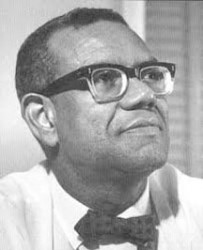

Today is the 100th birthday of Guyanese poet and man of letters, Arthur James Seymour (January 12, 1914-December 25, 1989). It is undoubtedly an important occasion and there is great cause for celebration of his life and work.

Significantly, Edward Baugh begins and ends his account of West Indian Poetry 1900-1970 with AJ Seymour. Although many things have happened in the poetry since 1970, Baugh’s work is not dated, and remains one of the most important critical works capturing the development and the decolonisation of Caribbean poetry. That Seymour occupies so much space in it confirms his recognition and underlines the acknowledgement of his place in the region’s literature.

Yet AJ Seymour is not a major writer. He is a minor Caribbean poet and was never regarded as among  the first flight of Guyanese poets. So why is he so important? Why does he occupy such a prominent place in Guyanese and West Indian literature?

the first flight of Guyanese poets. So why is he so important? Why does he occupy such a prominent place in Guyanese and West Indian literature?

He is among the most distinguished personalities in Guyanese culture and literature, and his importance to the regional poetry arises from his contextual place in the history of its development in the first half and the middle years of the twentieth century. Although the poems he produced are critical parts of that history, the weight of his recognition comes from a significant contribution as an editor, anthologist, commentator, administrator and cultural worker, and for the little magazine Kyk-Over-Al.

A J Seymour was extraordinarily prolific, causing Ian McDonald to remark that he was so preoccupied with several other things it was surprising that he managed to produce poems at all, let along write some 500 of them (AJ Seymour, Collected Poems 1937-1989 (2000)). This is certainly reflected in Joan Christiani’s AJS – A Bibliography (1974) which attempts to list all of his writings and activities over 40 years. Although not completely comprehensive or entirely accurate, it is a formidable volume of painstaking work which gives an excellent reflection of Seymour’s prolificity. Documentation is there of the wide range and extent of that author’s work. It shows that apart from poetry, he also wrote short stories and two plays. Volumes of articles, introductions and contributions to other publications are recorded.

But the biography of AJS will not be attempted here. That is adequately covered in helpful documents like Christiani’s, and in more devoted biographical accounts by Petamber Persaud in various articles, McDonald and Jacqueline de Weever in Collected Poems, Petamber Persaud’s Introduction to Guyanese Literature, and in A Goodly Heritage, the autobiography of Elma Seymour (Bryce) (1987). The last named is as much an account of the life of the wife of AJS as it is the life of the poet himself, in addition to being a documentation of the good middle-class life, the values and heritage of an old Georgetown that was disappearing. Elma Seymour took the opportunity to represent herself as not a mere limb of her famous husband, but the holder of an independent identity, if not career. She joined with AJ in editing a few volumes of poetry anthologies.

Arthur Seymour began his poetic career in 1937 with his first collection Verse (1937). He remarks that in the colonial setting of that time, he was looked down on as something of an “upstart” for daring to publish collections of poetry as a local native – having the audacity to aspire to what only people in foreign lands could do (Seymour in Edgar Mittelholzer: the Man and His Work, 1968). Actually, several volumes had already preceded his since 1900 in the Caribbean, and Egbert Martin, under the pseudonym Leo, had already started modern Guyanese literature with his collections in the 1890s. Yet, one of Seymour’s claims to a prominent place in history is that he was among a group of poets who were still pioneers of a sort in the 1930s. It was a thoroughly colonial climate and a period of imitation that characterised the Caribbean poetry of the early twentieth century. To write verse that could stand by itself at that time gave one a place in the real growth of West Indian poetry.

Seymour bridged that period that moved from the imitation of Victorian and Romantic English verse, when local poets either copied the landscape and culture wholesale or simply substituted local names for foreign things. He began writing at the time when Guianese poetry was beginning to find its voice and identity. By the 1950s the poets had taken on a more meaningful national presence. It was the dawn of a long period of a poetry of nationalism in pre-Independence British Guianese literature. Similarly across the Caribbean a gradual shedding of colonial verse and an awakening of national poetry had followed the industrial struggles and the emergence of self-government of the 1940s.

However, by far his greatest contribution that earned him a memorable place in the region was his editorship of the little magazine Kyk-Over-Al, 1945-1961. Around that time other journals were making similar contributions, such as Bim started by Frank Collymore in Barbados, Focus in Jamaica, and The Beacon in Trinidad (the last two doing more for fiction, rather than poetry). Added to the contribution of Caribbean Voices at the BBC in London, these helped in the making of West Indian literature. Kyk-Over-Al provided a rare opportunity for publication and an outlet for new and emerging writers. It also offered articles, commentaries, reviews and critical writing which would be a companion for the rising literature while helping to shape it. Although Kyk ceased publication in 1961, it was revived by Ian McDonald in 1984 and resumed its service to regional poetry.

It was through Kyk that Seymour made his other truly significant contribution to Guyanese literature. This was the publication of the most significant anthology of that era – An Anthology of Guianese Poetry (1954) which was published as a special volume of Kyk-Over-Al. Two previous anthologies of poetry are relevant here: Guianese Poetry 1831-1931 edited by Norman E Cameron in 1931 and An Anthology of Poetry by Guianese East Indians edited by CEJ Ramcharitar Lalla in 1934. Each of these was valuable for different reasons. Cameron produced a much needed and historically vital document of 100 years of the poetry, including the extraordinary Leo and the ordinary Francis Williams whose unremarkable sonnet commemorates Emancipation in 1838. It was work that needed to be done, as was Ramcharitar Lalla’s attention to what was not covered by Cameron. Except for one poem by Lalla himself, none of the work was memorable or free of imitation.

Seymour’s timely anthology in 1954 avoided the limitations of both its predecessors. It included a few of the poets found in both of them while giving a good view of what had developed since the 1930s. It recorded the state of Guianese verse at that time, including the newly emerging poets and the first glimpse of the nationalistic poetry that was on the rise. Some of the writers included were members of the P.E.N. Club that was starting to make its mark, and of the groups that used to meet occasionally to read and discuss poetry sanctified by the libation of plenty rum. (see mention of this by Mittelholzer and by David de Caires).

Another significant contribution by AJS showed post-Independence poetry of both Guyana and the Caribbean. This was the anthology New Writing in the Caribbean (1971) which was closely associated with the first Carifesta held in Guyana in 1972. The publication was, however, a product of plans made by writers at the two conferences of artists hosted by the Guyana government in 1966 and again in 1970. Seymour was very much involved and went on to coordinate writing in Carifesta itself. Andrew Salkey took detailed notes of the proceedings of the meetings and their plans for Carifesta, (see Georgetown Journal (1971) which included the compilation of a volume reflecting the poetry of participating countries for Carifesta. It was a policy of this that non-anglophone countries should be included.

As a member of the Department of Culture as it was then, Seymour presented the first Edgar Mittelholzer Lecture in 1967, producing a work that still stands as important today – ‘Edgar Mittelholzer: The Man and His Work’ (1968). There is also a series done on radio for the UCWI Extra Mural Department on Caribbean Literature (1951) which contains some of his comments on regional literature.

While Ian McDonald describes Seymour as a major poet, other critics do not place him so high on the scale of writers. Edward Baugh attributes his importance more to his role as a facilitator and contributor to the development of the literature. Even McDonald’s rating is accompanied by context and qualification. Baugh values the poems in a historical context and remarks, “In his own poetry we find him purposefully digging about in Guyanese history and legend, asserting continuities, going back to the Amerindians in the search for a Guyanese spirit. But with him history is really not much more than romance; he values the facts of history mainly for their romantic possibilities.” For Baugh, Seymour’s most famous poem ‘There Runs A Dream’ is a prime example of this.

But largely prompted by random remarks of Mark McWatt and from a re-reading of McDonald and de Weever’s edition of Collected Poems, one is surprised by the discovery of more and more strong poems in the poet’s repertoire. The Amerindian legends such as ‘Amalivaca’ and the ‘Legend of Kaieteur’ do seem to support Baugh’s estimation, although they are important to Guyanese poetry. By committing Amerindian mythology and legends to verse they make quite a contribution to Amerindian literature in Guyana. They also highlight the heroism which is truly a part of the Amerindian culture as seen in the very mythology. They do highlight the noble heroic ideals. An appropriate example is in ‘The Legend of Kaieteur.’ There are versions of the story of Kaie, the old leader of his people who gave the mighty Kaieteur Falls its name. Some of these versions are disappointingly trivial in plot and bereft of depth of meaning. Seymour chose the most noble of them to put to verse, thus immortalizing a heroic deed, although it must be said that is version does not correspond to the original legend as recorded by Barrington Brown, who first heard it from the Patamona.

Among Seymour selections that can stand with the best is ‘Carrion Crows,’ which is close to a line taken by Dennis Scott in ‘A Comfort of Crows.’ The poem turns on the contrasting images of carrion and beauty.

Yes I have seen them perched on paling posts –

Brooding with evil eyes upon the road,

Their black wings hooded – [. . .]

But I have seen them emperors of the sky,

Balancing gracefully in the wind’s drive [. . .]

And winnowing the air like beauty come alive.

He is even capable of eroticism as in ‘Love Poem I and II,’ going beyond the familiar Seymour in describing the seductive sexuality of female thighs, the caressing “in the hollow of the back” and “the inner thighs”; the “accelerating of desire” watching “shapely girls walk by.” He ties this to a theme of the dangerous and fatal attraction of these temptations subject to mutability and luring on to destruction – here he produces his most erotic of all “in the ballet of love . . . the blind worm butting to its doom.” This is surprising and atypical Seymour, but not surprisingly he blunts it by self-conscious references to the fact that he really shouldn’t be writing this “unmentionable in polite society.”

In some 50 years of writing poetry Seymour produced several collections including More Poems (1940); Over Guiana, Clouds (1944); Sun’s In My Blood (1946); Selected Poems (1965); I, Anancy (1971); Mirror (1975) and The shape of the Crystal (1977). He has his share of memorable lines, as in ‘Amalivaca’:

Seven days now this womb of sacred waters

Has made its marriage with oblivion

Over the sounding cliff of rock and i

Amalivaca in this tiny wedge

Driven between the witness centuries,

Have drowned my mind within the moving flood,

Married my human to watery particles

Searching the smoothness secret of its power.

There is an ideal Kaieteur of souls

Forever falling finally to death

Dropping their colour, shape and their lost form

From height of time into eternity.

These are some of the best lines from AJ Seymour, whose work McWatt laments “seems sadly forgotten these days.” But minor poet or not, it is lines like these that re-read in the poet’s 100th year, that will ensure his work is never forgotten.