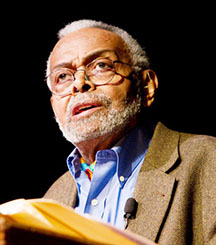

(New York Times) – Amiri Baraka , a poet and playwright of pulsating rage, whose long illumination of the black experience in America was called incandescent in some quarters and incendiary in others, died on Thursday in Newark. He was 79.

His death, at Beth Israel Medical Center, was confirmed by his son Ras Baraka, a member of the Newark Municipal Council. He did not specify a cause but said that Baraka had been hospitalized since December 21.

Baraka was famous as one of the major forces in the Black Arts movement of the 1960s and ’70s, which sought to duplicate in fiction, poetry, drama and other mediums the aims of the black power movement in the political arena.

Among his best-known works are the poetry collections “The Dead Lecturer” and “Transbluesency: The Selected Poetry of Amiri Baraka/LeRoi Jones, 1961-1995”; the play Dutchman and “Blues People: Negro Music in White America,” a highly regarded historical survey.

Baraka, whose work was widely anthologized and who was heard often on the lecture circuit, was also long famous as a political firebrand. Here, too, critical opinion was divided: He was described variously as an indomitable champion of the disenfranchised, particularly in the racially charged political landscape of Newark, where he lived most of his life, or as a gadfly whose finest hour had come and gone by the end of the 1960s.

In the series of alternating embraces and repudiations that would become an ideological hallmark, Baraka spent his early career as a beatnik, his middle years as a black nationalist and his later ones as a Marxist. His shifting stance was seen as either an accurate mirror of the changing times or an accurate barometer of his own quicksilver mien.

He came to renewed, unfavourable attention in 2002, when a poem he wrote about the September 11 attacks, which contained lines widely seen as anti-Semitic, touched off a firestorm that resulted in the elimination of his post as New Jersey’s poet laureate.

Over six decades, Baraka’s writings — his work also included essays and music criticism — were periodically accused of being anti-Semitic, misogynist, homophobic, racist, isolationist and dangerously militant.

But his champions and detractors agreed that at his finest he was a powerful voice on the printed page, a riveting orator in person and an enduring presence on the international literary scene whom — whether one loved or hated him — it was seldom possible to ignore.

“Love is an evil word,” Baraka, writing as LeRoi Jones, the name by which he was first known professionally, said in an early poem, “In Memory of Radio.” It continues:

Turn it backwards/see, see what I mean?

An evol word. & besides

who understands it?

I certainly wouldn’t like to go out on that kind of limb.

Saturday mornings we listened to Red Lantern & his undersea folk.

At 11, Let’s Pretend/& we did/& I, the poet, still do. Thank God!

Among reviewers, there was no firm consensus on Baraka’s literary merit, and the mercurial nature of his work seems to guarantee that there can never be.

Writing in the Daily News of New York in 2002, Stanley Crouch described Baraka’s work since the late 1960s as “an incoherent mix of racism, anti-Semitism, homophobia, black nationalism, anarchy and ad hominem attacks relying on comic book and horror film characters and images that he has used over and over and over.”

In contrast, the critic Arnold Rampersad placed Baraka in the pantheon of genre-changing African-American writers that includes Langston Hughes, James Baldwin, Richard Wright and Zora Neale Hurston.

Everett Leroy Jones was born in Newark on October 7, 1934. His father, Coyette, was a postal supervisor; his mother, the former Anna Russ, was a social worker. Growing up, young Leroy, as he was known, took piano, drum and trumpet lessons — a background that would inform his later work as a jazz writer — and also studied drawing and painting.

After studying briefly at Rutgers University in Newark, he entered Howard University. During this period, partly in homage to the African-American journalist Roi Ottley (1906-60), he changed the spelling of his name to LeRoi, with the emphasis on the second syllable.

Though by all accounts a brilliant student, he came to regard the university’s emphasis on upward mobility for blacks as distastefully assimilationist — “an employment agency” where “they teach you to pretend to be white,” he later called it. Losing interest in his classes, he was expelled before graduating.

He joined the Air Force.

“It was the worst period of my life,” Baraka told Essence magazine in 1985. “I finally found out what it was like to be disconnected from family and friends. I found out what it was like to be under the direct jurisdiction of people who hated black people. I had never known that directly.”

To stave off loneliness and misery, he read widely and deeply, stocking the library on his base in Puerto Rico with books — philosophy, literary fiction, left-wing history — the likes of which it had almost certainly never seen.

After three years, he was dishonorably discharged: Some of his reading material had made the Air Force suspect that he was a Communist. The irony, he later said, was that he did become a Communist, but not until long afterward.

He moved to New York, where he took an editorial job on a music magazine, The Record Changer, and settled in Greenwich Village amid the heady atmosphere of the Beat poets.

He befriended their dean, Allen Ginsberg, to whom, in the puckish spirit of the times, he had written a letter on toilet paper reading, “Are you for real?” (“I’m for real, but I’m tired of being Allen Ginsberg,” came the reply, on what, its recipient would note with amusement, was “a better piece of toilet paper.”)

In 1958 LeRoi Jones married a colleague, Hettie Cohen. Together they founded a literary magazine, Yugen, which published his work and that of Mr. Ginsberg, Gregory Corso and Jack Kerouac. With the poet Diane di Prima, he established and edited another literary magazine, The Floating Bear.

He also started a small publishing company, Totem Press, which in 1961 issued his first collection of verse, “Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note.” In the volume’s title poem, he wrote:

Nobody sings anymore.

And then last night, I tiptoed up

To my daughter’s room and heard her

Talking to someone, and when I opened

The door, there was no one there …

Only she on her knees, peeking into

Her own clasped hands.

His early poems were praised for their lyricism and for the immediacy of their language — throughout his career, he said, he wrote as much for the ear as for the eye.

Jones considered himself a largely apolitical writer at first: Like that of many Beats, his poetry was concerned more with introspection. But he was radicalized by travelling to Cuba in 1960, the year after Fidel Castro came to power, to attend an international conference featuring writers from an array of third world countries.

As a result, he later said, he came to believe that art and politics should be indissolubly linked.

His political awakening was soon manifest in his work. His first major book, Blues People, published in 1963, placed black music, from blues to free jazz, in a wider sociohistorical context.

Writing in The New York Times Book Review, the folklorist Vance Randolph said, “The book is full of fascinating anecdotes, many of them concerned with social and economic matters,” going on to commend its “personal warmth.”

Jones came to even greater prominence in 1964, when his one-act play Dutchman opened Off Broadway at the Cherry Lane Theater in the Village.

Experimental, allegorical and unabashedly angry, Dutchman was set aboard a New York City subway train. There, Lula, a young white woman, strikes up a conversation with Clay, a young middle-class black man. As the play unspools, she goads him, with apparent liberal righteousness, into releasing the anger that, as a black man, he must surely be harbouring.

When Clay finally explodes, Lula stabs him to death as other riders passively look on. After disposing of his body with casual impunity, she sits back, smiles and, as another black man boards the train, makes pointed eye contact with him before the curtain falls.

Dutchman won the Obie Award, presented by The Village Voice to honour Off and Off Off Broadway productions, as the best American play of 1964.

Jones’s other early plays include The Slave, a violent, futuristic fable about an American race war, and J-E-L-L-O, a farcical reworking of Jack Benny’s television show in which Mr. Benny and his friends are assaulted and robbed by Rochester, his newly militant black valet.

For all the acclaim that followed Dutchman, Jones largely disdained his newfound celebrity, turning down the scriptwriting offers that poured in from Hollywood. (A film version of Dutchman, with a screenplay by Baraka and starring Shirley Knight and Al Freeman Jr, was released in 1967.)

He turned instead to academia, teaching at Columbia, Yale and elsewhere. At his death he was emeritus professor of Africana studies at Stony Brook University on Long Island, where he had taught since 1979.

Jones was further radicalized by the assassination of Malcolm X in 1965. Soon afterward, having come to believe that marriage to a white woman was ideologically untenable, he left his wife and their two daughters and moved to Harlem. (In 1990 his former wife would publish How I Became Hettie Jones, a memoir of their time together.)

In Harlem, Jones founded the Black Arts Repertory Theater, which staged many of his plays, and an associated theatre school.

By the late 60s, after the theatre and school had folded, he had moved back to Newark, converted to Islam and adopted the Bantuized Arabic name Imamu (“spiritual leader”) Ameer (“prince”) Baraka (“blessed”), which he would later alter to Amiri Baraka.

Some critics felt that Baraka’s work from then on was the worse for his radicalism. In his 1970 essay collection “With Eye and Ear,” the poet and critic Kenneth Rexroth wrote that Baraka “has succumbed to the temptation to become a professional Race Man of the most irresponsible sort,” adding, “His loss to literature is more serious than any literary casualty of the Second War.”

By Baraka’s own later acknowledgment, his writings from this period contained elements of unvarnished anti-Semitism. In “For Tom Postell, Dead Black Poet,” published in his book Black Magic: Collected Poetry, 1961-1967, Baraka wrote: “Smile, jew. Dance, jew. Tell me you love me, jew,” continuing: “I got the extermination blues, jewboys. I got the hitler syndrome figured.”

In 1980 Baraka, who had by then renounced black nationalism as exclusionary and become, in his words, a “Marxist-Leninist-Maoist,” repudiated those views in an essay in The Village Voice titled “Confessions of a Former Anti-Semite.”

But the issue came sharply to the fore again in 2002. That September, shortly after he was appointed the New Jersey poet laureate, Baraka gave a public reading of “Somebody Blew Up America,” a poem he had written in the wake of the September 11 attacks. In it, he suggested that Israel had prior knowledge of the attacks:

Who knew the World Trade Center was gonna get bombed

Who told 4000 Israeli workers at the Twin Towers

To stay home that day

Why did Sharon stay away?

Baraka was roundly criticized, and New Jersey’s governor, James E. McGreevey, called on him to step down. He declined.

In 2003, after it was determined that the state Constitution had no provision for firing the poet laureate, the New Jersey General Assembly voted to abolish the position outright.

Baraka sued. In 2007, the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit ruled that New Jersey officials were immune from his suit; later that year, the United States Supreme Court declined to review the case.

That court battle echoed Baraka’s periodic brushes with the law throughout his adult life. In 1967, he was found guilty of illegal weapons possession during the racially charged Newark riots that year; he later won a new trial, at which he was acquitted.

After divorcing his first wife, Baraka married Sylvia Robinson, a poet later known as Amina Baraka. In 1979, during an altercation with her in New York, Baraka was arrested and charged with assault and resisting arrest. Sentenced to 48 weekends in a halfway house, he used the time to work on a memoir, The Autobiography of LeRoi Jones, published in 1984.

Baraka’s pugnacity was again in the news in 1990, when Rutgers, where he also taught, denied him tenure in its English department. In a widely reported public statement, he indicted unnamed members of the department as “Klansmen” and “Nazis.”

His ire over the years was scarcely reserved for whites. Calling them “backward,” he castigated a series of black mayors in Newark, where he continued to live, for what he saw as overly accommodationist policies, starting with Kenneth A. Gibson, the city’s first, who took office in 1970, and extending to Cory A. Booker, who held the office until he became a United States senator in October.

Baraka’s life was marked by great loss. In 1984 his sister, Sondra Lee Jones, who called herself Kimako Baraka, was stabbed to death in her New York apartment. In 2003 Shani Baraka, his daughter with his second wife, was shot to death in Piscataway, NJ, along with her partner, Rayshon Holmes.

James Coleman, also known as Ibn El-Amin Pasha, the estranged husband of Shani’s half-sister, Wanda Wilson, was convicted of murdering Shani and Holmes.

In addition to his wife and his son Ras, survivors include three other sons, Obalaji, Amiri Jr and Ahi; four daughters, Dominique DiPrima, Lisa Jones Brown, Kellie Jones and Maria Jones; and several grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Among Baraka’s many honours are the PEN/Faulkner Award, the Rockefeller Foundation Award for Drama and membership in the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He was seen in a small role as a homeless sage in Warren Beatty’s 1998 political satire, Bulworth.

Despite a half-century of accusations that he was a polarizing figure, Baraka described himself as an optimist, albeit one of a very particular sort.

“I’d say I’m a revolutionary optimist,” he told Newsday in 1990. “I believe that the good guys — the people — are going to win.”