Last week we offered an analysis of Christmas as a religious festival, observing that it has also evolved as many other types and that its contemporary existence as a commercial and popular festival overwhelmingly dominates the religious function.

It was also observed that it is the most popular and most widely observed festival in the world, transcending boundaries of culture, religion and politics. An excellent example of this Beijing and the large urban centres of China which in many places look and sound like any Western city with the atmosphere, music and decorations, including Christmas trees, peaking on Christmas Day, which is a major and very special day for shopping and merchandising.

The focus narrows down this week to Christmas as traditional and cultural, analysing its close and historical associations with theatre.

The first connection has to do with the characteristics of traditional festivals of this nature. Those traditions that are religious (and Christmas started out as one of these) are of two types: those that tend to be exclusive or private and those with public outreach. The private and exclusive types reserve their rituals and performances for their own believers, devotees and celebrants and do not have public exhibitions. The second group (to which Christmas belongs) have both private and public practices, very often with the open exhibitions being a kind of public outreach which broadcast principles of the faith and sometimes messages.

The first connection has to do with the characteristics of traditional festivals of this nature. Those traditions that are religious (and Christmas started out as one of these) are of two types: those that tend to be exclusive or private and those with public outreach. The private and exclusive types reserve their rituals and performances for their own believers, devotees and celebrants and do not have public exhibitions. The second group (to which Christmas belongs) have both private and public practices, very often with the open exhibitions being a kind of public outreach which broadcast principles of the faith and sometimes messages.

Both of these use theatre or the theatrical. Ritual performances express spiritual belief and are traditional ways of expressing these or communicating them. Many of them are performed, using theatre or theatrical elements – sacred rituals are performed among themselves, while the outreach consists of larger public displays which express the belief in many ways including the use of myth, symbols, literature, stories, music and drama.

Christmas, we observed last week, has the largest and most multi-faceted public outreach of all. This has given rise to its own mythology and folklore, most of which is secular. But the public outreach of Christmas contains many of the spiritual beliefs, religious principles and messages of the festival expressed in various forms of theatre. These include much that is symbolically represented and dramatised. The tradition of giving gifts is a good example of symbol and dramatisation – in the original story the Magi brought gifts for a king; Christ coming to earth was a divine gift to mankind; gifts represent expressions of goodwill, reflecting the spirit of the season. These are all forms in which the principles are dramatised.

The grandest form of dramatisation of these principles is to be found in the secular and popular mythology already mentioned. At the centre of this is Santa Claus, a benevolent, generous, cheerful character who distributes gifts to children. He embodies the spirit of the season and the tradition of gift-giving which remains central to the religious/spiritual belief of the Christians (Christ as God’s gift to mankind/Christ sacrificing himself to give the gift of life to mankind). So that some of the popular, secular folklore still reflects the message of the religious outreach.

However, theatre is a part of it in more obvious ways. In Mediaeval times the practice of wassailing developed, its name coming from Middle English and meaning “good health.” The idea was drinking to wish each other good health. While Christmas is characterised by bouts of drinking and merrymaking, groups of revellers would go around the community from house to house performing Christmas carols and receiving gifts of food and drink. House-to-house performances emerged and were called mumming, in which groups of amateurs put on a small dramatic performance when they called at households. These were pantomime-like improvised playlets with the performers disguised in costume. They were similarly rewarded with refreshments at each place. This tradition continued well into the twentieth century and is documented in Thomas Hardy’s novel The Return of the Native.

As a traditional festival Christmas developed different traditions in different countries which have long since made the festival their own – thus it is a national festival in innumerable nations. Many European practices were imported and adapted, including the mumming tradition in the Caribbean. There are remnants of a masquerade performance known in St Kitts called the mummies, in which masked masqueraders travel around the village, stopping to perform at places. Stories of ancient battles and rivalries dating back to the Middle Ages and Shakespeare are included in the dramas recited and performed. While the Caribbean performance has no reflection of Christmas, it was traditionally performed at Christmas time as a form derived and imported from England and its Christmas time mummeries.

There are other forms of theatre in the Caribbean with relevant derivation. The performance of Papa Jab or Flavier the White Devil is no longer seen in St Lucia, but it is another masquerade performed on the streets in Castries at Christmas time while it existed, at least up to the 1940s or ’50s. The costumed folk masqueraders would act out the story of Flavier, an ageing devil whose rebellious sons bring him grief by fighting among themselves and eventually killing each other. Flavier forgives them and uses his power to revive them back to life in a typical masquerade doctor play. Apart from the timing of its performance (Christmas time) this street theatre reflected a message of forgiveness, peace, goodwill and rebirth which corresponds to the spirit of Christmas.

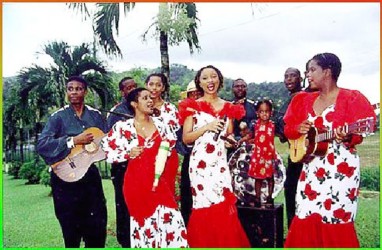

There is only one Caribbean folk traditional performance of this nature that actually carries the specific Christmas story. That is the Parang of Trinidad and Tobago which is still very vibrant. Traditionally, bands of performers would go “mumming” from house to house on Christmas morning singing Parang songs in Spanish to entertain the householders and be offered drinks and food. There are different roots to this tradition, but it carries with it the theatre of mumming, and of wassailing – the performance is singing, not pantomime. Yet, unlike all the other Christmas time traditions in the Caribbean the songs are about the Nativity and in praise of the Virgin Mary. This tradition also contains a brand of songs called aguenaldos, which are related to the giving of gifts, quite in keeping with the Christmas philosophy.

Another form of English Christmas theatre is the pantomime. It sprung from a folk tradition and is related to the theatre of Harlequin and of travelling troubadours in Spain, Portugal, France and Italy. In England it appears at Christmas and performs fairy stories or legends or romances. There are stock characters in every drama, though playing a different character in the different stories – some have males playing female roles and vice versa. The male romantic lead is played by a female and the Dame, a female comic character, is played by a man. This form was also brought to the Caribbean and developed considerably in Jamaica. There is now a Jamaica Pantomime which opens every year on Boxing Day and is a localised, transformed version. Its subject does not reflect the Christmas season in any way, but it is the continuation of yet another form of theatre related to the season.

Christmas has also been associated with theatre historically. The great theologian St Augustine (354-430 ad) while expressing a love for the theatre, was also very critical of it and found it and the response of its audiences, quite illogical and disfavourable (see his work Confessions). He was also quite happy with the decline of the theatre in the fifth century ad because he found it immoral. However, centuries later, ironically, it was right in the Roman Catholic Church that theatre had its great rebirth in Mediaeval times. It was the priests who began to write verses and dramas taken from the bible as a part of the mas to educate parishioners who could not read about the scriptures. Prominent among these were the Liturgical dramas about the birth of Christ. These grew into nativity plays dramatising the story, and this tradition continues today.

When nativity plays are not being performed there are tableaux in the cathedrals called ‘cribs’ with members of the dramatis personae associated with Jesus’ birth – Mary, Joseph, the Magi, the baby, the shepherds and the animals in the manger. These also appear as widespread Christmas decorations everywhere.

These Christmas plays grew too big for the altar and moved into the churchyard, then out into the towns, taken over by the people. So that, in addition to the founding of Christmas dramas, the Catholic priests gave rebirth to theatre itself, because public and secular theatre developed greatly from the religious dramas. There were also shepherds’ plays performed out in villages, so called because they started with shepherds as characters talking about the nativity.

Today is actually the eleventh day of Christmas and this evening will be the Eve of Twelfth Night, according to Old English tradition. Twelfth Night is January 6 at the end of the ‘12 days of Christmas,’ the Yuletide season which actually does not begin until December 25, Christmas Day itself. This is celebrated in theatre, a play by the greatest playwright of all time, William Shakespeare. Shakespeare wrote the comedy Twelfth Night in 1598, thus immortalising the Feast of Epiphany (12th night), beginning with the festive mood of the Season as Orsino the Duke commands:

If music be the food of love, play on

Give me excess of it; that, surfeiting,

The appetite may sicken, and so die.

That strain again – it had a dying fall.

O, it came o’er my ear, like the sweet sound

That breathes upon a bank of violets . . .