrastructure (why a new airport terminal before a deep water harbour?), and others. Perhaps the greatest constraint private businesses face is the strategy of the political elites that involves controlling the business space. Private businesses seen as unsympathetic to the government are penalized; even the people’s tax monies would be used against the business to create unnecessary competition in an already small marketplace. For example, the people’s tax monies are used to set up the Marriott to compete with the Pegasus.

Stagnation of private investment

In a previous column – “Slow fiah, mo fiah and the Guyanese growth stagnation” (Aug 12, 2009) – I observed the private investment rate in Guyana. In that column we saw that the ratio of private investments to GDP declined almost monotonically from 1992 to 2008; thus the argument that the Hoyte protests scared away private investments is not supported by the evidence. Indeed, the data suggest that the rate of private investment relative to GDP started to decline since 1993 after reaching a peak in 1992. My thesis has always been that the decline of the private investment rate has to do with the barriers to entry the oligarchy erects as they seek to dominate the business space.

I will redo the chart in this column using data from 2006 to 2012. The reason for this is because the statistical authorities in Guyana rebased the GDP statistics from 2006 to capture new industries and changing structure of the economy. The new data set ought to be able to capture a more diverse structure of private investments. Before we continue, a digression relating to the rebasing of GDP is in order. Guyana’s per capita GDP is said to be around US$3000. This is mainly due to the rebasing that brought in previously ignored production activities into the official statistics. The compound and arithmetic rate of growth from 1992 to 2012 do not justify a per capita GDP of around US$3000.

Figure 1 updates my earlier chart from the “Slow fiah, mo fiah…” column using data from the 2012 Bank of Guyana Annual Report. The private investment rate is shown by the bar chart, while government investment rate is given by the line chart. It is clear that since 2006, after GDP was rebased, there is no clear trend in private investment, which tends to fluctuate around an average of 15%. In a sense, one can argue that private investments have stagnated around 15% of GDP.

A percentage of about 25% to GDP is necessary if growth is to speed up to about 7% annually. Not all private investments are made equally, however. The government might be tempted to use the easy way out by bringing in foreign investors to operate mainly in resource extraction industries, which often result in volatile growth mainly because commodity prices are determined in flexible price auction markets. Production activities based on natural resource extraction also tends to be susceptible to resource curse such as smuggling and side payments. It is not that Guyana should not exploit its natural resources. Indeed, such exploitation should be concomitant with a wider system of diversification focusing on tradable and non-tradable value added industries.

Government investments have fluctuated around an average of 14%. Government investments can be done much more smartly focusing on creating a tertiary education hub in Guyana (targeting Latin America and Asian students) and medical tourism as they are trying to accomplish with the specialty hospital. Investing in a Marriott is a complete waste of investment funds that could be better deployed by the private sector.

Comments: tkhemraj@ncf.edu