Take a boat up the Berbice River to where the Dutch once had their plantations, and it all seems so peaceful, quiet and sleepy. The dark waterway, snaking through bush and then savannah no longer echoes with the cries of the revolutionaries from 1763, but the shadows of the past still linger in the names of places now devoid of human habitation, but where once those in bondage reordered the sequence of the colonial story.

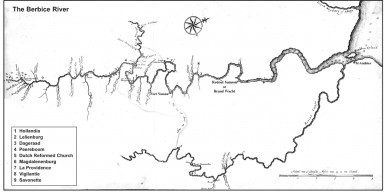

At the time that story begins, Berbice was a relatively small colony owned by a private company known as the Berbice Society (Soceiteit van Berbice), often referred to as the Berbice Company in English. Not only did it own the colony, but it also owned a few large plantations as well, some of which grew sugar. Two of these – Peereboom and Dageraad – were to play a prominent part in the rising. The company also controlled some military installations on the Berbice River, the main one being their headquarters at Fort Nassau, about 56 miles upstream, that consisted of a brick redoubt protected by wooden palisading, whose boards had become quite rotten by the time of the rising. The others were a small fortification called St Andries, near the mouth of the Canje approximately where the Fort Canje Hospital now stands, and the Brandwagt, which was a signal station some miles up named Redoubt Samson.

Most of the plantations in both Berbice and Canje were privately owned, and there were quite a lot of them. It would be misleading to suggest, however, that this was a wealthy colony; far from it. There was little capital available to Berbice planters to invest in their estates, and while land grants were large by the standards of the West Indian islands, not much of that land was under cultivation as a general rule. Anyone who visualises Coffy (Kofi, Cuffy) and his fellow revolutionaries wielding cutlasses to cut cane, therefore, has got it wrong; they worked on plantations with a more modest capital investment which grew cotton, coffee and cacao (cocoa) in some combination or the other.

Furthermore, the numbers of enslaved on each estate were small. Not for Berbice the averages of 200 or 250 which were to be found on plantations of the period in Suriname and Jamaica; averages on the maybe 100 or so private Berbice plantations were in the region of 34, although the figures on the Berbice Society estates were much higher than this, as a consequence of which about one third of the total enslaved in the colony could be accounted for on their plantations or at their military installations. By and large, the enslaved Africans and Creoles with a few Amerindians who laboured on the Society’s plantations, were not enthusiastic recruits to Coffy’s cause; the same does not appear to be true, however, of those attached to Fort Nassau and the military fortifications.

Given the above, it is hardly surprising that the total population of the colony, including the enslaved (both African and Amerindian) and whites, was very small – less than 4,000 in fact. There was no great concentration of people anywhere in Berbice because there was no concentration of plantations; these were strung out singly on both sides of the river for miles upstream, and the main means of communication between them was by boat. While there were paths across the savanna in the dry season linking Berbice and Canje, there were no roads in the colony as such, and the main highway was the river itself. It was not, in short, a geographical layout which lent itself to the actions of rebellious slaves.

All those forced to endure slavery longed for freedom, but taking up arms on any scale against the planters and the military was an extremely hazardous exercise with a very low success rate indeed, while the consequences of failure were grim. The revolutionaries of 1763 gave their main reason for rising up, the cruelty of certain planters whom they named; there is also one reference to a shortage of rations. Whether planter cruelty on the plantations had increased beyond its previously brutal norms prior to the uprising, will probably never be known, but there was indeed a shortage of rations. Whether these conditions persuaded a larger number of people than would usually be the case to take the risk of trying to gain freedom through open revolt, is impossible to say.

However, there were other factors which potential rebels pondering their options would have taken into account in assessing their chances. For the first time external conditions were operating in their favour, opening at least the possibility of success.

Epidemic, anxiety

First there was the epidemic sweeping the colony which affected the whites and the free Amerindians most – although many of the latter moved out of Berbice to escape it. The Africans were least affected by it, suggesting that it was something to which they already had some immunity – yellow fever, perhaps, although we will never be sure. Whatever it was, it reduced white numbers significantly, either through sickness or death, and as a consequence the Governor of Berbice, Wolfert Simon van Hoogenheim, could not muster more than a few soldiers of the garrison in a crisis. It was a god-given opportunity for those of a revolutionary bent.

Secondly, as mentioned above, many of the bush Amerindians moved out of the colony because of the epidemic, and since they were sometimes called upon to discharge a custodial function in relation to the plantations, their absence opened up new possibilities for would-be rebels.

Thirdly, the whites revealed their psychological weakness by their panicky attitude, whereby they circulated rumours about rebellions all around Berbice; until the real thing came along in February 1763, none of these rumours was found to have any substance. Their physical weakness too was put on public display when in 1762, the authorities took an inordinately long time to deal with a small maroon encampment high up the river consisting of a group which had run away from one of the upper river plantations.

And then, on 23rd February, 1763, the slaves on Magdalenenburg in Canje rebelled. Traditionally, this has always been cited as marking the beginning of the Great Uprising. However, that was probably not the true beginning but rather the prelude to the main event. That news about it spread like wildfire around the colony there can be no doubt, although whether that had any effect on the revolutionaries who were plotting action themselves on the Berbice River will possibly never be known.

Outbreak

Those who made the Great Uprising of 1763, came from a group of mostly contiguous plantations along a specific stretch in the middle of the settled stretch of the Berbice River, called Head Division, and from there the revolt spread downriver, and later upstream and into the Canje River as well.

The details we have about the conspiracy at the moment are limited, but the rising seems to have started prematurely, and even Coffy said in a letter he was angry that they started. Premature or not, the timing turned out to be serendipitous. The date was the 27th February, and the day was a Sunday, when most of the planters of the area were upriver attending to their devotions in the Dutch Reformed Church near the Wiruni Creek. After the service, they no doubt went carousing, because it was not until evening that they returned home.

It was the rebels on Plantation Hollandia who appear to have begun the action because they feared their conspiracy had been betrayed, and after that they went to the plantation next door – Lelienburg – to collect Coffy, the man they had chosen as leader, and his deputy, Accara. According to one source, Coffy and Accara smeared themselves with white clay and then broke open the chests and cupboards where the firearms and ammunition were stored. After that, they went back to Lelienburg and broke open the chests and cupboards there.

News about the uprising was spread by the talking drums, and by the time that Burgher-Captain Van Lentzing, who was in charge of the Head Division militia, came cruising down past the revolutionary plantations in his tentboat, all he could see were flames around him, and all he could hear was the sound of shouting and smashing against a background of relentless drumming.

Valour was not Van Lentzing’s strong suit, and along with fellow members of the militia from the area, he soon scuttled downriver to the safety of Fort Nassau on the excuse of collecting reinforcements. Van Hoogenheim was not pleased to see him, and always thought his cowardice in refusing to stand and fight when the revolutionaries could still have been contained in the middle section of the river had allowed the uprising to become general.

Guided by the Amerindians, the planters high up the river who were above the revolutionary plantations eventually escaped through the bush to Demerara, but those closer to the Wiruni Creek took refuge in a house belonging to the Berbice Company on a plantation called Peereboom. They managed to get word to Van Hoogenheim that they were there, and while he didn’t have any soldiers he could send, he commandeered one of the four ships anchored at the fort waiting to be loaded with produce, and ordered its captain to go to the relief of the planters in Pereboom. The skipper of this vessel – a Captain Kock – had other ideas, and allowed himself to be detained by two Councillors of Government in front of their plantations, while they loaded his boat not just with produce, but also furniture and all their other belongings.

Battle of Peereboom

While all this was going on, the first battle of the uprising took place at Peereboom. The Dutch were under the command of Burgher-Captain George, who was in charge of the upper river, and the revolutionaries were led by Cossael − who probably had the rank of Lieutenant − a Congo from the plantation of Oosterleek. While the house itself was of brick, the roof was made of thatch, and the revolutionaries succeeded in setting it on fire by firing nails bound around with burning cloth. However it was extinguished by the women and children with buckets of water. By the end of the day, Dutch ammunition was low and water was running out, and since no help had arrived from Fort Nassau, they listened to Cossael when he addressed them during a lull in the fighting. Given their situation, George agreed to negotiations.

According to the agreement made by George and Cossael, the whites were to go down to their boats the following morning and row straight to Fort Nassau without stopping on the way. However, on the morning of March 3rd, as the Dutch were picking their way down the slope to the river, the revolutionaries opened fire on them. Many were shot dead, although a few escaped by jumping into the river while the remainder were taken prisoner.

A few of the prisoners were set free; one of these was Mrs Schreuder whose late husband had worked on a Company plantation, and who was released because it was said she had always been kind to the enslaved. There was also Pastor Ramring and his family, who was freed because when he was asked whether when he prayed to God he prayed for the enslaved as well, responded that he prayed for all people. Several of the prisoners were executed, the nature of their deaths reflecting how cruel they themselves had been. Some women and children were sent to work in the fields, while George’s eldest daughter became Coffy’s wife, and her little sister served as her maid. There was no other occasion during the rising when the Dutch were killed in any number.

Retreat

In the meantime there was panic at the Fort, with planters and their families crowding in for safety, and later hiding on the boats moored at the stelling because they thought them less vulnerable than the fort. They passed the time by peddling endless rumours about the revolutionaries being about to attack them. After Van Hoogenheim’s military officers advised him that if the cannon were fired three times in succession, the palisading would collapse, the governor decided the fort should be abandoned and then set on fire. This was done on 8th March, and the fleeing Dutch floated downriver, eventually to the very extremity of their colony, at Fort St Andries, near the mouth of the Canje.

Here all was misery, with the planters and some officials clamouring to go home to the Netherlands, the epidemic raging, no proper security and fresh water having to be brought in from up the Canje every day. The numbers in St Andries were swollen by the Canje planters who had fled there too when they heard that Fort Nassau had been abandoned. However, just when things seemed as though they could not get any worse for the Dutch, on 28th March, deliverance arrived in the form of a brigantine carrying 94 soldiers sent by the Governor of Suriname.

This changed the military odds, because Van Hoogenheim wasted no time in sailing back upriver to the Society plantation of Dageraad which was much more easily defended than St Andries, and entrenched himself there. Everyone who wanted to leave the colony was given a pass to do so, and only those who were prepared to stay and fight remained – which, it must be said, was very few. Coffy and the revolutionaries had missed their first and best option to give their uprising a more permanent character, by failing to dislodge the Dutch when they were at their weakest.

In the meantime, Coffy, who had first made his base on Hollandia, and then moved in to the buildings around Fort Nassau as soon as the Dutch evacuated it, had been drilling his soldiers, organising the spread of the revolt, rounding up firearms and ammunition, and generally trying to deal with the administrative problems attendant on finding himself in charge of such a large body of people. In particular, of course, he had to ensure they could be fed. At a fairly early stage, he opened a correspondence with Van Hoogenheim, and the latter responded with a view to buying the Dutch time.

Battles of Dageraad

The Dutch were barely ensconced on Dageraad, when on 2nd April, Coffy’s army commander Accara, launched an attack at seven in the morning. After two-and-a-half hours the revolutionaries withdrew, and attacked again at one o’clock in the afternoon, but the assault was a failure. Coffy himself was apparently upriver at the time, and was not pleased that the attack had gone ahead.

Despite this, matters were not going well at Dageraad, where among other things, the sickness was still taking its toll, but the Dutch mood was buoyed by the unexpected appearance of two boats from the island of St Eustatius with 154 men on board.

The revolutionaries too had their problems, especially a shortage of gunpowder for ammunition, which is why Coffy may have been angry with Accara for wasting it on the battle of April 2nd. Reading from the sequence of events, it seems as though Coffy decided on one major battle to root the Dutch out, and according to Ineke Velzing, his plan was to capture one of the large ships moored in front of the plantation that were equipped with cannon. This would certainly have helped give him control of the river, but although his troops fought well, he did not achieve his objective.

The Second Battle of Dageraad began around 10 o’clock in the morning on 13th May, and ended around 2.30 pm. The cannon Coffy had wanted to capture fired on his forces, and in the end they had to retreat.

As long as things were going well, Coffy could probably assert his authority without too much difficulty, but after the defeat of May 13th, the canker of disunity made itself manifest. The first split was between the Africans and the Creoles, and at one point the arguments got so acrimonious that the Creoles threatened to kill Coffy. Eventually, he

managed to persuade the groups to patch up their differences, but it was a sign of worse to come.

Corentyne, Canje

In the meantime, the Magdalenenburgers who had run away to the Corentyne after they revolted on the 23rd February, found themselves fighting the Caribs there. Governor Crommelin of Suriname had also sent soldiers after them, and the second group he dispatched fighting in conjunction with the Caribs almost wiped them out. Following that battle, however, 41 of the Suriname soldiers who were mercenaries and mostly of French and German nationality, mutinied after a quarrel with their superior officer over spoils.

To the utter amazement of the revolutionaries in Canje, who were under the command of Fortuijn of Helvetia and Accara of the Brandwagt (not the same Accara as Coffy’s army chief), the deserters presented themselves as defectors from the Dutch who were willing to help the cause.

Not surprisingly, the sceptical Canje forces simply did not believe them, and promptly shot 28 of them. The remainder, however, were rescued by an officer sent by Coffy and taken to Fort Nassau. There they worked for the revolutionaries repairing firearms and training the army. At a later stage in the revolt Atta used them too, and two of them also led his forces in battle on at least one occasion.

If the revolutionaries up to this point had been less than successful in the main river (Peereboom excepted), Canje was one theatre of operations which was a success story. On 6th April they had won a battle against the Dutch at Fredericksburg, and on 23rd July, they drove the Dutch from their last remaining post low down the Canje River at Wijborg.

Coffy’s death

Things in the upper Berbice, in contrast, were not so rosy. Caribs sent by Governor Storm van ’s Gravesande of Essequibo to fight with the Dutch arrived in Berbice and attacked the revolutionaries in Savonette, the highest plantation on the river, inflicting losses. Coffy was suitably alarmed, and dispatched Accara his army commander to take charge of the situation. The Caribs had been issued with firearms by the Essequibo governor, and were not short of ammunition, and Accara was not successful in dealing with them.

Coffy had other problems too. Food was short, ammunition was short, and his own authority was under challenge. What was clear was that there was no unified vision of aims and strategy; Coffy was seeking to set up something akin to a state, and proposed to Van Hoogenheim the division of Berbice into two halves, the lower half going to the Dutch, while the revolutionaries would keep the upper half. Not everyone perhaps, was so enamoured of that vision, and the Africans in particular probably had less grandiose plans.

In any event, the issues coalesced around Coffy’s correspondence with Van Hoogenheim, and Atta, who had only arrived in Berbice the year before the rising broke out, confronted him directly on it. After a meeting of army officers during which both leaders asked for support for their positions, there was dissension between the two groups, following which Coffy committed suicide. It must be inferred from this, (the account comes from Accabré at the end of the Uprising) that Coffy found he could not command enough support in the army, which is why he committed suicide.

One account says that before he died Coffy buried the gunpowder still under his control, but whether or not that is so, the revolutionaries honoured him with the burial of a great chief and killed two whites on his grave. No one knows where he is buried.

Atta

Following Coffy’s death there was a very brief interlude when an old man called Boi was made Governor-in-Chief, and Atta and others became governors. He was unable to exert control over the revolutionaries, however, and dismayed by what he regarded as the excesses committed by some of them, he retired to his plantation.

It was at this point that Atta took over the leadership. Atta’s period of governorship, however, was marked by particular dissension between the Africans in the colony. These were loosely organized into four nations, representing the different parts of Africa from which they had come. Atta was a Delmina (the name derives from the fact that he would have been shipped through the port of Elmina), and most likely belonged to one of the Akan tribes. Then there were the Congos and the Angolans or Loangos. The fourth nation was represented by the Guangos, who were clearly a very small grouping indeed, and whom Monica Schuler has suggested were Imbangala – a kind of renegade tribe − from the Kwango River in Congo.

At this stage there was no unified vision or long-term objective such as the one Coffy had tried to promote, and there was little co-ordination between the groups. Eventually relations between Atta and the other nations deteriorated, until finally, towards the end of November or in early December the Delminas and the Congos met each other in battle on the plantation of Essendam, led by Atta on the one side and Cossael on the other. Cossael is not heard about again, so perhaps he was killed in this battle, but it is known that Coffy’s former field commander, Accara of Lelienburg, was. Afterwards, his body was taken upriver, and he was given the burial of a great chief.

One must infer that Atta effectively won the Battle of Essendam, because he now turned his attention to the Angolans, his Delminas killing any groups of them who were encountered in the bush.

What Atta did not do, however, was organize food supplies, and very soon all these were exhausted; all the cattle roaming on the savannah had been killed, and every horse – including Van Hoogenheim’s – had ended in the cooking pot. In a situation of near starvation, it was the turn of cats and dogs, but there eventually came a point when for many of the revolutionaries there was nothing accessible to eat. In the midst of these trials, the Dutch began to receive reinforcements from the Netherlands itself.

Dutch troops

The first contingent arrived on 28th October, 1763, and Van Hoogenheim sent them up the Canje River to close off avenues of escape to the east. His plan was to hold off driving up the Berbice River itself until the Essequibo Caribs had thrown a net around the upper colony, so the revolutionaries would not be able to melt into the bush and set up little maroon camps everywhere. When the Dutch appeared in the Canje, Fortuijn who was the governor there, and his army commander, Accara of the Brandwagt, were told by Atta to abandon the river and come to Berbice but to burn everything before they left. This they did. It must be said that owing to the acute food shortage, the Berbice revolutionaries were not that happy to see Fortuijn and his people.

But worse was to come. Further reinforcements arrived for Van Hoogenheim sent by the Directors of the Berbice Society on 27th November, while on 19th December, a substantial force sent by the States-General (the Dutch parliament) made its appearance in the river.

Van Hoogenheim now felt confident enough to start a drive up the Berbice River proper, and it was at this point that Atta came into his own, fighting a dogged guerilla campaign in the Wikki Creek. In one encounter against him, the Dutch through arrogance and carelessness lost all their officers in charge of the action – albeit not very senior ones − and although they eventually won, it was at best a pyrrhic victory. Hungry and plagued by dysentery, Atta’s forces fought bravely and with determination.

The above-mentioned troops sent by the States-General were only the advance guard; on 1st January 1764, the largest expeditionary force ever to set sail for a Dutch colony announced its arrival in the Berbice. It comprised 660 volunteers from various regiments, which after this came to form the nucleus of the Dutch marine corps and which was later sent to fight the Bonni maroons in Suriname. At this point, there was no possibility of retrieving the situation, and after further dissension and quarrels with officers like Fortuijn, the revolutionary troops scattered.

Traitors

Atta’s final blow came in an insidious form, when two leaders, Accara of the Brandwagt and Goussari, presented themselves at the headquarters of Colonel De Salve, the officer in charge of the state troops, offering to bring in leaders like Atta in exchange for a pardon, in addition to persuading the rank and file to come in. De Salve agreed, and the two were as good as their word. They were indeed subsequently pardoned, and for their own safety were taken out of the colony to the Netherlands, where they served as drummers in De Salve’s regiment. They were sent to Suriname with the new marine corps in 1772, and while there, Accara met his real-life brother working on a plantation.

There was one other operation the Dutch carried out, and that was against the Accabré’s maroon camp consisting of about 200 people, behind the plantation of Markeij. Accabré was accused by other revolutionaries of being a cannibal, and most of them were afraid of him and what they believed to be his powers. At an early stage in the uprising he was brought to Fort Nassau, and Coffy had wanted him killed, but Atta had intervened to save him. At the end of the rising the Dutch wiped out his camp, and when he was interviewed by Van Hoogenheim, the latter was impressed by him, recording that he was handsome and had the bearing of a prince. Accabré taunted and laughed at Atta when he was brought in, because he tried to kiss the Dutch governor’s feet.

Dutch revenge

Dutch revenge was terrible. After perfunctory hearings, or interrogatories, which also doubled as trials, a large number of revolutionaries were punished, many of them by death. The leaders had to endure the most horrendous forms of execution, which all of them, including Atta, bore with great courage and stoicism. Alarmed by the number of executions, Van Hoogenheim tried to put a stop to them with little success, and was eventually forced to write to the Directors asking them to issue on amnesty, which arrived on 15th December, 1764. The Company also freed sixteen of their enslaved who had served loyally with the Dutch throughout the period of the Uprising.